Description of a Maintenance Organisation

Description of a Maintenance Organisation with Suggested Developments to Improve Cost Effectiveness

Â

Table 1: Key Terms and Abbreviations

|

Term / Abbreviation |

Definition |

|

CM |

Corrective Maintenance |

|

CMMS |

Computerised Maintenance Management System |

|

DCC |

Dublin City Centre |

|

FM |

Facilities Manager |

|

FT |

Facilities Technician |

|

GO |

General Operator |

|

HR |

Human Resources |

|

IFM |

Integrated Facilities Management |

|

IR |

Industrial Relations |

|

IT |

Information Technology |

|

KPI |

Key Performance Indicator |

|

NSC |

National Services Centre |

|

OCS |

One Complete Solution or Outsourced Client Solutions |

|

PM |

Preventive Maintenance |

|

RIME |

Ranking Index for Maintenance Expenditures |

|

TUPE |

Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) |

|

WIOF |

Water Industry Operating Framework |

|

WO |

Work Order |

Â

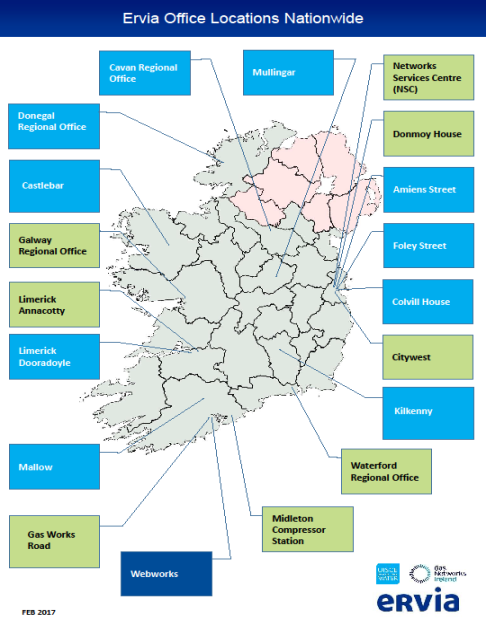

This report provides analysis of the Ervia Facilities department and investigates options for improving cost effectiveness. Ervia is Ireland’s biggest utility provider and has 2,000 office based employees in 19 locations across the country.

Ervia has availed of the Integrated Facilities Management (IFM) model for delivery of maintenance with OCS Management Services being the chosen provider. The cost to Ervia of this service is €3,000,000 per annum. This 3 year contract is set to expire at the end of 2017.

Industrial relations (IR)

Mention overall savings expected. €500,000 in total with a €100,000 reduction of the IFM contract value.

The Maintenance Organisation that I have chosen to base this report on exists within the facilities department of Ervia.

Ervia is Ireland’s biggest utility provider. It is a semi-state body, formed in 2014 and is the parent company of Irish Water and Gas Networks Ireland. Through its business, Aurora Telecom, it is also a provider of dark fibre broadband infrastructure.

A Shared Services business unit was created within Ervia that comprises of Facilities, Human Resources (HR), Information Technology (IT), Accounts Payable, Procurement and Major Projects departments. Shared Services would count Irish Water and Gas Networks Ireland as de facto customers.

The Facilities department are responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of 19 offices throughout Ireland. There are some 2,000 employees working from these offices. Site security, cleaning, catering, capital projects and fleet management also fall within the remit of the department but for this report, we will focus solely on the maintenance of the office buildings.

The maintenance or ‘hard services’ of the offices is outsourced to the IFM company, OCS Management Services as part of a 3 year contract that is due to expire at the end of 2017.

OCS Management Services is part of the wider OCS group. The acronym was originally defined as Office Cleaning Services but is now interchangeably explained as being either One Complete Solution or Outsourced Client Solutions. It has a truly global reach with operations in over 50 countries and provides a full range of facilities related services.

For simplicity, we will refer to the OCS Management Services team as OCS for the remainder of this report.

The changes I suggest will be recommended for implementation at the beginning of the next IFM contract in January, 2018 and will involve structural overhaul of both Ervia and OCS’s facilities maintenance teams. This next IFM contract is set to last 5 years.

2.1 Office Locations

One of the main challenges for managing maintenance on the Ervia contract is the geographical spread with offices dotted throughout the country. See Figure 1 for all office locations.

It would be far easier to deliver Facilities service if the office staff were more centrally located but being a national utility, Ervia must tie in with the multitude of county and city councils spread throughout the country.

Figure 1: Ervia Offices Locations

Figure 1 shows the locations of Ervia offices throughout Ireland.

2.2 Contract Value

The hard services maintenance contract comes at a cost of €3,000,000 per year to Ervia.

It is based on a Cost Plus model i.e. all Preventive Maintenance (PM) is delivered as part of the contract value with Corrective Maintenance (CM) activities charged as additional costs.

Additional costs can accumulate up to a value of €500,000 per year.

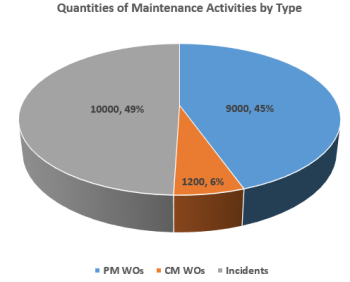

2.3 Work Quantities and Types

Facilities maintenance differs from industrial maintenance in that items that require attention may be observed by either office or maintenance staff. Office staff will generally tend to report less serious matters, while maintenance staff typically report the issues which require more urgent attention.

In order to separate the ‘noise’ of often trivial matters observed by office staff from the technical issues observed by maintenance staff, Ervia has developed an Incident Management process. Issues are raised by the office staff using an online incident management system. The raised incidents are dealt with by the maintenance staff along the following lines:

- If the item involves a non-technical fix e.g. increase in room temperature or lubricating a squeaking door hinge, the incident can be closed once this action is completed.

- If the item requires a technical fix e.g. a water leak or failed light fitting, the incident is escalated by raising a CM Work Order (WO) in the Computerised Maintenance Management System (CMMS).

Equipment running issues or breakdowns are raised directly as CM WOs in the CMMS by Facilities staff.

In terms of PM, there are 903 schedules across the Ervia office portfolio. These in turn generate multiples of weekly and monthly PM WOs.

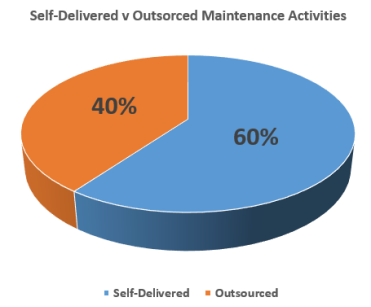

The following charts break out the annual mix of maintenance activities by types, quantities and whether they are actioned through self-delivery or out-sourcing.

Figure 2: Quantities of Maintenance Activities by Type

Figure 2 shows the various types and approximate quantities of Maintenance Activities that are raised annually within the Ervia Facilities department.

Figure 3: Self Delivered v Outsourced Maintenance Activities

Figure 3 shows the percentage split in terms of delivery of Maintenance Activities.

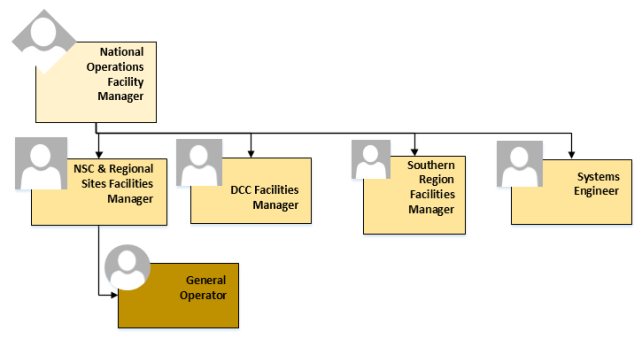

Figure 4: Ervia Organisation Chart

Figure 4 displays the Ervia maintenance team Organisation Chart.

The 6 employees in the above chart are the Ervia staff in the Facilities department that have responsibility over the maintenance function. There are other staff in the department but we will only consider the above for this report.

The Systems Engineer, despite the implication in the job title, sits at a middle management level and is considered to be a peer of the Facilities Managers.

The General Operator (GO) stands out as being the only person of that rank that is a member of the Ervia team. The GO in question is a long serving staff member of Gas Networks Ireland and chose not to transfer to OCS when the first IFM contract was awarded. This situation presents a complication as the GO will not take direction from OCS staff and instead all orders have to be channelled through the NSC & Regional Sites Facilities Manager.

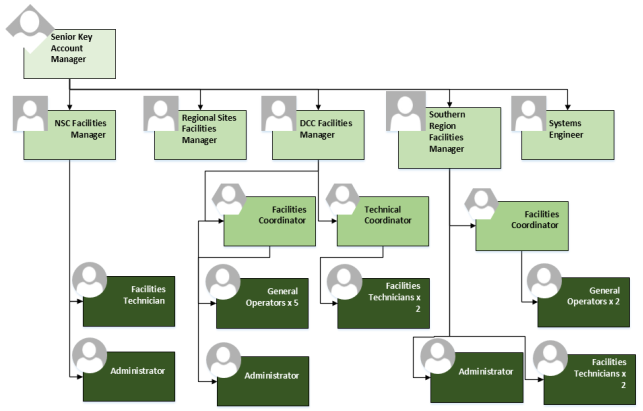

Figure 5: OCS Organisation Chart

Figure 5 displays the OCS maintenance team Organisation Chart (based on the Ervia FM contract).

The 24 employees in the above chart are the OCS staff that are embedded on the Ervia IFM contract. All roles are subject to Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) (TUPE) regulations and will move to the new service provider should OCS not be successful in their efforts at contract renewal in 2018.

As with Ervia, the OCS Systems Engineer sits at a middle management level and is considered to be a peer of the Facilities Managers.

We can see from the above chart that the DCC Facilities Manager has a far bigger team at his disposal than the other mangers. This is because over half of the Ervia office staff are situated in the buildings within his remit.

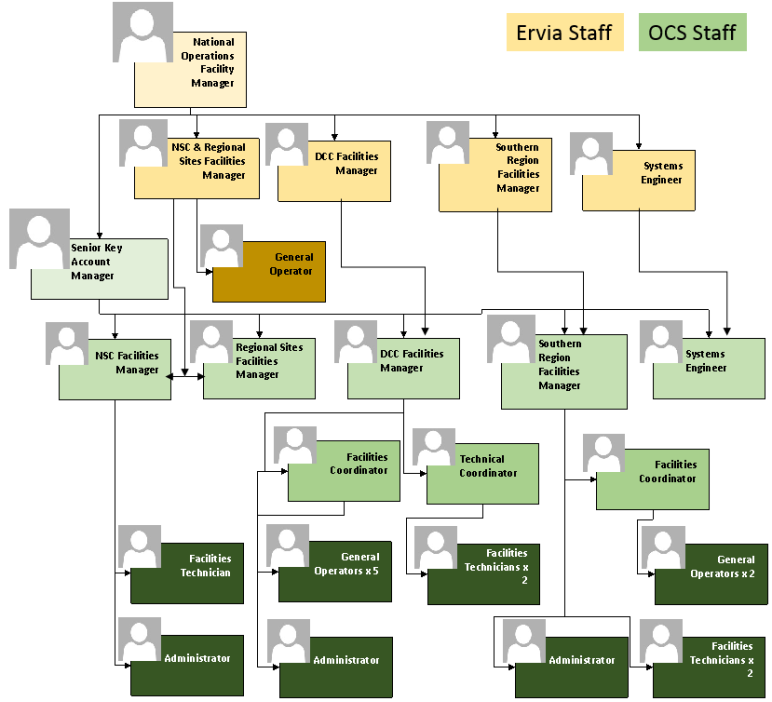

In isolation, the Ervia and OCS organisation charts seem to represent an acceptable scenario. However when we combine them in Figure 6, we can instantly see that improvement steps need to be taken. There is obvious duplication of roles at Facilities Manager and Systems Engineer level. Dual reporting is also apparent with the OCS Facilities Managers and Systems Engineers having to ‘answer’ to both Ervia and OCS management.

Figure 6: Combined Ervia and OCS Organisation Chart

Figure 6 displays the Combined Ervia and OCS maintenance team Organisation Chart.

The above Organisation Chart may in parts seem both confusing and utterly unbelievable, especially when linking the OCS structure to Ervia. The aim of Table 2 is to further explain the duality of the reporting structure.

Table 2: OCS to Ervia Reporting Structure

|

|

Report To |

|

OCS Senior Key Account Manager |

Ervia National Facilities Operations Manager |

|

NSC Facilities Manager |

OCS Senior Key Account Manager |

|

Ervia NSC & Regional Sites Facilities Manager |

|

|

Regional Sites Facilities Manager |

OCS Senior Key Account Manager |

|

Ervia NSC & Regional Sites Facilities Manager |

|

|

DCC Facilities Manager |

OCS Senior Key Account Manager |

|

Ervia DCC Facilities Manager |

|

|

Southern Region Facilities Manager |

OCS Senior Key Account Manager |

|

Ervia Southern Region Facilities Manager |

|

|

Systems Engineer |

OCS Senior Key Account Manager |

|

Ervia Systems Engineer |

The most remarkable fact about this combined structure is that, somehow, it actually works. It can be safely said that it is both collaborative and operationally effective. Even though each mid-level manager has two persons to report to, somehow the contract proceeds with very little conflict to the extent that at times the relationship between Ervia and OCS has been described as ‘incestuous’!

However it is clear that it could not be effective from a cost perspective. For instance there are more managers than technicians. The superfluous layer of middle management will be the initial focus when it comes to suggesting improvements in cost effectiveness.

From the above we can also conclude, with certainty, that operational efficiency requires improvement. For example, if any of the OCS Facilities Managers or Systems Engineer needs approval to take an action, they will have to seek this from two persons. This can turn into a game of ping-pong as the approving managers may not initially agree on the same course of action. Usually in this scenario, the Ervia approving manager’s opinion will prevail due to the ‘customer is always right’ philosophy.

The structure as portrayed in Figure 4 is not unknown in the Irish semi-state/public sectors where there have long been accusations by print and broadcast media of wasteful spending (McConnell, 2015).

It is a fair question to ask as to how this situation developed. Among the reasons are:

- As Ervia came into being by virtue of decisions made at government level, the result was the virtual overnight creation of the biggest utility company in Ireland that had rapidly expanding responsibilities.

- Employees transferred from the Gas Networks Ireland Facilities department to Ervia without an assessment being made on whether they were required or not.

- Because of the above, it was more pressing at the time to simply get a Facilities department up and running without considering the most efficient means of doing so.

6.1 Phase 1 Development – Losing Fat in the Midsection

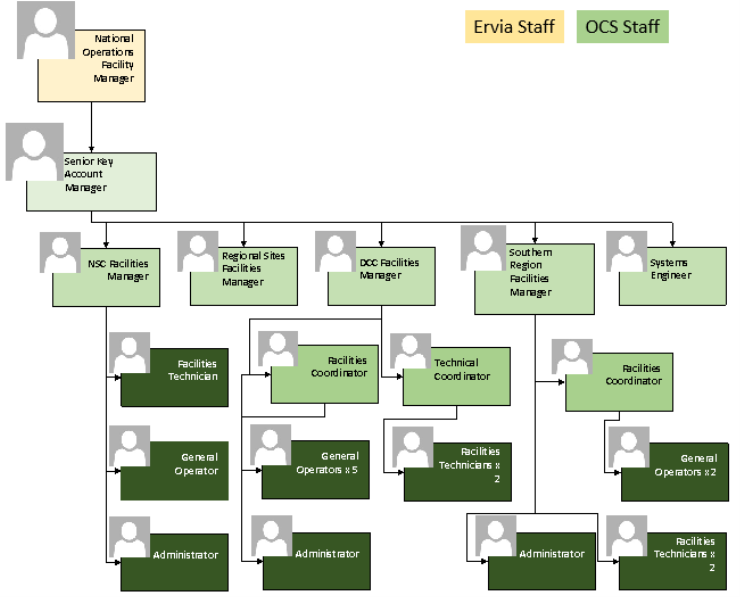

Figure 7: Proposed Phase 1 Combined Ervia and OCS Organisation Chart

Figure 7 displays the Proposed Combined Ervia and OCS maintenance team Organisation Chart at the Phase 1 level of development.

We can see in Figure 7 that the structure looks less convoluted and is starting to develop a balance. The first task in this development will be to remove the duplicate layer of middle management. The second task will be to change who the Ervia GO reports to.

The following two actions will have to be taken to enable this:

- The Ervia Facilities Managers and Systems Engineer roles will have to be made redundant.

- The Ervia GO will have to transfer to OCS.

6.2 Phase 2 Development – The Rise of the Systems Engineer

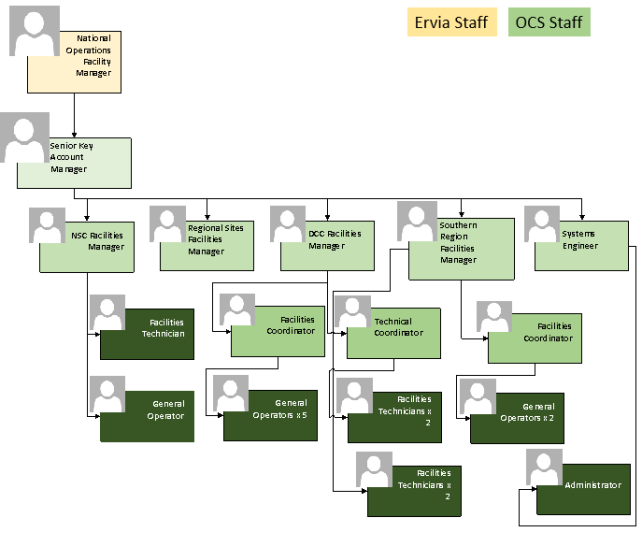

Figure 8: Proposed Phase 2 Combined Ervia and OCS Organisation Chart

Figure 8 displays the Proposed Combined Ervia and OCS maintenance team Organisation Chart at the Phase 2 level of development.

We can see in Figure 8 that the maintenance organisation now looks to be much more ordered and has a well-balanced structure. Duplication of roles and dual reporting has been removed.

To enable this change, the role of the Systems Engineer will have to be considerably expanded. Up to this point the focus of this role was to collate asset data, install both a CMMS and an incident management system.

The Systems Engineer can now fully take the reins regarding a systematic approach to improving work management. To do this, the support of an administrator will be required once the system becomes operational. Once fully realised, this system will negate the need for the 3 administrators that report to the Facilities managers.

The reduction in administrators is possible because the new CMMS is configured for paperless WOs and much increased automation of reporting. The maintenance staff will now carry tablet computers to execute completion of WOs.

From this point onwards, the Systems Engineer’s office will become the nerve centre of maintenance activities for the Facilities department with the following items featured prominently:

- Planning and scheduling of maintenance activities will be managed from there in conjunction with the site based technical staff. This is detailed further in Section 7.

- The CMMS will be fully managed from there with PM WOs for all sites generated by the administrator on a weekly basis.

- Reports from the Incident Management systems and CMMS will also be compiled at this office. These will be channelled directly to senior management at OCS and Ervia.

- The Systems Engineer will chair a monthly meeting with the Facilities Managers and cover upcoming works and resources requirements/availability.

- Implementation of work prioritisation. Again this is drilled into further in Section 7.

6.3 Phase 3 Development – Breaking Down the Barriers

Something that is not visible from the above organisation charts is the discreet walls that exist between the various site teams. It could even be said that they operate almost as autonomous groups.

It is hoped that Systems Engineer’s increasing prominence will organically bring about change in this area and pull the teams together. There is much to be gained by sharing both knowledge and resources when possible. For instance one of the Facilities Technicians in the Dublin City Centre (DCC) sites is a qualified refrigeration engineer, he could provide technical assistance and advice regarding air conditioning equipment to the other sites.

In the longer term, once the maintenance organisation has settled following the period of enforced change, consideration should be given to reviewing how maintenance activities are performed. There are likely to be opportunities for improvement of cost effectiveness in this area also.

7.1 Ranking Index for Maintenance Expenditure (RIME)

It is envisaged that a system for prioritisation of maintenance activities will be introduced to the Facilities organisation. In RIME, expenditure refers to both time and cost.

RIME works by assigning scores for the following factors:

- Asset criticality.

- WO criticality.

- Amount of time a WO is open.

These scores are then multiplied which will, if the system is configured properly, ensure the most important work gets the highest total score.

The newly installed CMMS at Ervia supports RIME and automatically provides total scores for WOs. This will allow maintenance staff to see a list of activities assigned to them in high-to-low order of priority.

7.2 Developing the Planning Function

Sound planning practices are essential for any maintenance organisation and implementation of such is considered best practice.

In the Ervia Facilities department, the OCS Systems Engineer will lead the charge in rolling out planning across the maintenance team. As detailed earlier, The Systems Engineer will chair a monthly meeting with the Facilities Managers and work planning will take centre stage at this meeting.

A further aim of these meetings will be to knock down the discreet walls that exist between the different site teams. There should be opportunities to share both learning and indeed resources but proper lines of communication need to be established first.

The changes that can be implemented have now been suggested but what are they going to achieve in terms of improving cost effectiveness? The bullet points below will attempt to quantify expected savings:

- Removing Layer of Middle Management

- The Facilities Managers and System Engineer each come at a cost of €100,000 to Ervia. Removing the 4 as proposed, will bring a saving of €400,000.

- Reducing Number of Administrators

- Each administrator comes at a cost of €50,000 to Ervia. Removing 3 as proposed, while transferring 1 to support the Systems Engineer will bring a saving of €100,000.

- Introducing RIME

- Any savings to be generated here are difficult to quantify at this juncture but a system for prioritising work can only be a good thing and will surely result in at least some cost avoidance by getting the important work done at the right time.

- Developing Work Planning

- Again any savings garnered by taking this measure are difficult to quantify at present but will help ensure maintenance best practice is followed.

- It is worth noting however that the rule of thumb in industry is unplanned maintenance can cost at least 3 times as much as planned maintenance (Strawn, n.d.).

- Points to note

- In terms of staff resources, savings are calculated based on the cost to Ervia which takes into account such items as Pay Related Social Insurance and Management Fees charged by OCS as part of the IFM contract. Detailed resource costs are tabulated in Appendix A.

- It must be noted that only the savings in relation to reducing the number of administrators will impact the IFM contract costs. The removal of the Ervia middle management does not impact the IFM contract value.

To quote Jack Welch (2001), the person regarded by many as the greatest company leader of his generation “Change before you have to”.

Ervia needs to get its house in order if there are external changes introduced such as reduced budgets and/or an increase in the number of sites to maintain.

At present there is much volatility in Irish political circles with funding of public/semi state companies a constant hot topic. Ervia could be faced with the possibility of having its funding slashed at government level and in tough times the maintenance department of any organisation is often seen as a soft target.

Since there is an IFM contract renewal coming at the beginning of 2018, this could be used as an opportunity to begin the implementation of changes. It would mean that the proposed structures could be built in to the new contract which would avoid having to use the change control process that applies during contract ‘run time’.

Again, to draw from the famed former head of General Electric (GE), Jack Welch, “Willingness to change is a strength, even if it means plunging part of the company into total confusion for a while” (Slater, 1998).

Let’s consider, in the following sub-sections, the two main points of impact as a result of implementing the proposed changes. We will also consider on how to mitigate the effects.

10.1 Staff Reductions and Transfers

These decisions will not be easy to implement. There will be considerable resistance from the Ervia Facilities Managers and Systems Engineer. Should the situation become intractable, it may be necessary to remove the layer of middle management from OCS instead. The Ervia staff would then transfer to OCS and report to the Senior Key Account Manager. The path of least resistance may have to be followed. It could well turn out that the Facilities Managers and Systems Engineer team are made up out of a combination of OCS and former Ervia staff that have transferred.

The Ervia GO may take umbrage at having to transfer to OCS. The last time these attempts were made resulted in failure.

The shakeup at administration level could also cause rancour. Because the Systems Engineer is based in one of the Cork offices, the administrator that supports this role will likely come as a transfer from the Southern Regional Sites Facilities Manager’s team. The two Dublin based administrators will have to be made redundant.

Willing to make changes is one thing but successfully managing the change will be crucial. A rocky road will have to be travelled with the possibility of staff morale taking a hit. Potential resentment from the soon-to-be unemployed staff towards retained staff is also likely during the transition phase.

The strength that Welch speaks of will have to come from senior management in both Ervia and OCS. Considerable resolve will have to be displayed when communicating to employees that they no longer have a job. A silver lining can be added to the cloud by ensuring favourable severance packages for those made redundant and committing to TUPE regulations for any employee that transfers to OCS.

10.2 Introduction of Work Management Systems

It could be perceived by the Facilities Mangers that a power grab is taking place by the Systems Engineer. The onus will be on the Senior Key Account Manager to sell the benefits of the changes in practice.

Over time, the benefits should then start to become self-evident as management of work improves, shared learnings disseminate and client contentment increases as a result of a better run contract.

10.3 Industrial Relations Concerns

The changes proposed above will not be encumbered by IR action. Neither Ervia nor OCS staff are union affiliated so as long as the employee’s legally held rights are observed, there should be no issue.

The Facilities department could be presented with a dramatic widening of its scope in the next number of years. It is envisaged that Ervia, through Irish Water, will eventually absorb all county and city council staff that are currently involved in maintaining the water services infrastructure. This could involve the transfer of up to an additional 2,500 staff. The knock-on effects for the maintenance team within the Facilities department would be considerable. The multitude of premises that house all these employees would then be in scope for upkeep and repair.

There is currently a team charged with developing a plan to allow for the transfer of these staff and premises to the Ervia parent utility group. The Water Industry Operating Framework (WIOF) will contain the new obligations that the Facilities department will be required to meet.

Both Ervia and OCS, should they retain the IFM contract, will have to ready themselves for the huge challenges coming down the tracks. The best way to achieve this is to allow for scalability in the systems that are designed and built.

While extra staff will no doubt have to be recruited, duplication of roles as per the current situation will have to be avoided. The time is right at present to ensure a solid foundation is laid to accommodate this forecasted expansion.

In the predicted scenario, additional costs are going to be incurred. The measures proposed in this report, if implemented, will serve to keep these extra costs to a minimum.

At a higher level, there are additional changes that could be made to improve cost effectiveness. As mentioned earlier, the current IFM contract with OCS falls under the Cost Plus model.

Detailed below is an alternative to this contract type known as Fixed Price/Output Based. The author of this report has previous experience of this type of IFM contract. The bullet points below show advantages and potential shortcomings:

- Headline Information (based on example):

- 10% up-front savings guaranteed over costs incurred by client to deliver maintenance.

- Built in ‘glide path’ which consisted of a 1% year-on-year reduction in cost of overall contract.

- IFM absorbed costs of up to €5,000 per breakdown.

- IFM had full authority on staff numbers and how maintenance was delivered.

- Contract was ‘5 + 5’ i.e. initial duration of 5 years with option by client to extend for a further 5 years without re-tendering.

- Advantages:

- Costs for client are tied down.

- Incentive for IFM provider to implement cost effective maintenance.

- Disadvantages:

- Instead of what Emmet and Wheelhouse (2011) describe as collaborative, the relationship can instead become transactional and often even adversarial.

- Risk that IFM may cut corners regarding maintenance in order to deliver on-budget.

- ‘Race to the bottom’ mentality can pervade during tendering where prospective service providers will submit unrealistically low pricing in order to win the contract.

- Requirements to make it work:

- Watertight contract with relevant Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to accurately monitor IFM contract compliance.

- Condition of equipment in contract scope needs to be thoroughly evaluated during the tender process and the client must have an ‘open book’ policy regarding historical failure data.

- Enough financial head room in the contract to allow the IFM provider to make a profit. If this is not present, the contract will inevitably collapse with possible adverse consequences for business continuity.

In the example above, the contract was terminated by the client after 2 years due to poor service delivery and repeated KPI failures. The main cause of this, in the author’s opinion, would be that the IFM provider submitted such a low price at tendering that they could not meet the agreed contract conditions while generating a profit.

To open the conclusion, it’s fair to say the above analysis may seem cold but it is approached from a business perspective with a view to achieving a sustainable maintenance organisation that is capable of surviving more stringent cost controls that may lie ahead.

On the face of it, it would seem that the maintenance organisation within the Ervia Facilities department is ripe for change. And to sustain the analogy, there may even be some low hanging fruit!

Listed below are the positives that will come with introducing change:

- Staff reductions alone will bring €500,000 in savings and if all goes according to plan, there will no reduction in the level of service to the wider organisation.

- The introduction of advanced Work Management systems should also improve cost effectiveness but it’s hard to quantify the level of such at present.

- Ultimately what is required is to achieve the same level of performance for reduced expenditure or in the utopian situation, an increased level of performance for reduced expenditure.

- The latter scenario is referred to the “genius of the ‘and'” (Collins & Porras, 1994). For the Ervia Facilities department, it means that they should strive towards improving performance and seek a reduction in maintenance costs.

- Introducing Work Management systems should give the performance boost while reducing staff will provide savings.

That’s the easy bit done! Now, how can the changes be made without excessively adverse workplace relations developing? There are a lot of pot holes that must be carefully steered around and these things are far easier to write about than actually implement.

Listed below are the potential downsides:

- Contract renewal time was stated earlier as being an ideal opportunity to ring the changes. The risks here are that too many changes are being made in a short space of time. It might be prudent to phase the changes over 6 months from the beginning of the new IFM contract in 2018.

- Jack Welch advised us to make changes before we are forced into doing so (2001). But Ervia and OCS staff may well not be as pliable as GE employees when it comes to such upheaval. Luckily none of the staff involved are union affiliated.

- Another possible issue is that when making staff redundant by role, we are not taking into consideration that these could be higher performing than the staff being retained.

A seemingly obvious omission from this report is inventory management and any measures the maintenance department could take in this area that would improve department cost effectiveness. The reason for this omission is that because of the nature of Facilities Management, inventory does not play a major part. Consumables such as lighting lamps and other miscellaneous electrical equipment are stored on site. Equipment spare parts are supplied by sub-contractors in the event of PM or CM activity.

To finally conclude, let’s ask 3 questions:

- Can Ervia, in partnership with OCS, implement the proposed changes?

- Will it be difficult to get the changes over the line?

- Should the changes be made?

It is the author’s opinion that the answer to all of the above is an emphatic ‘Yes’.

Collins, J. & Porras, J. I., 1994. Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. 1st ed. s.l.:HarperBusiness.

Emmet, S. & Wheelhouse, P., 2011. Excellence in Maintenance Management. s.l.:Cambridge Academic.

McConnell, D., 2015. Our shameful legacy of waste and incompetence. [Online]

Available at: http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/our-shameful-legacy-of-waste-and-incompetence-30953852.html

[Accessed 7 March 2017].

Moubray, J., 1991. Reliability-centered Maintenance. s.l.:Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd..

Slater, R., 1998. Jack Welch & The G.E. Way: Management Insights and Leadership Secrets of the Legendary CEO. 1 edition ed. s.l.:McGraw-Hill.

Strawn, T., n.d.. Maintenance Planning, Scheduling Deliver To The Bottom Line. [Online]

Available at: http://www.marshallinstitute.com/default.asp?Page=Maintenance_Resources&Area=Articles&ARTID=MPSdelivertobottomline

[Accessed 6 March 2017].

Welch, J., 2001. Jack Straight From The Gut. 1st ed. s.l.:Grand Central Publishing.

15.1 Appendix A

Table 3: Resource Costs

|

Employer |

Role |

Cost to Business |

Quantity |

Total |

|

Ervia |

Facilities Manager |

€100,000 |

4 |

€400,000 |

|

Ervia |

Systems Engineer |

€100,000 |

1 |

€100,000 |

|

Ervia |

General Operator |

€45,000 |

1 |

€45,000 |

|

OCS |

Facilities Manager |

€100,000 |

4 |

€400,000 |

|

OCS |

Systems Engineer |

€100,000 |

1 |

€80,000 |

|

OCS |

Technical Coordinator |

€70,000 |

1 |

€70,000 |

|

OCS |

Facilities Coordinator |

€70,000 |

2 |

€140,000 |

|

OCS |

Facilities Technician |

€60,000 |

5 |

€300,000 |

|

OCS |

Administrator |

€50,000 |

3 |

€150,000 |

|

OCS |

General Operator |

€45,000 |

8 |

€360,000 |

Note: Only Resources that are considered as part of the plan to improve cost effectiveness are considered in the above table.

Collins, J. & Porras, J. I., 1994. Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. 1st ed. s.l.:HarperBusiness.

Emmet, S. & Wheelhouse, P., 2011. Excellence in Maintenance Management. s.l.:Cambridge Academic.

McConnell, D., 2015. Our shameful legacy of waste and incompetence. [Online]

Available at: http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/our-shameful-legacy-of-waste-and-incompetence-30953852.html

[Accessed 7 March 2017].

Moubray, J., 1991. Reliability-centered Maintenance. s.l.:Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd..

Slater, R., 1998. Jack Welch & The G.E. Way: Management Insights and Leadership Secrets of the Legendary CEO. 1 edition ed. s.l.:McGraw-Hill.

Strawn, T., n.d.. Maintenance Planning, Scheduling Deliver To The Bottom Line. [Online]

Available at: http://www.marshallinstitute.com/default.asp?Page=Maintenance_Resources&Area=Articles&ARTID=MPSdelivertobottomline

[Accessed 6 March 2017].

Welch, J., 2001. Jack Straight From The Gut. 1st ed. s.l.:Grand Central Publishing.

OCS Staff Members

OCS Staff Members