Disruptive Innovation Theory in the Accommodation Sector

Â

Â

Traditionally within the accommodation sector of the hospitality industry prospective guests rented rooms from recognised businesses like hotels. In recent years, technological advancements have led to the emergence of peer-to- peer platforms, collectively known as the “sharing economy”. This has disrupted the model by providing an online marketplace that allows individuals to rent available spaces to individuals looking for accommodation in a region or area. Whilst peer-to-peer accommodation is the basic model underpinning the traditional B&B market, it was limited because hosts found it difficult to make their accommodation offerings known to potential guests, in addition, they also faced challenges establishing trust. Technological advancements like the Web 2.0 internet technologies allow suppliers to list their offerings cheaply and easily and also make it easy for consumers to search those listings and find reviews of the properties, thus establishing trust.

Considering major hotel chains like Hyatt Hotels, Wyndham Hotels, and The InterContinental Hotels Group have recently invested in peer-to-peer accommodation sharing platforms like Onefinestay, LoveHomeSwap, and Stay.com. The board of management of The McGettigan Hotel Group, an Irish, independent, family-owned hotel group offering accommodation in hotels in Cork, Donegal, Dublin, Limerick, Wexford and Wicklow have commissioned this report to look at disruptive innovation, the effect of peer-to-peer sharing on the hotel industry and to assess what a hotel chain can do to respond to the threat of the sharing economy.

The hotel sector in Ireland has experienced dramatic changes since the start of the economic downturn in 2008. This change is evident in the decline in Revenue per Available Room (RevPAR), from a high of €68 in 2007 to a low of €43, 2010 showed further recovery to €54 in 2014 (Grant Thornton, 2015). Dublin hotels are expected to top the 2017 RevPAR growth league table per PwC’s European cities hotel forecast for 2016 and 2017 (PWC, 2016).

Â

A lot of the literature on innovation – particularly business model innovation – originates from the work of Clayton Christensen. Christensen is Professor of Enterprise at Harvard Business School and is regarded as one of the world’s top experts on innovation and growth. He was also named as the most influential business thinker in the world (Christensen, 2017a). “Disruptive innovation theory has had a profound effect on the research of dynamics between established incumbents and disruptive entrants” (Gerwe and Silva, 2016). “Disruption” in this case describes a situation where an organisation with access to less resources is able to successfully challenge the established incumbent business (Christensen, Raynor and McDonald, 2015).

In his first book, the Innovators Dilemma, Christensen (1997) outlined two forms of innovation. The first form of innovation alters or changes a product/service that was traditionally either too expensive too or complicated to use and therefore only people with a lot of money or skill could own or use. For example, in the early 1900’s the hotel industry served the wealthiest members of society, as they were the ones with the time and financial resources to pursue leisure activities and use their products/services. In the 1960’s budget hotel chains like The Holiday Inn entered the market to serve the needs of people at the lower end of the market. This was considered a disruptive innovation using Christensen’s model as it transformed the product/service making it more affordable and simple, and something that a larger group of people could use. Disruptive innovation “describes a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up market, eventually displacing established competitors.” (Christensen, 2017b).

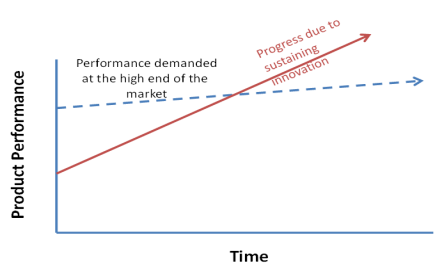

The Innovator’s Solution (Christensen and Raynor, 2003) takes up where Christensen left off in his first book. The following two exhibits explain Christensen and Raynor’s (2003) disruptive innovation process. Figure 1 (page 3) depicts a competitive market where the product/service providers exists to serve a market that is willing to purchase a product/service at the higher level and have the maximum profit potential. Maintaining these customers means providers only innovate to meet the increasing demands of their most profitable customers or to remain competitive with one another.

Figure 1 Traditional Organisation (Christensen and Raynor, 2003)

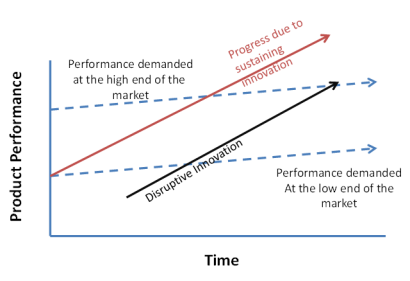

When organisations chose to adopt this short-sighted focus on maintaining their current customers, they risk competition from those entering the market with more affordable, inferior products (figure 2). Often the existing firms chose not to contest the new entrant, as their focus is generally on the lower and less profitable end of the market. However, once these organisations gain a foothold they begin the process of innovating. Traditional organisations tend to innovate faster than customers need, eventually producing a product/service that is either too expensive or too superior, relative to the alternatives. By that time, the low-cost option has risen to the level of being good enough, customers chose to move to it and the providers at the upper end of the market are at that point either unwilling or unable to compete using their current business model.

Figure 2 Disruptive Innovation (Christensen and Raynor, 2003)

By way of an illustration consider the European airline industry in the mid-1990’s. Flagship carries like Aer Lingus, British Airways and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines found themselves under attack from recent entrants to the market like Ryanair and Easy Jet. The flagship carriers mistakenly assumed that the new entrants would have to adopt the high-cost low-margin business model of the industry at that time, thus creating a barrier to direct competition. However, the new entrants came to market with a low-cost, point-to-point, no-frills strategy. The product and level of service they offered at the time could never rival that of the flagship carriers, what they failed to see is that it did not have to. In essence, when the new entrants had achieved success serving the smaller markets with lower margins, they began the process of innovating and through continuous improvement they became good enough for an increasing number of customers, thus capturing more of the European market. Their affordability combined with an efficient service created a value proposition that appealed to many travellers and one that that the flagship carriers could not easily match, in part due to their existing business model and practices. Demonstrating how the disruptive innovation of these no-frills start-ups doesn’t involve any ground-breaking technology or processes, it is achieved by simply designing and operating a business model that can a product/service that is good enough at an acceptable price point. Again, the key take-away is that companies tend to innovate faster than their customers need, inviting competition from the lower end of the market that has the potential to move upmarket overtime.

Â

4.1 The Sharing Economy

PWC (2016 a) identified several “megatrends” that are changing our professional and personal life. The “sharing economy” is amongst them. The sharing economy is defined as “an economic model based on sharing underutilized assets from spaces to skills to stuff for monetary or non-monetary benefits” (Botsman, 2013). The sharing economy reflects the increase in virtual marketplaces that facilitate peer-to-peer transactions on a large scale via online platforms (Zervas, et al., 2015). “This emerging paradigm is already disruptive to the conventional company-driven economic paradigm as evidenced by the large number of peer-to-peer based services that mushroom in a wide range of economic sectors” (Avital et al., 2014). In recent years, the sharing economy has growing exponentially. PWC’s (2016 a) analysis suggests that global revenues for the sharing economy will exceed €290bn by the year 2020.

A PWC (2015) report on the sharing economy said that as a model, these core pillars distinguish the sharing economy:

Digital platforms that connect spare capacity and demand

Sharing economy business models are hosted through digital platforms that allow for precise, real-time measurement of spare capacity, they also connect it with those who need it.

- Airbnb matches spare rooms and residences with travellers in need of lodging

Transactions that offer access over ownership

Access can come in several forms, but all are rooted in the ability to realise more choice while mitigating the costs associated with ownership for example renting, lending, reselling

More collaborative forms of consumption

Consumers who use the sharing economy are often more comfortable with transactions that involve deeper social interactions than traditional methods:

- Airbnb provides tourists with the means to connect with local hosts

Branded experiences that drive emotional connection

In recent years, the value of a brand is often linked to the social connections it fosters. Within the sharing economy, the experience is often designed to promote an emotional connection, thus building confidence with the consumer.

4.2 Airbnb

The most significant recent transformation within the accommodation sector started in 2007 when two university graduates decided to rent out vacant space in their apartment to delegates attending a conference in the form of three air mattresses on the floor of their San Francisco apartment. They used a simple website to advertise this unused space as an ‘Air Bed & Breakfast’ to delegates seeking to avoid high hotel prices. The success of this initial letting led them to believe they had a business idea, at that point they recruited another friend and build a website to allow other people to advertise their unused spaces as shared accommodation. In 2009 the website relaunched as Airbnb.com, and expanded to include the rental of entire residences (Carson, 2016).

Airbnb is the poster child of the sharing economy having been a first mover in the peer-to-peer accommodation market. Airbnb was valued at $25.5 billion in June 2015 (Statista, 2017) and reported revenues of $900 million in 2016 (Taylor, 2017). The company provides a platform that allows users to rent out their spare rooms, vacant homes or unutilised space to strangers. In 2015 it has in excess of 10 million stays on its platform (McAlone, 2015) and it currently has more than 3 million listings in in 191 countries (Airbnb, 2017). The Fast Company are quoted in The Economist (2015) as saying that Airbnb would “usurp the InterContinental Hotels Group and Hilton Worldwide as the world’s largest hotel chain – without owning a single hotel.”

To fit Christensen & Raynor’s (2003) disruptive innovation model the product/service must have an innovative business model that targets people at the lower end of the market. The use of technological advancements like Web 2.0 technologies to enable peer-to peer sharing have facilitated Airbnb’s innovative business model, meeting the first part of the criteria. Airbnb meet the second as their products are lacking in many of the areas that are considered important to guests when choosing hotel accommodation, aspects like service quality, guest experience, brand reputation, security and facilities.

As discussed earlier disruptive products/services lack some of the key attributes in their product category, however, they are also often cheaper and offer other benefits. As is the case with Airbnb, in general their accommodation is cheaper than traditional hotels, in addition, their product offerings introduce some additional benefits like staying in a residential area with the use of a full house.

Cost can be a major factor for tourists when making decisions about what accommodation to book. Airbnb’s relatively low cost is a factor, it is enabled because hosts can price their unused spaces very competitively as their fixed costs (electricity and mortgage) are sunk costs. In addition, hosts have lower labour costs as they often provide labour themselves. They are also less price sensitive as they are generally not dependent on their Airbnb revenue. In 2011 Ron Lieber of The New York Times stayed in two one-room studios, one one-bedroom apartment and the second bedroom of a two-bedroom unit over five nights in Lower Manhattan, he had booked all of his accommodation through Airbnb. He spent a total of $922 over five nights, $724 less than the $1,646 that comparable hotels in the same area would have cost on Expedia (Lieber, 2011).

Research conducted by Guttentag (2013) demonstrates Airbnb’s relatively low costs. Table 1 (see appendix), compares Airbnb costs with hotel and hostel costs in six destinations. “Airbnb’s mean rates are reasonably competitive, median rates slightly more so. For example, the median Airbnb rates for an entire home/apartment are generally less than those of four and five-star hotels, and the median Airbnb rates for a private room are roughly comparable to those of one and two-star hotels” (Guttentag, 2013). Further analysis shows that if you assess the ten cheapest rates across all three accommodation types, Airbnb shows significant cost savings. It is possible to rent an entire property for the same price as a two-star hotel or a private room for the same price as a hostel.

In addition to the cost benefits, Airbnb’s offerings differ in that they provide the benefits of staying in a normal residence, like having the use of a kitchen, access to a washing machine and tumble dryer, and in some cases hosts can provide useful local information. Guests get the opportunity to have local immersive experience by living like a local, interacting with local people, and possibly staying in a ‘non-touristy’ area. This fits with MacCannell’s (1973) assessment that tourists wanted to access ‘back regions’. He highlighted their “desire to share in the real life of the places visited, or at least to see that life as it is really lived”, noting that “tourists try to enter back regions of the places they visit because these regions are associated with intimacy of relations and authenticity of experiences”.

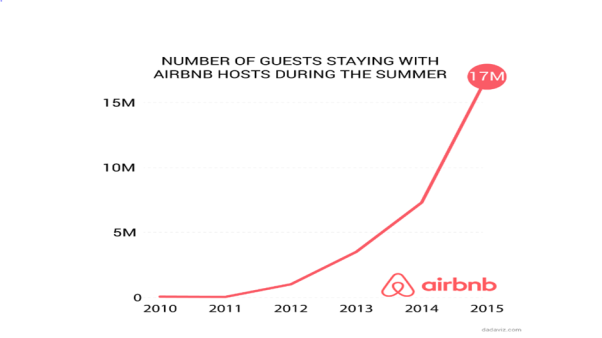

Disruptive innovation theory suggests a disruptive product/service should serve the lower end of the market and as such be limited in its initial popularity, it should then move into the mainstream market and grow. Figure 3 shows that this pattern describes Airbnb’s growth, in the early years it wasn’t very popular, however, it experienced explosive growth over the past few years.

Figure 3 Airbnb Growth (McAlone, 2015)

4.2.1 Impact on the Hotel Industry

The additional supply Airbnb brings to the market is expected to negatively impact hotel rates and revenues (Jordan, 2015). This is supported by Merril Lynch, who concluded that in 2017 oversupply will negatively affect hotel business values (Huston, 2015). Zervas et al. (2014) quantified the impact: they estimate a 13 per cent decrease in room revenue for Austin and go on to say that for every 10 per cent increase in Airbnb listings in Texas hotels could expect to see a 0.35 per cent decrease in monthly room revenue. They also observed that lower-end hotels and hotels without business facilities were worst affected.

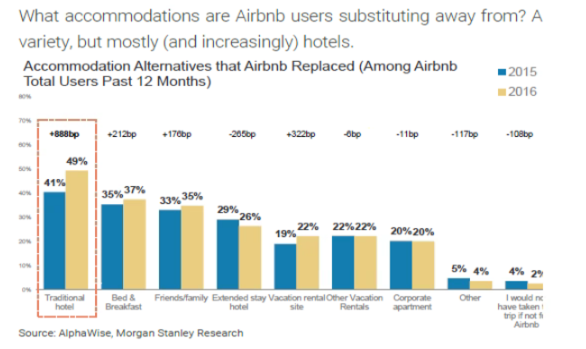

Morgan Stanley (2016) surveyed more than 4,000 consumers from the U.S., U.K., France and Germany to gauge Airbnb’s growth, but also assess where demand for the service lay. They concluded that hotels are going to take the bigger hit. “While still small, we believe Airbnb has been almost double the threat to hotels in 2016 than previously believed, and the threat is growing.”

Figure 4 User Substitutions (Source: Morgan Stanley, 2016)

4.2.2 Potential Threats to Airbnb’s Future Growth

The illegality of Airbnb rentals and the increasing attention they have been receiving from lawmakers across the world undoubtedly pose a threat to their long-term success. There is pressure for Governments to force Airbnb to rein in illegal rentals. Some cities prohibit short-term renting without special permits. For example, San Francisco prohibits unlicensed rentals of fewer than 30 days and New York enacted a similar law recently (Benner, 2016). As recently as March 13th 2017 Dublin City Council expressed concern that Airbnb had 6,729 listings in Dublin and there was an absence of regulation in the sector (Pope, 2017). At present Dublin’s housing market is experiencing a limited housing supply, short-term rentals may be negatively impacting the housing market.

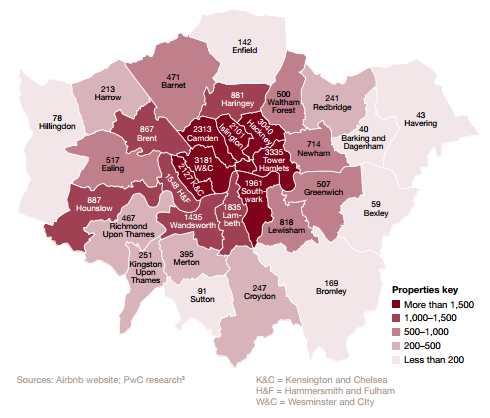

PWC (2016) conducted research on Airbnb’s presence in London to ascertain its impact on hotels in the region. On July 27th 2015 airbnb.co.uk showed approximately 31,000 listings available in the London region. In 2014 alone the Daily Telegraph reported that listings in London had increased by 87% (Davidson, 2015).

Airbnb provides tourists with a variety of different accommodation options, this has increased competition for hoteliers in several regions. In late 2014 research conducted by PWC showed that 10% of hoteliers were experiencing negative demand because of Airbnb’s market offerings.

PWC (2016) looked at apartment listings on airbnb.co.uk within the London region to assess the impact on the London market. Figure 4 shows apartment listing by borough, darker shades indicate a higher concentration of listings within that borough. It is worth noting that on Airbnb a single property can potentially be listed multiple times – as two separately bookable rooms.

Figure 5 Airbnb Heatmap Listings by Borough (Source: PWC, 2015)

PWC sampled six boroughs (three inner and three outer) and concluded that the majority of listings were comprised of private rooms, Westminster and the City were exceptions where almost 67% of listings comprised of entire houses – most likely run as commercial enterprises and competing directly with branded hotels. On the supply side individuals who listed private rooms to supplement their income could potentially be more disruptive as they were less price sensitive. In addition, the number of private rooms far outweighs the number of second homes. This “hidden capacity” was hard to access and represented risk due to increased supply.

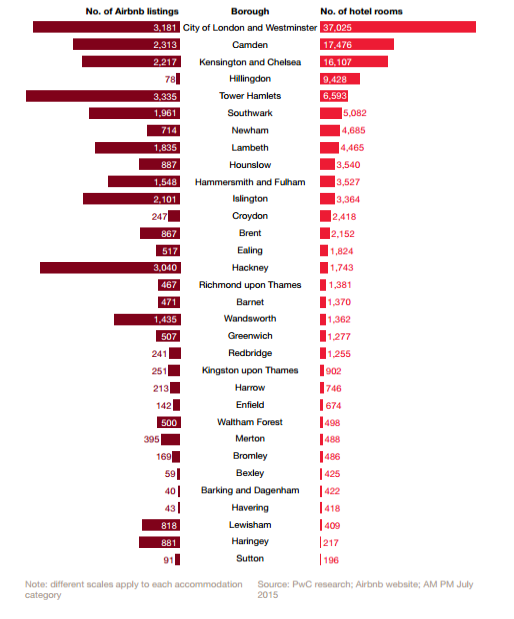

Central boroughs were popular as they were near tourist attractions and amenities. Outer central boroughs, although a significant distance from central London, offered better value or larger accommodation for tourists. Figure 4 (page 10) shows Airbnb listings compared to the number of hotel rooms across all boroughs. The most popular leisure and tourist have the highest number of both Airbnb listings and hotel rooms. Boroughs located near airports showed hotels as the dominant accommodation option, this could be attributed to a lack of residential space in these areas.

PWC (2016) concluded that there will be increased usage of shared platforms across different age cohorts for business and leisure travellers. Within the London region, the current trend of increased Airbnb listings is likely to continue, causing pricing pressure and/or underutilisation within the hotel sector, especially for undifferentiated products.

Figure 6 Hotel Rooms and Airbnb Listings by Borough (Source: PWC, 2015)

Â

Peer-to-peer platforms have emerged in recent years and, whilst economic benefits drive them, they have brought disruptive innovation to the accommodation sector of the hospitality industry. These innovations have enabled users to share underutilised assets like vacant rooms in their own residencies or second homes. This report has shown that Airbnb compete with traditional hotels on price, in particular two and three-star hotels in the leisure market, in addition, they also offer benefits to guests looking for experiential value like contact with locals, being part of a community and staying in residential areas. However, the appeal of peer-to-peer sharing platforms like Airbnb will always have limited appeal as some tourists will opt for the more predictable experience of staying in traditional a traditional hotel. According to Mayock (2013) “peer-to-peer booking sites attract a certain type of traveller – typically those who are a bit more adventurous and don’t demand certain standards and amenities”. Michelle Grant, Travel and Tourism Manager at the market research firm Euromonitor International, predicted that Airbnb will create greater competition for leisure travellers, however, hotels can respond by promoting their extended stay brands and emphasising the family friendliness of their properties. Business travellers will remain loyal to hotels due to their corporate travel policies, loyalty programmes, and standardised service (Grant, 2013).

Secondly, potential threats may be dismissed in that peer-to-peer accommodation sharing models exist in parallel with, rather than in competition with, traditional hotel accommodation. It is worth nothing that, Airbnb claim that its market offerings compliment the hotels offerings by attracting a different type of tourist, thereby making the pie bigger, rather than taking a slice of the pie. Grant (2013) places Airbnb within the vacation rental market, therefore they are not able to cannibalise the hotel market. She says, ‘Both business models have co-existed for a significant amount of time without infringing on each other’s growth’.

The hotel industry can respond by adopting some of the experiential elements Airbnb offer:

- Offer more customised and personalised services. This requires hotels to move away from standard operating procedures and to focus on personal attention and guest experience.

- Change their current offer to include more budget hotels that include unusual design features and high-quality food and beverages. This could include the use of repurposed buildings where the original function of which becomes part the guest experience.

- Look at building links between guests and locals through social innovation projects like food and beverage outlets.

Â

Table 1Airbnb Rates in Comparison to Hotel and Hostel Rates (Guttentag, 2013)

Christensen, C. (1997). Innovators dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Â