Challenges to Recruiting Teachers

Throughout regional South Australia, Australia and internationally the struggle of schools to attract and retain both talented and committed graduate teachers is becoming increasingly difficult. This is particularly apparent in an era where the demands of teaching and education are at unprecedented levels. In the United States, a similar situation is evident. Ingersoll (2012) found that the ‘attrition rates of first-year teachers have increased by about one-third in the past two decades.’ Other studies more specific to Australia, have reported that the rate of new teachers leaving the profession at the end of their first year is as high as one in five (Baird et al. 2016).

There is no question that the attrition rate of graduate teachers is concerning. In my present role in the senior leadership team of a country school in regional South Australia. It is pertinent for me to use my current context as a school leader, as well as my first experience as a graduate teacher as the basis for review on how the Tools for Thinking, more specifically ‘Social Networks and Networked Communities’ are demonstrated and influential within a school environment. This report is undertaken with a view to magnify how the social networking opportunities and team dynamics that surround new graduate teachers can affect their experiences, as well as their realisation of a positive professional identity.

There are a number of contributing factors recognised as providing the impetus for new teachers leaving the profession, including ‘compensation, status and recognition’ (Rostock et al. 2014). However, increasing evidence through studies into beginning teacher induction including Alsup, 2006 and Britzman, 2003 in Rostock et al. (2014) demonstrate that a ‘teachers’ ability to accomplish the difficult task of forming a workable professional identity in the midst of competing discourses about teaching’ is having significant impact on this rate of attrition.

It is a common assessment of educational research that new graduate teachers often experience the impact and weight of responsibility in the realisation and workload of their teaching duties (Flores & Day 2006). Many new teachers recognise certain disconnections between the expectations they’re set and the actuality of the classroom. Flores; Huberman; Veenman in (Flores & Day 2006) mention ‘feelings of isolation’ and a continual struggle with an absence of clear support, encouragement and guidance. In most instances it is evident that the success of beginning teachers can be directly related to their social network, the culture of the school setting and consequently the graduate teacher’s fulfillment and development of a positive professional identity.

It is important to reflect on the connection between social networks and identity specifically their significance to a graduate teachers development. Spencer- Oatey in (Merchant 2012) explains: ‘Identity helps people ‘locate’ themselves in social worlds. By helping to define where they belong and where they do not belong in relation to others, it helps to anchor them in their social worlds, giving them a sense of place.’ Following on, a simple definition of a social network could be explained as the communal links between Actors (Vera & Schupp 2006). Knoke and Yang (2008) define ‘Actors as individual persons, or a collective, such as a group or formal organization.’

Social networks impact on ‘perceptions, beliefs, and actions through a variety of structural mechanisms that are socially constructed by the relations among entities’ (Knoke & Yang 2008). Therefore, as Vera and Schupp (2006) suggest ‘the capacities of an individual to act in society, and the implications of that action,’ (in this case: specifically a teacher in a school environment) ‘depend not only on his/her attributes but also on the pattern of relations within which he/she is located’.

It is with the concept of social network analysis that I seek to undertake an investigation into the social network characteristics of my current context in a role of educational leadership, as well as analysing the difficulties and struggles of identity and adapting to the school context, of which I experienced as a graduate teacher.

Social Network Analysis (SNA) is founded upon the derivation of a mutual relationship between the individual and society, with the intent of explaining the ‘collective properties that are defined by relational patterns and the similarities or differences between those patterns’ Haines (1988) in Vera and Schupp (2006). As Merchant (2012) explains ‘Social network analysis helps us to map the relationship between the individual and the larger social systems in which he or she participates. As a result, the relationships themselves have become the unit of analysis’ (Merchant 2012).

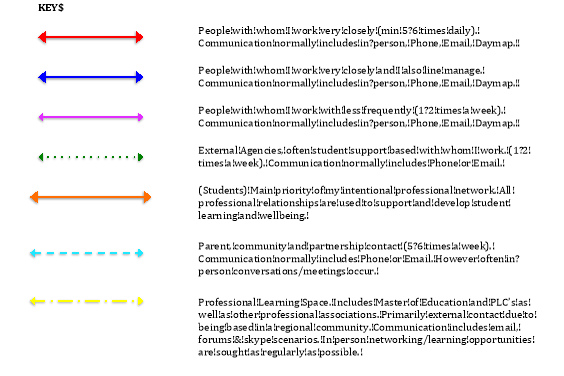

The type of network representation that will be used for analysis between my graduate context and my current leadership context will be an egocentric (Knoke & Yang 2008) intentional professional network (Baker-Doyle 2011).

Knoke and Yang (2008) describe an egocentric network as one comprised of one actor, the ego, and all other actors, the alters, with whom all the ego has direct relations. ‘Each ego actor can, in turn, be described by the number, intensity, and other characteristics of its linkages with its set of alters, for example, the proportion of reciprocated relations or the density of ties among its alters.’ (Knoke & Yang 2008)

An intentional professional network is formed around collective professional relationships, usually based within the local environment (school) and reflects ‘the network of people that teachers select to collaborate and interact with’ (Baker-Doyle 2011).

Graduate Teacher Analysis

In Figure 1, I have a visual representation of my egocentric intentional professional network and diverse professional allies as a graduate teacher.

I am passionate about teaching in rural communities so I was very excited when I received an appointment to a high school in the Mid North of South Australia. My specialisation was in Design and Technologies and I was appointed to support the existing Practical Technology teacher. When the school finalised my timetable I was placed with a difficult proposition of having to teach a higher load than normally allocated to a new teacher and secondary science. Secondary science was outside my area of specialisation, as can often be the case in teaching at a secondary rural school. However, my concern with science was that it was something I had last studied in Year 10 in high school, and now I was required to teach it at a senior level. I expressed my concern, but was assured support would be in place.

In Figure 1, the strength of the relationships are demonstrated by the arrows linking myself to the alters (all other actors). The rectangle boxes demonstrate those professionals with whom I worked on a daily basis. In the first year or two of teaching, these relationships are pivotal to ensure teachers are able to manage the workload.

Unfortunately, as is clearly demonstrated by the strength of the arrows, the strength of my relationship and support structures from those whom I needed it most, were sadly absent. More specifically the Science Coordinator, and the Technologies Coordinator, did not want to provide any form of support, induction or resources to a new teacher. This was particularly concerning due to my responsibilities in teaching science an area in which I was not confident. It was at this point in time when the ‘feelings of isolation’ (Flores & Day 2006) began. Without realising at this time, my small intentional professional network as a graduate certainly affected the development and confidence of my professional identity.

Whilst I found teaching science, and working with the coordinator, an immense struggle, I was extremely fortunate to have a fellow technologies teacher who was incredibly supportive (The relational link in Figure 1 is strong). He assisted me in managing the technologies and daily administration portion of my teaching requirements successfully. To this day, and upon reflection, I am still incredibly grateful for his support and of the mentoring role he provided. I would certainly not have continued or been present in the teaching profession without his input or the influence of the students.

Whilst some of the important relationships on the school site were incredibly difficult, I was also fortunate to have access to some Diverse Professional Allies. Baker-Doyle (2011) describes Diverse Professional Allies as ‘nontraditional support providers who are not usually considered “professionals,” such as parents, volunteers, or students. Diverse Professional Allies are invested in the professional growth of the teachers’ (Baker-Doyle 2011).

The Diverse Professional Allies are represented in Figure 1 through the hexagonal shapes. A regional group of Technologies educators and my fellow university graduates were recognised as one type of Diverse Professional Ally. Each of these groups were able to provide me with insights from across the state and encouragement to continue as well as the challenge and support to drive improvement in my existing professional practice.

The most significant Diverse Professional Allies that I was fortunate to have in my social network were the students. The students, amongst all of the difficulties with staff, made it all make sense. Their personalities, enthusiasm and individual perspectives made the time in class worthwhile. They were the incentive to keep going, to go out and research more about science, to continually improve my delivery. Baker-Doyle (2011) explains ‘Diverse Professional Allies… help teachers challenge the traditional norms of the school or teaching and break out notions about curriculum or practice that limited the teachers’ personal involvement in the curriculum’ (Baker-Doyle 2011). This was certainly the case for the students in my network.

Figure 1 – Matt Linn’s Graduate egocentric Intentional Professional Network and Diverse Professional Allies

Senior Leader Analysis

8 years on, my current context is also represented in an egocentric intentional professional network as demonstrated in Figure 2. Throughout the time since I was a graduate teacher, my intentional professional network has changed considerably. The development of my confidence and responsibilities over time have impacted on the size of my social network in a professional environment.

My teaching role changed from its traditional sense approximately 4 years ago when I took on a position of directing information technology (IT). The role of IT in schools has dramatically challenged the landscape and traditional structure that schools have often used. Core school operational management systems were now all being run through IT. The whole school required IT support and knowledge to manage the abrupt changes that were taking place. Many traditional school operations were required on systems never previously used. Almost overnight, my role in IT became one supporting an entire Mid North Partnership. Whilst this was a significant responsibility, the effect this change had on my social networks particularly my intentional professional network, was transformational. This was a turning point for me as it clearly demonstrated the power and importance of having effective, but also diverse social networks.

Following on, it has been possible for me to focus on building strong intentional professional networks and appreciate the support as well as realising the vital importance of effective social networks for the teaching profession.

The sum of the relational links in Figure 2, are much stronger and dependable in my current context. The change in responsibilities including different forms of line-management, as well as working in senior leadership have meant that type of relations I now hold have altered considerably. Rather than only having the capacity to work with one or two key people within my intentional professional network, I have the opportunity of working very closely, with purpose, alongside a number of people throughout the week. The opportunity to relate to a number of people cannot be understated when reflecting on the significance of social networks, graduate support and the development of a positive professional identity.

It is also important to note how the development of confidence and professional experience that is gained over time certainly has a significant effect in social network development. Knoke and Yang (2008) explain the dynamic nature of relations: ‘structural relations should be viewed as dynamic processes. This principle recognizes that networks are not static structures, but are continually changing through interactions among their constituent people, groups, or organizations’ (Knoke & Yang 2008).

In my current context as a senior leader (Figure 2) I am now able work with a team across the school to reflect on our own school context how our social networks can effect a graduate teachers development. A significant focus on building a positive school culture have meant that the focus is now centred on support, induction and mentoring. Reinforcing the importance of culture on networks and professional identity, Flores and Day (2006) in their research found that perceptions of school culture and leadership impacted upon the ways in which new teachers learned and their identity developed over time’.

Thus, moving forward, the focus for schools and teacher education, must be in bolstering the importance of effective professional support networks for all staff. Whilst the focus of this report has been centred on new graduate teachers, the impact of networks on the establishment and development of a positive professional identity for all teachers cannot be understated. Induction programs, mentors and a supportive culture are an implicit responsibility of all schools. We all have a mutual ‘responsibility for ensuring that new teachers have and are able to sustain and put into practice a set of values which represent aspirations for a passion for high quality teaching and learning’ (Flores & Day 2006). Positive social networks are a paramount in ensuring new teachers are supported for long term engagement in the teaching profession.

Figure 2. Matt Linn’s Senior Leader – Intentional Professional Network and Diverse Professional Allies.

Reference List

Baird, J, Stroud, G, Goss, P & Clark, L 2016, The Drum Friday September 16: The figures are somewhat better in five Australian teachers leaving the profession early, ABC.

Baker-Doyle, KJ 2011, ‘Looking at networks: network types and the networking practices of new teachers’, The networked teacher : how new teachers build social networks for professional support, Teachers College Press, New York, pp. 18-32.

Flores, MA & Day, C 2006, ‘Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study’, Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 219-232.

Ingersoll, RM 2012, ‘Beginning Teacher Induction What the Data Tell Us’, Phi Delta Kappan Magazine, vol. 93, no. 8, pp. 47-51.

Knoke, D & Yang, S 2008, ‘Network fundamentals’, Social network analysis, no. 2, pp. 4-14.

Merchant, G 2012, ‘Unravelling the social network: theory and research’, Learning, Media and Technology, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 4-19.

Rostock, R, Yoon, S, Remillard, J & Wood, D 2014, Developing a workable teacher identity: Building and negotiating identity within a professional network, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, University of Pennsylvania.

Vera, ER & Schupp, T 2006, ‘Network analysis in comparative social sciences’, Comparative Education, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 405-429.