Art. 121 of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea

Discuss the interpretation of Art. 121 of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea after the decision in PCA-Case N° 2013-19, Philippines vs China. Are there general conclusions to be drawn which can assist in other similar disputes around the world?

Siderakos Panourgias

Introduction

On the 22nd of January 2013, the Republic of Philippines commenced, under Annex VII to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an arbitration procedure against the People’s Republic of China. The dispute concerned the South China Sea and is mainly known as the South China Sea Arbitration (PCA case number 2013-19). The arbitration was made before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA). The Republic of Philippines claimed the violation of the UNCLOS Convention as long as historic rights, the source of maritime entitlements, the status of certain maritime features in the South China Sea were concerned and also doubted the lawfulness of specific actions by the Republic of China in the specific area. In particular, China’s rights were disputed over specific islands (island formations within the “nine-dash line”). However, China denied to accept the arbitration and did not participate in the whole procedure as it did not recognize the jurisdiction of the PCA in the specific case.

Area of Interest

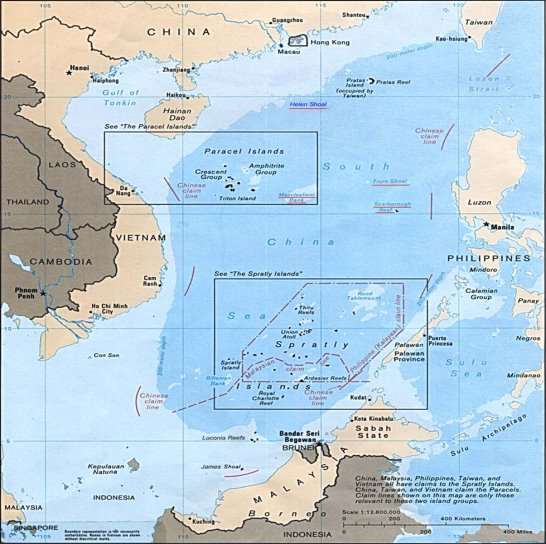

The South China Sea is a sea in the west Pacific Ocean and covers an approximate area of 3.5 million km². From north, it is surrounded by the mainland of China, Taiwan and Vietnam, from west there is Philippines, Malaysia and Sumatra and from south there is Borneo. Within this sea there are island and reef formations, from which the most important are the Paracel Islands, the Spratly Islands, Pratas, the Natuna Islands and Scarborough Shoal (fig. 1). The wider area of the South China Sea is very unique and interesting because annually, approximately one third of the global maritime traffic goes through these waters. The fishing stocks of the area are massive. Moreover, Japan and South Korea rely mainly on the South China Sea for their fuel and material supply and their trading, too. It is also believed by scientists that underneath the seabed, it contains huge reserves of natural gas and oil. In addition, the South China Sea is the area which contains highly considerable, reef ecosystems of high biodiversity importance. All the factors mentioned above have obviously transformed the South China Sea into a very conflicting area with essential, economic and geostrategic benefits for decades now.

Main Historical Background

The general dispute over the South China Sea has begun many years ago, from the decade of 1940’s after the WWII. More specific, in 1947 the Republic of China (Taiwan) published a map of the South China Sea with an eleven-dash line area, which included many island formations that claimed to be under its sovereignty. Two of the dashes at the Gulf of Tonkin were later removed in 1949, when the Communist Party of China took over the mainland of China, forming the famous “nine-dash line area” in the South China Sea (Wu Shicun, 2013).

In 1951, Japan renounced all claims to the Spartly Islands of the Republic of China (Taiwan). As a result, the Chinese government proceeded to a specific declaration, reestablishing China’s sovereignty over the wider area of the South China Sea, including the Spratly Islands.

The , from their side, based their claim for the sovereignty over the Spartly Islands to the geographical proximity.

Over the years, many events escalated the dispute. One of these was in 1956 when the President of the Philippines, Tomas Cloma and a group of his people, settled on the islands, even stole the national flag of China from the Taiping Island, and declared the islands as a protectorate of the Philippines with the name of “Freedomland”. A couple of months later he returned China’s flag to the Chinese embassy in Manila and wrote a letter apologizing and claiming that he would not proceed to any similar actions in the future. In the 1970s, some countries began to invade and occupy islands and reefs in the Spratly Islands.

The (PRC) from its side claimed that it was entitled to the Paracel and Spratly Islands because they were seen as integral parts of the . The took control of the (the largest one in the island formation) since 1946.

claimed that the islands have belonged to it since the 17th century, using historical documents of ownership as evidence. began to occupy the westernmost islands during this period. In the early 1970s, joined the dispute by claiming the islands nearest to it. also extended its and claimed .

Discussion

The dispute, as mentioned in the introduction, begun in 2013 when Philippines started a tribunal arbitration with the PRC, complaining about the legality of specific actions in the South China Sea, the legal basis of maritime rights and entitlements in the specific region and the status of certain geographic features. The basis, on which this arbitration and all its results must stand, is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Philippines accused PRC that the historical rights over the Spratly Islands had no serious evidence, it was responsible for artificial-constructed islands that ruined the natural environment and also for the over-exploitation of the South China Sea from Chinese fishermen under its permission and tolerance.

UNCLOS

The UNCLOS is a convention that was signed in 1982. Both the Philippines and the PRC are members of it, having it ratified in May 1984 and June 1996, respectively. The most basic and essential aim of this Convention was the desire of the States Parties “to settle, in a spirit of mutual understanding and cooperation, all issues relating to the law of the sea and aware of the historic significance of this Convention as an important contribution to the maintenance of peace, justice and progress for all peoples of the world” (UNCLOS).

The Convention was ratified by the number of 168 States. In its articles, a very wide range of issues are being analyzed. A small listing of them includes territorial and internal waters, transit and innocent passage of ships, to Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), Continental Shelf and sovereignty on resources. More specifically, it provides the coastal States the framework in order to establish the zones and their limits, in which they exercise their national jurisdiction. Moreover, in the Convention, a specific organization is authorized in order to resolve peacefully any dispute that will arise between States in the future. This organization is the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA).

The PCA was the organization that Philippines asked for its tribunal arbitration in the case of the South China Sea, using the Annex VII of the Convention. The most relevant, with our case, zones are the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the Continental Shelf, the High Seas and the Area.

However, the PCA was not responsible and of course could not address the sovereignty over land territories, in particular over the Spratly Islands or the Scarborough Shoal. A matter that was clearly stated in the South China Sea Arbitration Award of 12 July 2016.

Article 121 Interpretation

In this report, the article that has more importance is the article 121. According to the UNCLOS, the article 121 states that:

“  1. An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.

2. Except as provided for in paragraph 3, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of an island are determined in accordance with the provisions of this Convention applicable to other land territory.

3. Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.”

The three paragraphs of the article 121 mentioned exactly as in the Convention above, play a major role in the arrangement of the jurisdictions and sovereignties all over the world, as long as there are waters and islands in them. Firstly, paragraph 1 states with great clearance the definition of the island. A “naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water…” automatically excludes everything that is artificially created. No artificial-constructed islands can be considered as natural. As a result, artificial islands cannot have any maritime zones around them (contiguous zone, EEZ, continental shelf etc.). The only zone that they can legally have is a safety zone that cannot extend to more than 500 meters from its outer edges. The purposes of this safety zone are completely for maritime safety reasons. Moreover, if an artificial island can be officially proved to be a maritime danger according to the international maritime safety standards due to abandoning or misuse, it will be completely removed on its whole. (unclos article 60)

Secondly, in paragraph 2 it is clearly stated that natural-formed islands have all the legal maritime zones around them as all other land territories do. A very strong statement, that designates many rights but also obligations to the sovereign State as long as the maritime zones are concerned and all their characteristics.

Thirdly, paragraph 3 gives the most important statement from the whole article. That is that any small island (rock) with no human habitation or economic life can have no EEZ. A statement that is both clear and logical, because having a small island with an oil platform, a casino or a military base on it, does not automatically make it a real island with an Exclusive Economic Zone. The human habitation could not be supported by its own powers and the economic life cannot be developed on a social basis. If a fact like this could be legal, that would extend the jurisdiction and sovereignty of the owning State 200 nautical miles even further into the ocean, interfering with other coastal States’ rights and jurisdictions.

China’s interpretation over Article 121

It was inevitable that China’s interpretation over the article 121 would raise many objections from its side. The most important matter for China, that it referred to many times officially, was the Japanese Oki-no-Tori-shima rock. “Oki-no-Tori-shima is an atoll, located in the western Pacific Ocean between Okinawa and the Northern Mariana Islands, of which only two small portions naturally protrude above water at high tide.”(Award)

Under that definition, and following directly the directions of the Article 121 (3), China denied the existence of continental shelf of the Oki-no-Tori-shima rock as it cannot sustain human habitation or economic life on its own. A rock that is currently under Japanese sovereignty and jurisdiction. A general acceptance of the non-existence of the continental shelf of the current rock, would automatically reduce the Japanese rights in the specific area by two hundred nautical miles. A huge area with many benefits, both social and economic, as it affects both the local life of people fishing in this area but also the exploitation of possible deposits in the seabed. A possibility, supported by many scientists and theories, which could easily bring in enormous amounts of profits to the owning State.

Furthermore, China claims sovereignty both on the Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoal. Its actions imply that China considers Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Dao in Chinese) as a fully entitled island, naturally formed and with all the following maritime zones around it. Such actions (e.g. the banning of fishing north of 12° North latitude and the objection in petroleum surveys and concessions in the area) specifically signifies China’s thoughts and considerations over the Scarborough Island in the wider area and its rights and jurisdictions on it.

Tribunal’s decisions

The CPA reached adjudication, mainly rejecting any claims of China in the South China Sea by “historic title”. Furthermore, in accordance to Article 121, the CPA did not recognize the Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal as naturally formed islands. Therefore, these low-tide elevations cannot generate maritime zones around them. Also, it declared that Subi Reef, Gaven Reef (South), Hughes Reef, Scarborough Shoal, Gaven Reef (North), McKennan Reef, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef are not islands that can sustain human habitation or economic life, so they do not have the right of any maritime zone. Finally, it declared that the Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are within the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of the Philippines.

In general, as seen above, the CPA did not recognize any sovereign rights or jurisdictions of China related to the “nine-dash line” area, claiming that this area is completely contrary to the UNCLOS and has no legality. It also stated the breach of China’s obligations amongst environmental protection of the area and its biodiversity, and also illegal prevention of traditional fishing in the area from the fishermen of the State of Philippines.

Similar disputes around the world

As described above, from the dispute of the South China Sea between the PRC and the Philippines many general conclusions were made. These conclusions can be easily used in similar disputes around the world, however proper attention must be paid as each situation has its own unique parameters.

Such areas are many; two of the most famous are the Aegean Sea and the Caribbean Sea. In the Aegean Sea, Greece and Turkey have disputes that have started many decades before. These disputes include sovereign rights and jurisdictions over islands in the Aegean and the right of Search And Rescue (SAR) operations in its waters. In the Caribbean Sea there is a dispute along the neighboring States about the environmental protection of the area and the general maritime safety.

Firstly, the main conclusion from the South China Sea that is very useful to concentrate on is the fact that an adjudication from which one of the two States does not take part in, is considered to be non applicable. From the moment that China does not recognize the award of the PCA and its jurisdiction, no real facts and results can be expected in the region rather than a continuous conflict with unexpected incidents or accidents. So, almost in every similar case around the world, it is almost for sure that there will never be a unanimous agreement from all the sides of the dispute in order to reach a peaceful and cooperative agreement. For example, in the Aegean Sea, Turkey has been claiming (mainly under the presidency of Recep Tayyip ErdoÄŸan) that many islands are Turkish. The Greek government obviously does not accept that, referring to the UNCLOS and the Treaty of Lausanne, claiming that all Turkey’s claims are illegal. As a result, Turkey has never accepted to discuss over the conventions and treaties mentioned above, as it serves its own aims and rights in the region of the Aegean Sea.

Secondly, another main conclusion is the fact that no artificial islands can be considered to be natural. Therefore, they cannot have any maritime zones around them. This forbids the right to any State that builds an artificial island to claim any jurisdiction or sovereign right around the waters of the island, which could possibly collide to another neighboring State’s continental shelf from its mainland or a natural island with human habitation and developed economic life on it.

Finally, the existence of a “rock” just emerging over the surface of the sea does not constitute a land, capable of having continental shelf or exclusive economic zone. A conclusion that can be very useful in many disputes around the world and could force many States to reconsider their continental shelves and EEZs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the case of the Philippines against the People’s Republic of China over the South China Sea is very interesting and its award and conclusions are very useful for the whole world and the society of the international maritime law. The articles of the UNCLOS Convention were strictly followed by the CPA, reestablishing Philippines’ rights and jurisdictions on specific regions of the wider area. Moreover, it recognized the illegal actions of China in the area, concerning the protection of the marine environment and the actions against the fishermen of other neighboring States. Although these conclusions can be used for the interpretation and analysis of other similar cases and disputes around the world (e.g. the Aegean Sea, the Caribbean Sea), many other factors must be taken into consideration for the final outcome. Factors such as the general geographic status of the area, the already signed Conventions or Treaties of the conflicting States and the geostrategic importance of the area, can completely alter the final outcome of the dispute. In addition, special organizations must be formed in order to resolve similar disputes. Organizations that will be globally accepted, with representatives from all the binding States.

It must never be forgotten that a dispute over an area with great profits and benefits, can easily end up in a combat clash with many casualties from both sides. An undesirable outcome that does not promote peace in the world between States, one of the most fundamental principles of the UNCLOS.

Figure 1: Map of the South China Sea, including the nine-dash line area

References and Resources

[1]:

[2]:

[3]:

[4]:

[5]:

[6]: