Diversity in Gender and Governance

Â

INTRODUCTION

In the past, women could only be at home and do the household chores while the majority of men went to work. They did not have the rights to work. However, this orthodox view has been changed. In today’s society, more and more women are going to work than ever before. The figures from Statistics Canada (2017) show that more than 9 million women in Canada have jobs at the end of 2016. As it can be seen, the number of females in the labor force increased substantially. Not only do women work as employees but they are also employers as well. They hold many important positions in companies such as chiefs, managers, members or the chairman of boards. In Canada, women hold 21.6% of board seats in the Financial Post 500 in 2016 (Catalyst, 2017). According to Catalyst’s research, it shows that the percentage of women directors in many developed countries has been increasing significantly. For example, in Australia, it represents 23.4% of women on boards in June 2016, which almost tripled than that of 2009. Growth in the number of women allows companies to grow faster and become more successful. As a business student, we are interested in the contributions of women to the economy. They play an important role in developing the firm values. Dr. Mijntje Lu¨ckerath-Rovers (2011) has investigated that enterprises with female managers run better than those with men only. Moreover, women can bring their unique skills, which male counterparts cannot, to diversify a wide range of the board’s expertise (Kim and Starks, 2016, p. 270). They suggest that diversity in gender enhance higher firm values. Even though society makes an endeavor to fight for gender equality, there is no sign that this controversial issue will disappear. In this paper, we provide more in-depth evidence that the presence of women on boards develops companies’ performance actively and effectively based on personal research and surveys. We will also answer one of the fundamental questions: “Will gender diversity be encouraged in the future? How would it change: in a good way or bad way?”

DEFINITION

The Dictionary of Business in 1996 (as cited in Walt and Ingley, 2003, p. 219) indicates that diversity in boards is a mix of human capital, where human capital is represented as the skills and knowledge absorbed by a person through the process of learning and experience. In the context of governance, diversity is described as “the composition of the board and the combination of the different qualities, characteristics and expertise of the individual members in relation to decision-making and other processes within the board” (Lückerath-Rovers, 2011, p. 493). Therefore, one of the aspects of diversity is gender on boards. This paper only focuses on gender diversity for several factors. First, gender diversity is one of the major topics which has been fiercely debated for a long time. Secondly, “gender is the most easy distinguished demographic characteristic compared with age, nationality, education or cultural background” (Lückerath-Rovers, 2011, p. 493). Eventually, our research aims to show that diversity in gender makes all the difference in firm performance.

BACKGROUND

According to a 2017 statistical analysis conducted by Statistics Canada, among women in the labour force, approximately 94% of them are employed (full-time and part-time). This proves that the labour force changed rapidly and there are more rights for women than ever before. European countries now appear to take the lead in the number of women directors (Catalyst, 2017). This survey also shows that many countries, such as Norway, Iceland, Finland and Sweden, are using quotas and setting targets to expanding the number of women on boards. However, in some Asian countries, there are only a tiny number of female directors. Catalyst’s research series, The Bottom Line, indicates that the more women on boards a company has, the better financial results they receive. For example, “Companies with the most women board directors had 16% higher Return on Sales (ROS) than those with the least, and 26% higher Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)” (Catalyst, 2017).

WOMEN’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO CORPORATE BOARDS

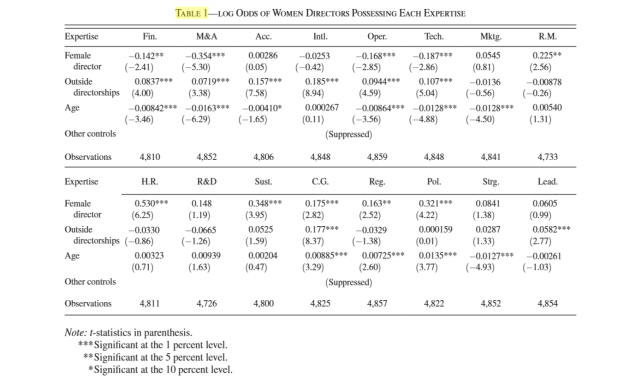

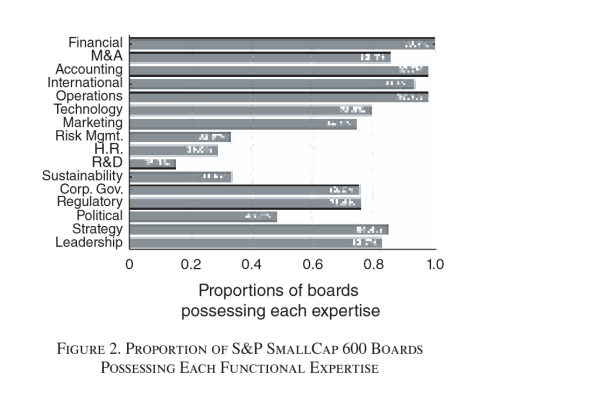

According to the research in 2013 on gender diversity in S&P 1500, which is a stock market index of US stocks made by Standard & Poor’s, about a quarter of its firms still have no female directors. With data from the ISS RiskMetrics and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, other smaller firms include S&P 600 SmallCap, S&P 400 MidCap, and S&P 500 indices, the proportion of women on their boards just makes up by a small percentage (only 37%, 21% and 7% respectively have no women on their boards). However, surveys report that women are rated higher than men on the emerging leadership qualities of many aspects. As reported by the 2009 SEC Final Rule No. 33-9089 Proxy Disclosure Enhancements, there are in total 16 functional types recommended as critical skills: Financial, Mergers and Acquisitions, Accounting, International, Operations Technology, Marketing, Risk Management, Human Resources, Research and Development, Sustainability, Corporate Governance, Regulatory/Legal/Compliance, Political/Government, Strategy and Leadership. Results show that adding women directors can enlarge diversity in corporate boards. Women are found to possess more uncommon expertise than men, which are four out of five least reported board skills (Research and Development, Human Resources, Risk Management, Sustainability, and Political Government). This shows that female directors can contribute both unique skills and expertise that are currently in distinction in the corporate boards, which can develop the heterogeneity of board skills. As a result, women directors can increase the value in corporate boards and enhance boards’ advisory effectiveness by adding these skills. Gender diversity is therefore related to higher firm value, and better director heterogeneity of expertise can increase the development in corporate boards.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN MEN AND WOMEN AS DIRECTORS

Although some studies have found that men and women as directors and leaders do not differ in the way of thinking, orienting tasks and other people, women actually learn how to be a leader more easily than men. The reason for which is that girls are likely to be raised with a more egalitarian way than boys, this could affect the way they participate in their life. Also, as stated above, women have more unique skills than men, which translates into their relatively greater use of participative leader style. Another reason could be that gender stereotypes have somewhat affect female leaders to be more competitive in firms. They would care more about follower expectations and be more interested in complying with it.

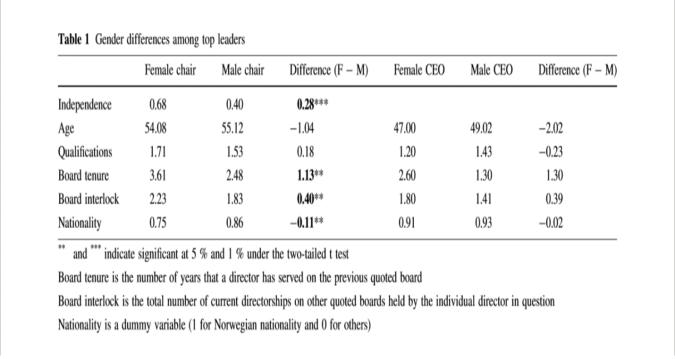

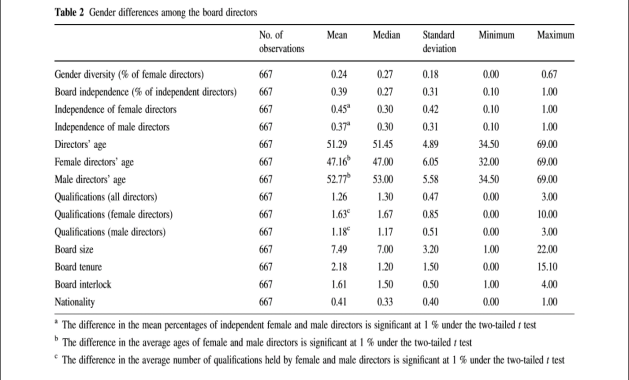

There are differences between men and women as both board directors and top leaders. As top leaders, men and women tend to have no difference in ages and qualifications. Nevertheless, female directors are more independent due to their better multi-directorships. According to research in Norway, 45% of female directors and 37% of male directors are outsiders. While female directors with an average age of 47.16 years and an average of 1.63 qualifications, male directors hold only average 52.7 years have 1.18 qualifications (Wang and Kelan, 2012, p. 456). The result shows that women are not only younger but also more educated than their male colleagues. It also reports that one female director in firm has 10 qualifications in average, while that number of other directors is just 3. Men as directors do not have as many resources through serving multiple boards as women, and are less likely to be outsiders than women. Female directors are reported to be younger and have more qualifications than male directors, while there is no significant difference between male and female as CEOs in some specific aspects such as age, qualifications and experience within the boardrooms and the corporations.

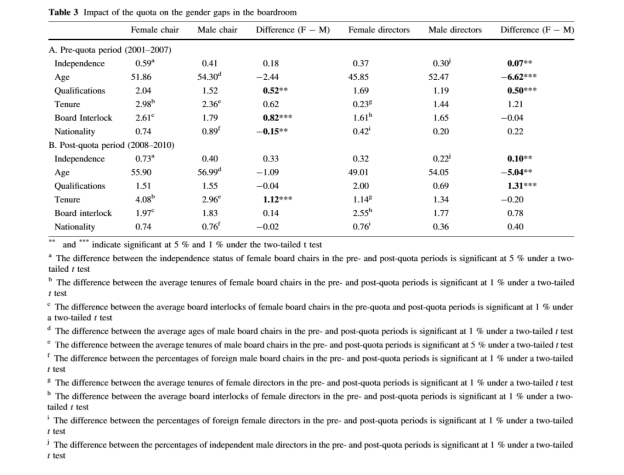

The gender gaps and the differences between female and male leaders and directors are also affected by gender quota. As stated in , gender quotas are used to create equal representation among gender within legislation contribute to the promotion of gender equality, and ease the access of women into positions of government. “Gender quotas were first introduced in some public sector entities in the 1980’s and were extended in 2003 under legislation requiring at least 40% of women on boards of public limited companies (known as ASA), inter-municipal and state-owned enterprises” (Sorsa, 2016). The enactment of the mandatory gender quota became one of the researchers’ studies since its introduction in Norway in 2005 (Wang and Kelan, 2012, p. 451). According to Ahern and Dittmar’s report in 2011, even though the increasing number of women was found to boost the board’s strategy and effectiveness, this has led to the surge in the number of inexperienced women in corporate boards, which could damage the firm’s performance. However, Matsa and Miller (2011) found that there are positive effects of gender quota on firms, especially on the reductions of workforce and the rise in relative labor costs, compared with a matched sample in Scandinavia countries without gender quotas. The outcome shows that the gender quota in Norway created only a few experienced women as top leaders on their boards based on a number of proxies for influence, such as leadership and multi directorships, though this country has been increasing a large number of women in their firms (Seierstad and Opsahl, 2011).

Despite the fact that there are no specific differences between the way women and men lead, gender diversity is still an important factor on boards and it may influence female directors’ contributions to board decision-making processes (Nielsenand and Huse, 2010). At the same time while having a female leader in the boardroom can make female directors easier to feel comfortable about expressing their opinions, male leaders show respect and openness towards views raised by women (Wang and Kelan, 2012, p. 451). They also report that “female leaders not only enhance the effectiveness of board decision making but also benefit the operation of the organization.” Female board chairs had more qualifications than their male counterparts during the pre-quota period, but this difference vanished after the gender quota had been enacted. This shows that “female and male board chairs have similar levels of interlocks and are equally like to be foreigners” (Wang and Kelan, 2012, p. 451) during the post-quota period. However, compared the pre- with the post-quota period, female board chairs seem to be more likely to have independent qualifications, more experience and less board interlocks, while male board chairs are older and more experienced after the full compliance of the gender quota in 2008. The average tenure of female board chairs in the pre-quota period, which is 2.04, is significantly lower than the one in the post-quota period (2.98), and female board chairs are more likely to be foreigners in both periods (Wang and Kelan, 2012, p. 451). This shows that Norwegian firms have talented female top leaders locally, not “importing” them from other countries.

Results shown in these tables indicate that female directors are likely to be more independent and younger and have more qualifications than their male counterparts. Differences in independence status, age and qualifications between men and women as directors did not change after the full compliance in Norway in 2008. Women in the post-quota period are more experienced, have more board interlocks and are more likely to be foreigners than those in the pre-quota period, while male directors seem to be more independent in the pre-quota period than in the post-quota period.

The differences between male and female directors also result from gender quota. After the legislation for gender quota in Norway was enacted in December 2005, the Norwegian seemed to be under the pressure of hiring more female directors and therefore it resulted in the large number of inexperienced and low-educated female directors in corporate boards. Figures in Table 2 indicate that the average number of female’s qualifications decreased than that of male directors. This means that the female directors in sample firms need to have a wider range of qualifications to achieve the fixed gender quota. The effects of gender quota on characteristics of directors in Norwegian firms have reflected that there was no difference between male and female directors, with respect to independence, age and qualification in 2001 and in 2010 (which was 5 years before and after the enforcement of gender quota). However, the differences in age and qualifications seemed to have widened over the period from 2003 to 2005, while that in independence seemed to be narrowed over the same period. Firms may have recruited younger but less independent female directors with more qualifications when they had the choice of voluntarily increasing the number of female directors on their boards. Therefore, age and qualifications somewhat have contributed to help corporate governance because the newly nominated female directors would have lacked the experience and independence to monitor firm management well (Wang and Kelan, 2012, p. 460).

CONCLUSION

With gender equality, having females on boards is an indisputable fact. The heterogeneity among companies is related to higher firm value. The profits women can make for companies are much higher than those without women on boards. We can see that the relationship between gender diversity and governance are likely to be positive. There are several journals, articles and research that show the contributions of women to developing firm value. However, diversity in gender on boards has both positive and negative effects on governance. “The question of the relationship between gender diverse boards and firm value has generated considerable debate as well as analyses with conflicting findings and conclusions” (Kim and Starks, 2016, p. 270). For example, the impact on decision-making and financial performance related to gender diversity is complex because there are other factors that affect the firm’s conduct. Moreover, getting companies to commit and change their perceptions would be no easy task. In many countries, their thoughts have not changed since feudalism. For instance, it is difficult to put up with the presence of female directors in Asian companies. They think that having women on boards can waste their money, which leads to a reduction of their productivity because of several reasons: maternity leave, lower retirement age, etc. From our study, we emphasize the mechanism through which director heterogeneity improves firm performance. More female directors on boards can make female employees dedicate themselves to work and improve the performance of the firms (Lückerath-Rovers, 2011, p. 507). She also proves that companies are more successful in making use of the whole talent pool for competent directors instead of only half of the talent pool. As a consequence, the increase or decrease in the firm value depends on companies’ choices.

REFERENCES

Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the Boardroom and Their Impact on Governance and Performance. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1107721

Ahern, K. R., & Dittmar, A. K. (2011). The Changing of the Boards: The Impact on Firm Valuation of Mandated Female Board Representation. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1364470

Catalyst (2017). Quick Take: Women on Corporate Boards Globally. Retrieved from

Kim, D., & Starks, L. T. (2016). Gender Diversity on Corporate Boards: Do Women Contribute Unique Skills? American Economic Review, 106(5), 267-271. doi:10.1257/aer.p20161032

Lückerath-Rovers, M. (2011). Women on boards and firm performance. Journal of Management & Governance, 17(2), 491-509. doi:10.1007/s10997-011-9186-1

Matsa, D. A., & Miller, A. R. (2011). A Female Style in Corporate Leadership? Evidence from Quotas. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1636047

Sorsa, P. (2016). Gender quotas for corporate boards – do they work? Lessons from Norway. Retrieved from

Statistics Canada (2017). Full-time and part-time employment by sex and age group. Retrieved from

Statistics Canada (2017). Labour force characteristics by sex and age group. Retrieved from

Walt, N., & Ingley, C. (2003). Board Dynamics and the Influence of Professional Background, Gender and Ethnic Diversity of Directors. Corporate Governance, 11(3), 218-234. doi:10.1111/1467-8683.00320

Wang, M., & Kelan, E. (2012). The Gender Quota and Female Leadership: Effects of the Norwegian Gender Quota on Board Chairs and CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(3), 449-466. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1546-5

Wikigender. (n.d.). Debate on Gender Quotas. Retrieved from