Challenges to the UK Building Industry Regulations

Literature Review

The Building (construction) industry is complex in nature. It involves several stakeholders with different procedure, process and perception; therefore, there are bound to be conflicts and disputes amongst them.

Jaffar et al. [Jaffar, Abdul Tharim, et al. 2011] noted that a study undertaken by Kumaraswamy and Yogeswaran [Kumaraswamy and Yogeswaran 1998] provided a good reference of the common sources of construction disputes that are likely related to contractual matters, including variation, extension of time, payment, availability of information, quality of technical specification, administration and management, failure to meet client’s expectations and determination.

Conflict may be as a result of difficulties in communications between individuals, barriers between personal and professional relationships, informal agreements etc. Conflict are also known to produce tension and distraction amongst team members or stakeholders, from performing their agreed task.

Gould [Gould] explained that conflict may arise in construction project, and taking adequate steps in avoiding them is very important. Effective communication, identifying objective solutions and avoiding conflict can help in achieving a hurdle-free project lifecycle. In the construction industry, commercially based settlement is frequently used, either in negotiation or by mediation. Time and money can be saved by using a mediator or other ADR (Alternative Dispute Resolution) process.

The literature review of this research will cover the UK building Industry; the building regulations applicable in the UK; causes of conflict and how they can be managed.

3.1 The UK Building Industry

The UK construction industry employs 2.9 million people, approximately 10% of all jobs (in over 280,000 businesses). It contributes nearly £90bn to the UK economy, 6.7% of the total. The global construction output is expected to increase from around $8.5 trillion today to $12 trillion in 2025. The UK is considered to be the sixth largest green construction sector in the world, with around 60,000 jobs to support the insulation sector alone by 2015 [HM Government].

As stated by HM Government [HM Government], the population of 2.9 million people is divided into the following trades:

- Executive and managerial – 11%

- Painters and decorators – 3%

- Civil, mechanical, electrical engineers – 5%

- Bricklayers, masons, roofers, tilers – 3%

- Metal, electrical and mechanical trades – 10%

- Architects, town planners, surveyors – 6%

- Carpenters and joiners – 7%

- Plant and machine operatives and drivers – 7%

- Plasterers, glaziers and other trades – 5%

- Plumbers and heating & ventilation engineers – 5%

- Other occupations – 37%

Building Regulations in the UK

In the United Kingdom, Building regulations are statutory instruments that ensure that the policies set out in appropriate regulations are carried out as required. Building regulations that are applied across in Scotland are set out in the Building (Scotland) Act 2003 while across England and Wales, Building regulations applied are set out in Building Act 1984.

The Building regulations for the UK are generally divide into three:

- England and Wales;

- Scotland; and

- Northern Ireland.

In England and Wales, the department for Communities and Local Government (CLG) is responsible for Building Regulations. The Building regulations’ legislative framework principally made up of the Building Regulations 2000; and the Building (Approved Inspectors etc.) Regulations 2000. The aim of these regulations is to provide standards for most aspects of building’s construction, including its structure, fire safety, thermal efficiency, sound insulation, drainage, ventilation and electrical safety. Furthermore, Electrical safety was included in January 2005 to reduce the number of fatality, injuries and fire caused by faulty electrical installation [KnaufInsulation].

As stated by England and Wales Planning Portal [UK National Archives], “the Building Act 1984 is the primary legislation under which the Building Regulations and other secondary legislation are made.

The many powers of the Building Act 1984 include those for:

- Setting the status of Approved Documents

- Setting the status of Approved Documents

- Dangerous structures

- Demolition of buildings

- The role of Approved Inspectors

- Enforcement of Building Regulations

- Powers of entry to premises etc.

As noted in the Building and Buildings, England and Wales – The Building Regulation 2010 [Legislation.gov.uk], the regulations covers the following:

- Control of Building work

- Notices, Plans and Certificates

- Supervision of Building Work Otherwise than by Local Authorities

- Self – Certification Schemes

- Energy Efficiency Requirements

- Water Efficiency Requirements

- Water Efficiency

- Information to be provided by the Person Carrying Out Work

- Testing and Commissioning

- Miscellaneous

In Northern Ireland, the department of Finance and Personnel (DFPNI) for Building regulations. The Building regulations (Northern Ireland) Order was enacted in 1972, which was subsequently amended in 1978 before finally replaced by the Building Regulations (Northern Ireland) Order 1979 (as amended 1990). The current regulations are the Building Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2009. The Building Regulations set the requirements and standards that can be attained reasonably, having regard for the health, safety, welfare and comfort of people in and around buildings and others affected by buildings or building matters [KnaufInsulation].

The Scottish Building Standards Agency (SBSA) is responsible for the Scottish building standards system. The Building regulations’ legislative framework in Scotland is principally made up of the Building (Scotland) Act 2003 and the Building (Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2004. The Scottish Building Standards Agency will work on behalf of Scottish Ministers to [KnaufInsulation]:

- Promote the health, safety, welfare and comfort of people in and around buildings;

- Encourage the conservation of fuel and power; and

- Encourage the achievement of sustainable development.

Planning permission are different from Building regulations; they are concerned with appropriate development, the neighbourhoods’ appearance, and nature of land usage while Building regulations control how buildings are designed and construction (building specifications).

Definition of conflicts

Most people do not recognise the difference between “conflict” and “dispute”. Many scholars have differentiated between the two terms. As defined by Burgess et. al [Burgess and Spangler], “Disputes are defined as short-term disagreements that are relatively easy to resolve. Long – term, deep-rooted problems that involve seemingly non-negotiable issues and are resistant to resolution are referred as Conflicts.”

A dispute can result when a claim or assertion made by one party is rejected by other party and that rejection is not accepted [Kumaraswamy and Yogeswaran 1998]. This shows that a dispute is more likely to occur when the conflicting parties exhibit an action or arguments to a controversy.

Jaffer et al. [Jaffar, Abdul Tharim, et al. 2011] noted that according to Thomas [Thomas 1992], there are three themes among the definitions of conflict. The first, it is regarded as a perception issue, whether conflict exist or not. The perceived difference may not be real but conversely if the difference is real but not perceived, there is no conflict. The second, there is interdependence among parties (i.e. each has the potential to interfere with the other). Thirdly, there are issues of opposition, blockage and scarcity. Resources (money, power and prestige) are limited. Their scarcity creates blocking behaviour.

Conflict and dispute are two distinct notions. Conflict tends to exists where there is incompatibility of interest, and it is pandemic. Conflict can be managed to an extent at which a dispute is avoided to occur from the conflict. Dispute require resolution, and it is associated with defined justiciable issues and third party intervention [Fenn and Lowe 1997].

Costintino and Merchant [Costintino and Merchant 1996] defined “conflict as the fundamental disagreement between two parties, of which a dispute is one possible outcome (conciliation, conflict avoidance, or capitulation are other outcomes)”. Furthermore, conflict is a state rather than a process. Participating parties with different interests, values, or needs may be in a state of conflict, which may be considered to be latent (meaning ignored) or manifest resulting in a form of dispute or disputing process. Therefore, a conflict can exist without a dispute, but a dispute cannot exist without a conflict [Yarn 1996]

Conflict can be defined as a social phenomenon which can arise when people interact and pursue common goals. The beginning of a disagreement if often when two people or parties have differing interests and work against one another in order to achieve their set objectives. Furthermore, conflicts only carry destructive potential, they can also offer many opportunities for change, development and innovation [Proksch 2016].

Gorse [Gorse 2003] defined conflict as “any divergence of interest, objectives or priorities between individuals, groups or organisation, or non-conformance to requirements of a task, activity or process”. Conflict is not only inevitable in the construction industry, it is often desirable.

The numerous definitions shows that scholars look at conflicts and disputes from different angles. However, most researchers are of the opinion that conflict and disputes share the same definition that is generally involve disagreement regarding interests or ideas [Kumaraswamy and Yogeswaran 1998]. This research adopts the view that conflict and dispute are the same.

Types of Conflicts

Identifying what type of conflict that exist is very important, as it will reduce the risk of tackling the wrong problem. Each conflict has a multitude of different facets. In resolving a conflict, it is often necessary to determine the root cause before solving the actual problem. Depending on the causes, there are six different basic forms of conflict, namely [Proksch 2016]:

- Circumstantial conflicts

Circumstantial conflict are referred to those conflicts that are caused as a result of differing, insufficient or incorrect information, as well as differing interpretations of this information. An example is “A car accident resulting in damage to property”. Solution to such conflict is normally on factual level: obtaining all required information, clarify all facts, establish agreement on facts assessed and if necessary, employ the assistance of independent experts.

Circumstantial conflict is more about who compensates whom for the damages caused and in what amount. Emotions that arises in this type of conflicts usually disappears after clarification of the issue.

- Conflicts of interest

This type of conflict is not about facts but differing interests. For example in a neighbourhood, conflict between a bar owner and a resident due to noise disturbance, the former has a legitimate right to have as many customers as possible. In this context, the bar owner may be required to play loud music. The resident also has a legitimate interest in peace and quiet.

It is advisable to identify the respective interest and requirements. These are sometimes not clear by the positions of the parties involved. Once legitimate interest are revealed, it makes it easier to resolve, as requirements are often broadly-based. Consequently, these increases the possibility of various options.

- Relationship conflicts

Relationship conflict is caused by problems of an emotional nature. These conflicts are as a result of feelings like fear, frustration, similar emotions, envy, unmet expectations or reoccurred misunderstandings. Something of value to one person may not be of interest to the other person e.g. punctuality. A relationship conflict may arise amongst parties where one perceive the unpunctuality of the other as a gesture of contempt. The parties involved should be given the opportunity to express their feelings; and the underlying aspirations and needs of each individual should be understood by parties.

- Conflicts of values

Differing ideals and principles clash may result in ‘Conflicts over value’. A classic example of this form of conflict is ‘disparate religious norms’, but a more general example is when values such as seniority on one side and performance orientation on the other come into conflict. In some cases, both principles – in varying degree – are valued.

Establishing a common value footing will aid ‘conflicts of values’ resolution. In an event where a common basis for discussion cannot be determined, a decision should be taken at a higher instance or by a court.

- Structural conflicts

This form of conflict does not result from difference between people but from differences in structural factor. There is typically an area of tension between sales and construction areas of a company, a latent conflict, because they set definite priorities and pursue different goals. Another example is the tension that exist between two opposing lawyers in a trial, they engage in conflict with one another based on the logic of the legal system.

In search of a solution, It is advisable to focus on the development of regulatory and coordination processes, in a view to constructively manage the permanent tension.

- Inner conflicts

This form of conflict is the world of thoughts and feelings of one person. Everyone’s desires, goal or role requirements varies; therefore, contradict one another. For example, the thought of “Shall I finish the assignment today and get home later, or put it off until tomorrow and have dinner with my family?” In this instance, the role of a family person and the role of a professional come into conflict. Open conversation with someone may help in dealing with serious inner conflicts.

Figure 1: Types of Conflicts

As explained by Gorse [Gorse 2003], conflict can be perceived to be natural, functional and constructive or unnatural, dysfunctional, destructive and unproductive. Challenges, disagreements and arguments relating to tasks, roles, processes and functions, may result from ‘functional conflict’ which often involves detailed discussion of relevant issues. The advantages of ‘function conflict’ are:

- Helping to expose problems;

- Reduce risks;

- Integrate ideas;

- Produce a range of solution;

- Develop understanding;

- Evaluate alternatives; and

- Improve solutions.

Unnatural conflict can be defined as “where a participant enters into encounter intending the destruction or disablement of the other party”. Dysfunctional conflict can be as a result of personal insults, criticism that encourages self-ego and comments that lack regards for others feelings. This type of conflict is not aimed at improving task performance [Gorse 2003].

Causes of Conflict in Construction Industry

Conflict develops in multidisciplinary building teams as group members tend to impose their team objectives on others, in order to change others’ beliefs or actions. Furthermore, conflict may result due to a failure to develop and manage people’s expectations. For example, the inexperience of some clients means that when explaining the construction process, it has be detailed. Explanation should broken-down to their level of understanding. When problem arises and decision need to be made, clients require unbiased and professional responses but this is often inconsistent because information or responses are offered from different professionals. Information from professionals may differ even if they provide the same service because they tend to concentrate on aspects closely associated with their profession, training and experience [Gorse 2003].

Conflicts are often not conspicuous, they are mostly recognisable by their symptoms which may include [Proksch 2016]:

- Opposition, rejection: The conscious or unconscious attempt to prevent the opponent in achieving his objectives, in the work that is carried out carelessly or information is not communicated.

- Withdrawal, indifference: The parties involved loses motivation to work as well as the need to open up emotionally. This often referred to as “inner resignation”.

Kumaraswamy [Kumaraswamy 1997] identified 20 common causes of construction conflict and disputes, which are as follows:

- Failure of respond to issues on time

- Lack of communication among the team members

- The mechanism is not clear in providing information

- Poor management, control and coordination

- Failure to determine responsibility in accordance with the contract

- Estimation error

- Delayed in providing information

- Design errors and specifications

- Pictures and specifications are incomplete

- Calculation of incorrect work progress

- Lack of experience of consultants

- Lack of contractor management, supervision, and coordination

- Delay of jobs

- Failure of plan and implement change of work

- The failure to understand the price of the work or the offer price correctly

- Lack of understanding of the existing agreement in the contract

- Employment contracts and the complete lack of construction documents

- The lack of clarity of document in the distribution of work flow

- Non clarity of terms in the contract documents

- The big difference in understanding of contracts in foreign languages within the same contract

As noted by Jaffer et al. [Jaffar, Abdul Tharim, et al. 2011], Hohns [Hohns 1979] opined that construction disputes have their instinct nature and characteristics; therefore, the sources of disputes will vary from one project to another. In his study, he identified five primary sources of construction disputes that includes existence of errors, defects or omissions in the contract documents, failure of someone to count the cost of an undertaking at the beginning, changed condition, consumer reaction and people involved.

Jaffer et al. [Jaffar, Abdul Tharim, et al. 2011] explained that conflict causes identified by researchers are summarised into three categories, namely: causes due to behavioural, contractual and technical problems.

- Conflicts causes due to behavioural problems

Human interaction, personality, cultures, perception and professional background amongst team members are common behavioural problems. Other causes of conflicts in human behaviour are individual’s ambition, frustration, dissatisfaction, desire or growth, communication and level of power, fraud and faith.

It is one thing to lose money in a contractual issue, but it is a lot to lose face. People tend to protect their integrity and pride no matter the cost. Once one’s ego involved can survive, disputes tend to be more easily resolved. Everyone wants a better future and the opportunity to increase the self-recognition; therefore, goal realisation and increase of authoritative power will help in resolving disputes.

- Conflict causes due to contractual problems

The stakeholders in a project are governed by a contract which defines their obligation to each other, and also the exchange of construction materials and services for money. MacNeil [MacNeil 1974] defined contract as “a promise or the set of promises for the breach of which the law give a remedy or the performance of which the law in some way recognises as a duty”.

As indicated in a study undertaken by Kumaraswamy & Yogeswaran [Kumaraswamy and Yogeswaran 1998], the sources of construction disputes are mainly related to contractual matters including variation, extension of time, payment, quality of technical specification, availability of information, administration and management, unrealistic client expectation and determination.

Standard contract documents in the building industry are guided by codes and regulations. They provide common ground for contractual definitions clarifications, thereby making conflict less likely in construction operations and specific project requirements.

- Conflict causes due to technical problems

Projects come with uncertainty, most times surrounded around the technicality of the project. Technical disputes due to uncertainty are considered as the most common issues. Technical disputes include engineering clarification which is considered as a part of engineering making processes. For example, ‘Request for Information’ (RFI) which is a tool used for clarifying differences in understanding during project operation, is used to resolve issue onsite before they develop to technical dispute. Such dispute can be resolved by project personnel with appropriate expertise.

The engineering decision making process is quite straight forward and reasonably justifiable for all participants. The ways of resolving technical disputes in project management is different from the resolution of contractual disputes during project operations. The design deficiency is generally regarded as being beyond an error of omission. Design error significantly alter the means, methods, environment, duration, or the conditions of the construction process. In the construction industry, design errors are common in foundations, frame and enclosure, and in space utilisation.

As explained by Rauzana [Rauzana], Susila [Susila] opined that on one hand the contractor’s attention is on project completion in accordance with specified schedule and attempt to gain financially, while on the other hand the owner needs excellent asset at economical prices. Each party goal contradict with another; therefore, it may result in circumstances which could lead to conflict. The factors of conflicts are owner, consultants, contractors, contracts and specifications, human resources and project conditions

Conflicts in the building industry: Negatives or Positives?

Proksch [Proksch 2016] explained that conflict has its negatives and positives, and may consumes valuable resources: time and money. When conflict escalate and develop into power struggle or paralyses an organisation, this becomes a commercial problem.

The risk that arises from conflicts in an organisation affect various areas, which are as follows [Ref. 6]:

- Stress and pressure on employees: Conflict experienced by participant are often stressful and are associated with anxiety, aggression, excessive demands, lack of esteem and similar feelings. Decline in productivity may be as a result of stress, which may further cascade to demotivation, inner resignation and absenteeism spread.

- Fragmentation of teams: Communication behaviour between opponents is passive or aggressive. Participants are disparaged and increasing value may be placed on allies. Avoiding or insulting each other arises. In some cases, it may result in deception, theft, sabotage and hostile behaviour.

- Unproductive usage of time: The time that should be spent on carrying out work is taken up by conflicts. Colleagues focus more on talking about the conflict, speculating about causes and relationship, people blaming each other or scheme, seeking information, inflict agony on one another, etc.

- Staff turnover and sick leave: Lengthy conflicts results in higher levels of absenteeism due to stress or sickness. Chronic unresolved conflict are suggested to cause up to 90% of dismissals as well as in at least 50% of employee resignations. Running costs increases as a result of staff losses, recruitment and training of new employees.

The comments above does not mean that conflicts are principally negative. As earlier noted, conflict has its advantages as well. Conflicts are perceived as the rule of human co-existence; the way it is being manage determines how successful organisations are in solving their problems, and consequently in protecting their future. Conflicts have positive aspects, which are as follows [Proksch 2016]:

- Conflicts indicate problems: Problems or misunderstandings become visible and noticeable through conflicts. Tension between participants is an indicator of ‘Need for Action’.

- Conflicts trigger change: Conflicts provide opportunity for change. At this point, actions or decisions are taken to trigger change and thereby prevent deadlock.

- Conflicts arouse interest and curiosity: Conflicts encourages great enthusiasm to human co-existence. They would lead to tension, curiosity, fostering interest and stimulating the search for creative new solutions and innovations.

- Conflicts strengthen relationships: When conflicts are successfully overcome by both sides, they provides enduring relationships. Friendship tend to get stronger when they go through ‘through and thick’ and finally settle their differences. Conflict – free relationships are often cursory. Frictions will produce understanding amongst participants which will improve trust.

- Conflicts strengthen group cohesion: Having constructive debate will result in knowing preferences, strengths and weaknesses of colleagues or participants. Making it easier to develop trust and to recognise one’s weaknesses.

Conflict Management in Organisations

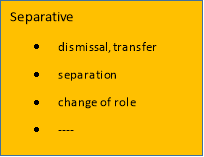

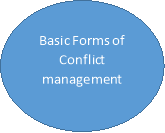

Proksch [Proksch 2016] noted that the survey carried out by the working group “Internal Mediation” concluded that methods of conflict management can be reduced to four basic forms. In attempting to settle conflict, the parties to the disputes can be separated or brought together. However, attempts can be made to resolve the conflict on an issue-related or individual -related basis. The four basic forms of conflict management are as follows:

- Separative measures

- Issue – related measures

- Integrative measures

- Individual – related measures

TraditionalComplementary

Figure 2: The four forms of conflict management [(Proksch 2016)]

1.1.1 Separative Measures

Separative measures are focused on separating the parties, thereby eliminating the conflict. Examples of this are dismissal or transfer of an employee or employees from their work base to other locations of the organisation. Another example is where the Project manager in a conflict with the site engineer, one of them is transfer to another location to avoid issues. These forms are often used and constitute a “classic” form of conflict management, whereby existing conflicts are made to vanish from the face of the earth relatively quickly and effectively [Proksch 2016].

Proksch [Proksch 2016] suggested that if a similar conflict arises frequently, that means it is probably a structural conflict. Therefore, the conflict is not related to the person but to his/her organisation and the management system. On this occasion, it is advisable to apply an integrative form of conflict management to get to the root cause.

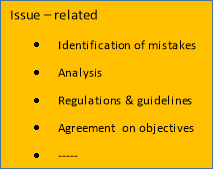

1.1.2 Issue-Related Measures

Issue – Related Measures is implemented where the organisational or technical solution is sought independently of the conflict participants. First step is to identify the mistake and analyse it; then draw up regulations, guidelines or standards aimed at preventing the recurrence of the same conflict.

In the construction industry, regulations, guidelines and standards that are in relation to the industry and tasks should be consulted. Effective tools such as work procedures, organisational chart, procurement procedures, business process models and so forth should be used to organise the way in which people work together.

An example of issue – related measure is increasing scarce resources, and they are a frequent cause of conflict. The basis of the conflict is eliminated as result of the lower degree of mutual dependency when the bottleneck is removed.

These methods are bound to be successful if the conflict is caused by unclear guidelines or boundaries or when assignment are not explicit thereby resulting in misinterpretation. Method fails when the causes are perceive to be only a pretext, and other underlying problem such as personal issues or organisational culture are the main causes.

1.1.3 Individual – Related Measures

Individual – Related measures focuses on seeking solution at an individual level. Sometimes personal discussions are conducted or coaching offered to the affected individual. If the conflict cannot be resolved through discussions, the task of resolving the conflict may be delegated to someone.

Disagreements by the categorisation of events into good or bad, right or wrong make it easily to resolve. The judicial system operates on this principle in order to ensure order and security. In the professional context, this approach has its shortfall because conflicts do not only arise on individual level but a large number of influencing factors play a role together that result in conflict: organisational frameworks, customs, power structures or limited resources.

The downside of this approach to conflict management is that while the work with an individual develops adequate strategies, a consensual solution cannot be developed involving other party to the conflict.

1.1.4 Integrative Measures

Integrative measures involves collective parties examining the causes of conflict together. A clarifying conversation, team development or mediation are examples of integrative measures. These approaches are seen as a means of fostering direct communication, creating favourable framework conditions for disassembling deadlocks and improving interaction, thereby resolving the conflict.

It is advisable for parties to firstly seek discussion with another when dealing with the problem. Often, this helps in dealing with conflict. However, danger may exist when participating parties blame each other’s point of view and consequently being caught up in unnecessary argument. Seeking solution should be all parties’ priority.

The advantage of this measures is that it will gradually restore the damaged discussion culture which will foster team spirit and effective communication.

Gould [Gould] stated that “there are three main techniques for problem resolution:

- Negotiation: The problem – solving efforts of the parties themselves;

- Mediation or conciliation: A third party intervening in order to assist the parties to resolve their difficulties;

- An adjudicative process: A final outcome is determined by a third party. This is of course includes construction adjudication, but litigation and arbitration also lead to binding decisions based on an assessment of the facts and law.”

As stated by Ock et al [Ock and Han 2003], conflict management in addressing the problem of conflicts with several methods are as follows:

- Impose one’s views at the expense of the strength of another

- Minimise the differences and emphasise togetherness to issues of conflict.

- Withdrawing from the real contradictions and conflict situations

- Consider the various issues, bargaining, and look for ways of settlement or that bring satisfaction to the parties involved in the conflict

- Problem solving

Conflict Management (Strategies)

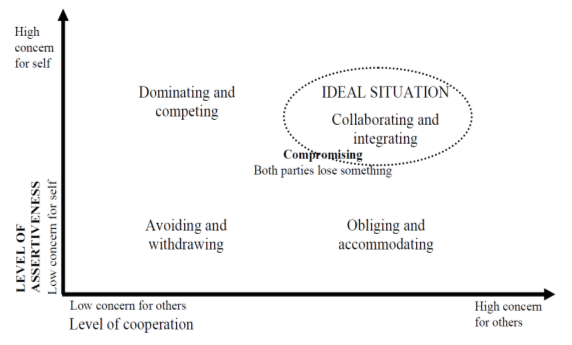

Gorse [Gorse 2003] opined that most management models work on the principle that people undertake their duties with a level of concern for their self and for the benefit of their product, For example the approach to management strategies by Blake and Moulton’s (1964). Furthermore, Pruitt and Rubin (1986) suggest that the approach has changed by replacing concern for product with concern for others. Figure 1 shows how the use of these two simple dimensions’ various approaches to conflict management have be categorised.

Figure 1: Conflict handling styles [Gorse 2003].

As explained by Gorse [Gorse 2003], each of the conflict management styles has a useful purpose, although parties are required to consider how the outcome would affect the working relationship. The implementation of different conflict management strategies is with a goal of finding solutions that benefits all and offers the optimum strategy. Each of the processes has its time and place, but to maintain relationships between clients and supplies, project managers must ensure that concerns are balanced for themselves and others, driving negotiations towards the ideal positions.

Conflict Avoidance

Gould [Gould] stated that “simple steps that can be taken to avoid conflict, and these include:

- Good management: Proactive planning and management of future work, as well as raising early issues of concern can avoid disputes;

- Clear contract documentation: Ambiguities in contract documents can be lead to argument, disagreement and dispute. Focusing on the specific details of the particular project (rather than generalisation) is important;

- Partnering and alliancing: Building cooperation between the project participants and fostering team spirit is extremely valuable;

- Good project management: Planning ahead and managing generally and specifically the time, money and risks associated with the project are crucial;

- Good client management: Understanding the client’s objectives and communicating issues and problems early on are fundamental;

- Good constructor management: A regular objective assessment of progressing and the costs relating to a project also involves communicating well with the constructor and dealing positively and objectively with problems that arise. Do not ignore problems in the hope that they might go away;

- Good design team management: Good information is crucial

- Record keeping: Disputes can often be resolved by retrospectively considering records that have been kept during the project. However, those records are often not sufficiently detailed.”

References

BURGESS, H. and SPANGLER, B., Conflict and disputes. [online] Available from: http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/conflicts-disputes [Accessed 02/10 2017]

COSTINTINO, C.A. and MERCHANT, C.S., 1996. Designing Conflict Management Systems: A Guide to Creating Productive and Healthy Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey – Bass.

FENN, P. and LOWE, D., 1997. Conflicts and dispute in Construction. , pp. 513-518

GORSE, C.A., 2003. Conflict and Conflict management in Construction 2017(02/16),

GOULD, N., Conflict avoidance and dispute resolution. [online] Available from: http://www.fenwickelliott.com/sites/default/files/nick_gould_-_conflict_avoidance_and_dispute_resolution.indd_.pdf [Accessed 02/11 2017]

HM GOVERNMENT, Construction. [online] Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/229339/construction-sector-infographic.pdf [Accessed 02/07 2017]

HOHNS, M.H., 1979. Preventing and solving construction contract disputes. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company (May 1979).

JAFFAR, N., ABDUL THARIM, A.H. and SHUIB, M.N., 2011. Factors of conflict in construction industry: A literature review. [online] Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1877705811029651/1-s2.0-S1877705811029651-main.pdf?_tid=3d4c9b9c-10b3-11e7-add8-00000aacb360&acdnat=1490374947_205214f3e44f8795be8e7847761b9b31 [Accessed 02/11 2017]

KNAUFINSULATION, Building regulations. [online] Available from: http://www.knaufinsulation.co.uk/sites/knaufuk/files/downloadfile/1_3-building-regulations_1.pdf [Accessed 02/11 2017]

KUMARASWAMY, M., 1997. Conflicts, Claims and Disputes in Construction. Journal of Engineering, Construction, Architecture Management, 4(2), pp. 95 – 111

KUMARASWAMY, M. and YOGESWARAN, K., 1998. Significant sources of construction claims. 1(15), pp. 144 – 160

LEGISLATION.GOV.UK, Building and buildings, england and wales

the building regulations 2010. [online] United Kingdom: Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/2214/pdfs/uksi_20102214_en.pdf [Accessed 02/11 2017]

MACNEIL, I.R., 1974. The many futures of contracts. Southern California Law Review, 47(691),

OCK, J.H. and HAN, S.H., 2003. Lesson Learned form Rigid Conflict Resolution in an Organisation: Construction Conflict Case Study. Journal of Management in Engineering,

PROKSCH, S., 2016. Conflict Management. Switzerland: Springer.

RAUZANA, A., Causes of conflicts and disputes in construction projects. [online] Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309275246_Causes_of_Conflicts_and_Disputes_in_Construction_Projects [Accessed 02/11 2017]

SUSILA, H., Causes of Conflict in the Implementation of Project Construction. Journal of Engineering and Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, 11(15),

THOMAS, K., 1992. Overview of conflict constructive and destructive processes.

UK NATIONAL ARCHIVES, Building act 1984. [online] United Kingdom: Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20151113141044/http://www.planningportal.gov.uk/buildingregulations/buildingpolicyandlegislation/currentlegislation/buildingact [Accessed 02/07 2017]

YARN, D.H., 1996. “Conflict” in Dictionary of Conflict Resolution. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.