Effect of Health Conditions on Labour Market Status

Introduction

The growth and development of every nation, region, metropolitan area and county depends on the quality of human resources. Tallman and Wang (1994) and Lin (2003) were of the view that quality human resources contribute to long-term economic growth. Forbes, Barker & Turner (2010) defined human capital as a set of attributes possessed by an individual that makes him or her able to contribute to production. Therefore, an individual with good quality human resources is a person rich in accumulation of knowledge and who possesses skills that lead to increased productivity and performance in the labor market (Lin, 2003).

Many young adults enter the labor market with the expectation working until retirement. But, most of them either leave or die before retirement because of health conditions especially those with some chronic diseases. These health conditions reduce their productivity at work and the number of hours worked.

Research conducted by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) indicated that chronic diseases[1] represented seven of the top ten causes of death in the United States in 2010. The chronic diseases accounted for 65.8% of all deaths among males and 67.2% of all deaths among females in United States in 2010. In addition to the pain and death that chronic diseases accounted, it diminishes both physical and mental capabilities that sometimes leads to disruption normal work (Chirikos 1993).

Chronic diseases[2] and related risk factors may affect labor productivity and labor supply, which have adverse effects on individuals and households. Therefore, health affects a worker’s wage through productivity. Workers with chronic diseases and other related risk factors can work for fewer hours. The theoretical underpinning of this effect is that healthier individuals are more likely to produce more output per hour worked considering that healthy people have better physical and mental capacities (Suhrcke, Nugent, Stuckler and Rocco, 2006).

Counterintuitively, economic theory suggests two effects of health on labor productivity and labor supply. The two effects are substitution and income effect. According to Borjas, substitution effect implies that an increase in the wage rate increases hours worked when real income is held constant (Borjas, 2016:39). Applying this to the study, if the outcome of poor health is to reduce wages through lower productivity, this would increase leisure and therefore lower labor supply since worker compensation from work is likely to diminish (Suhrcke et al., 2006; Currie and Madrian, 1999). For the income effect, increase in wage gives the worker a variety of consumption choices that increases her demand for leisure and decreases labor supply (Borjas, 2016:39). To avoid a reduction in wage rate that can affect lifetime earnings due to lower productivity, the worker has to increase the number of hours worked with the chronic condition (Borjas, 2016; Currie and Madrian, 1999). This could further worsen the health of the worker, because the worker does not want to remain unemployed.

Motivation

Policy-makers and legislators have been targeting health at both macro and micro levels to construct policies aimed at economic prosperity and improving the well-being of citizens. Some employers discriminate against individuals who have some chronic diseases because they think that these individuals are not productive and can only work for fewer hours. This imposes a burden to government by setting aside a fund in to support individuals who cannot work because of their health.

Health is seen as a determinant and a contributor to labor outcome decisions. Chaudhry, Faridi & Anjum (2010) identified two channels through which ill health reduces workers’ output productivity and labor supply. They argued that the two channels are absenteeism from work and presenteeism[3]. The effects of presenteeism on firms are likely to vary depending on the duration of the employee’s illness. If it is short-lived, companies may require remaining employees to work in that position. Sometimes, this becomes a burden to other employees because they have to work harder or stay for longer hours to meet the shortfall due to their colleague’s illness (Forbes, Barker & Turner, 2010).

When the sickness persist for long time, the firm would have to replace the sick worker. The reason being that, they want to avoid increase in operational costs which might lead to reduction in profit. Grossman viewed health as a capital stock that produces an output of healthy time. Thus, a worker allocates this healthy time between leisure and work. So, a worker with poor health has to allocate some of his or her time to treat himself or herself, which tends to reduce productivity (Grossman, 1972). The effect is that it reduces the income generating capacity of the organization as well as the wage of the worker. The wage received is based on the number of hours worked, so less time means less earnings.

Most previous studies measured health conditions from individual self-assessments about how well the worker feels. However, two individuals will not rate their state of health identically although they have identical illnesses. This leads to some biases of that this study will avoid by using the measured health. That is, whether a person has chronic disease or not.

In the light of this, other authors have written many papers on the relationship between health on labor market (Suhrcke et al., 2006; Currie and Madrian, 1999) for older workers and those at their retirement age. But, less or no work has been done on youth with chronic diseases. This study will contribute to existing literature by using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 to analyze the effect of health conditions on labor market status such as productivity (wages) and labor supply among young adults.

Research Questions

Typically, most studies have been done on older males and females while the extent to which health affects younger males and females in the workforce has been largely ignored. Therefore, the study will analyze the effects of health condition labor market status among young adults in United States.

To address the main question, specific questions will be answered. First, do human capital factors affect wages? How does chronic illness affect individual productivity through wages? What is the effect of health on labor supply? Furthermore, does socioeconomic factors affect wages?

The policy implication of this study would inform government how policies can be designed to improve the longevity of people with chronic diseases. This can be in a form of reduction prices on certain drugs. This will help the individual stay longer in the labor market if he or she can purchase drug at a reduced price. However, if there is no intervention, this affects the consumption and saving decisions of the individuals because they cannot accumulate much income for their retirement. The government can subsidize healthcare for the young adults with chronic diseases. Although, there are some social intervention programs in the health care for the older workers but there should be a special policy design for the young adults. A country with youthful population must design policies to protect the young adults especially those with some chronic diseases.

Research Hypothesis

Based on the research questions, the following hypothesis will be tested;

Based on the research questions, the following hypothesis will be tested;

: There is no significant relationship between human capital factors and wages.

: There is no significant relationship between human capital factors and wages.

: There is significant relationship between human capital factors and wages.

: There is significant relationship between human capital factors and wages.

: There is no significant relationship between chronic diseases and individual productivity through wages.

: There is no significant relationship between chronic diseases and individual productivity through wages.

: There is significant relationship between chronic diseases and individual productivity through wages.

: There is significant relationship between chronic diseases and individual productivity through wages.

: There is no significant relationship between health and labor supply

: There is no significant relationship between health and labor supply

: There is significant relationship between health and labor supply

: There is significant relationship between health and labor supply

: There is no significant relationship between human capital factors and labor supply

: There is no significant relationship between human capital factors and labor supply

: There is significant relationship between human capital factors and labor supply

: There is significant relationship between human capital factors and labor supply

Initial review of related literature

This section will review literature to the topic. This will include the empirical literature and theoretical literature related to the study. The literature review will serve as the basis for which the methodology of the study will be formulated and also provide the framework for the analysis of results.

Empirical literature

Gambin (2005) used European Community Household Panel (ECHP) to investigate the relationship between wages and two measures of health: general self-assessed health[4]; and whether the respondent reported having any chronic physical or mental health problem, illness or disability. The results revealed that good health has a significant positive effect on wages throughout Europe. Moreover, self-assessed general health has more effect on men’s wages, but chronic illness has a greater effect on women’s wages. The difference between Gambin’s study and this study is that the effects of health on wage was based on employed young adults rather than the older adults. However, this studies looks at how health and education affects young adult’s productivity and labor supply by controlling for gender and other explanatory variables. Gambin’s study looked at the cross country analysis among fourteen European countries, but this study will look at young adults in 2013 cohorts in United States. This study will include Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) as a proxy for the ability to measure worker’s capabilities whereas Gambin’s study did not. Gambin’s study included self-assessed health status as one of the measure of health which has a problem of subjectivity[5] bias. To avoid such problem, this study will use self-reported as a measure for the health conditions; whether the individual has chronic disease or not. According to Currie & Madrian (1999), the main problem associated with the use of self-reported measures is that measurement error is unlikely to be random. For instance, individuals who have fewer worked hours or have exited the labor force are likely to attribute it to the fact that they have poor health status. Workers with less labor supply tend to benefit from government programs and often indicate that they are unhealthy (Currie & Madrin, 1999).

Morgan, David, Cohen & Brazer (1962) included a measure of health status in their earnings equation. Their results revealed that health status is important for labor outcomes such as labor force participation, hours worked per year and hourly wage. Their main findings were that health impacted labor force outcomes such as earnings and employment greatly. One of the drawbacks in their study was that the sample size was small for the generalization. Also, they included age and age squared as a proxy for experience and experience squared, respectively. Experience is the number of years since a person left full-time education. There might be some risk of misspecification when using age as a measure of experience. This is because a worker might be old enough but with fewer working years. However, Contoyannis & Rice (2000) argued that the use of age and age squared implied a significant concave and quadratic relationship with hourly wage and they are robust to other estimation techniques. To avoid this conflicting problem, this study will use number of weeks of total tenure at any job reported in the employer roster to measure experience. This gives details of the work experience gained by the worker and helps minimize the problem of misspecification.

Theoretical Literature

There are extensive theories concerning health and its impact on individual productivity and labor supply. This study will review theories like human capital model and health-capital model.

The human capital theory is considered as the traditional model. This model was developed by Mincer and modified by Becker to include functional forms. This functional form captures the effect of education and other variables on earnings for male and female workers separately (Becker, 1962; Mincer, 1974).

Health-capital theory also predicts a link between health and longevity, though in the other direction. According to Grossman there is a causal effect of education on health and longevity. He argued that the more educated a person is, the more efficient employers invest in the health of their employees to stay healthy (Grossman, 1972).

Purpose of study

This study will contribute to literature by examining the effects of health on labor market status such as individual productivity and labor supply among young adults in United States.

Methodology of the study

Data description and Sample

This study will use 2013 cohorts from the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), collected for a national sample of youth first interviewed in 1997 when aged 12-18 years and interviewed subsequently each year. This study will look at young adults in 2013 cohorts because it is the most recent data released when fielded in 2013-2014 but updated in 2015. In addition, the dataset released in 2013 was chosen because more youth were diagnosed of various chronic diseases such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, arthritis etc. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). The study will use data after the Great Recession in 2008 to determine whether and how this crisis altered the consequences of health on individual productivity and labor supply.

The total number of people sampled are 8984. Particularly, this data contains analysis of detailed information regarding the health, education attainment, hourly wages and duration of employment during the survey years, as well as oversamples of key groups of economic minorities.

Appendix 1 shows descriptive statistics and Appendix 2 contains variable definitions.

Model Specification

The study will adopt the modified functional form of human capital model hypothesized by Mincer (1974) by including health in order to establish statistical relationship between health and other variables on individual productivity[6] and labor supply[7].

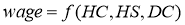

Theoretically,

——————————————– (1)

——————————————– (1)

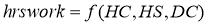

—————————————-(2)

—————————————-(2)

Where HC represents human capital factors like highest grade received, experience, ability. HS is the health status of a worker. This is whether the worker has a chronic disease or not, and DC represents the demographic factors such as gender, race and location (living in urban or rural). Education, experience and ability are the original values from the survey. However, the study will include the quadratic term in the experience variable to reflect if wage decreases as an employee gets to the peak of his or her career. Qualitative variables include health status, gender, race, and whether the individual lives in a rural or urban setting. The qualitative variables will assume the value of 1 if the statement is true or exist and 0 otherwise.

Estimation Technique

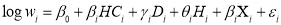

This section briefly describes the multivariate model that will be used to estimate the effects of education and health conditions on wages. The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression technique will be employed for the empirical analysis. The modified Mincer’s (1974) model will be used to estimate the effects of education and health on wages. Also, natural log of hourly wages[8] will be expressed as a linear function of years of schooling, chronic diseases, experience and other variables. Equation 1 can be expressed in empirical form in equation 2

—————————————- (3)

—————————————- (3)

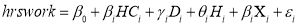

And that of labor supply is represented in equation 3

—————————————- (4)

—————————————- (4)

Where:

is dependent variable and represents the individual labor productivity.

is dependent variable and represents the individual labor productivity.

is the hours worked. This represents the dependent variable as a proxy for the labor supply

is the hours worked. This represents the dependent variable as a proxy for the labor supply

represents the human capital variables including education, ability, experience etc;

represents the human capital variables including education, ability, experience etc;

represents a vector of dummy variables;

represents a vector of dummy variables;

is a vector of dummy of health variable;

is a vector of dummy of health variable;

is a vector of control variables including demographic characteristics, occupations;

is a vector of control variables including demographic characteristics, occupations;

is the error term captures all other unobserved and observed factors that might affects this study but were not captured and it satisfies all OLS assumptions.

is the error term captures all other unobserved and observed factors that might affects this study but were not captured and it satisfies all OLS assumptions.

References

Borjas, G. J. (2015). Labor economics (7th ed). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). The state of aging and health in America 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Chaudhry, I. S., Faridi, M. Z., & Anjum, S. (2010). The effects of health and education on female earnings: Empirical evidence from district Vehari. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 30(1), 109-124.

Chirikos, T. N. (1993). The relationship between health and labor market status. Annual Review of Public Health, 14(1), 293-312.

Contoyannis, P., & Rice, N. (2001). The impact of health on wages: evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Empirical Economics, 26(4), 599-622.

Currie, J., & Madrian, B. C. (1999). Health, health insurance and the labor market. Handbook of labor economics, 3, 3309-3416.

Forbes, M., Barker, A., & Turner, S. (2010). The effects of education and health on wages and productivity. Productivity Commission.

Gambin, L. (2005). The Impact of Health on Wages in Europe – Does Gender Matter? University of York Health, Econometrics and Data Group Working Paper 05/03.

Grossman, M. (1972). The Demand for Health-A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation.

New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lin, T. C. (2003). Education, Technical Progress, and Economic Growth: the Case of Taiwan. Economics of Education Review, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 213-220.

Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, Experience and Earnings .New York: National Bureau of Economic.

Morgan, J. N., Martin, D. H., Cohen, W. J., & Brazer, H. E. (1962). Income and welfare in the United States.

Pedersen, K. M., & Skagen, K. (2014). The Economics of Presenteeism: A discrete choice & count model framework (No. 2014: 2). COHERE-Centre of Health Economics Research, University of Southern Denmark.

Rocco, L., Tanabe, K., Suhrcke, M., & Fumagalli, E. (2011). Chronic diseases and labor market outcomes in Egypt.

Suhrcke, M., Nugent, R. A., Stuckler, D., & Rocco, L. (2006). Chronic disease: an economic perspective.

Tallman, E. W. and P. Wang (1994). Human Capital and Endogenous Growth: Evidence from Taiwan. Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 101-124.

|

Variable |

No. of observations |

Mean |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

Gender |

8984 |

1.4880899 |

1.0000000 |

2.0000000 |

Appendix 1: Summary of descriptive statistics

Source: NLSY 97

Appendix 2: Variable definitions

|

Variable |

Definition |

|

Wages |

Dependent variable. Hourly wage |

|

Hours worked |

Dependent variable. Use as a proxy for labor supply |

|

Experience |

Number of years in current job. Weeks worked in employee job per 52 weeks |

|

Type of employment |

Full-time= Above 35 hours per week Part-time= below 35 hours per week |

|

Ability |

Maths/Verbal test and score based on percentiles |

|

Education |

Grade 12=high school Grade 14=college/bachelors Grade 16=Masters Above Grade 18=Ph.D Grade 0= no education |

|

Health |

= 1 if he or she has chronic diseases, = 0 otherwise |

|

Marital status |

= 1 if he or she is married, 0= otherwise |

|

Mother’s education |

= 1 if mother is educated, = 0 otherwise |

|

Father’s education |

= 1 if father is educated, = 0 otherwise |

|

Location |

= 1 if located in urban area, = 0 otherwise |

|

Occupation classification Managerial Professionals Technician Sales Administrative Service Farming Repairers laborers |

Based on 1990 Population Occupational Classification System legislators, senior officials and managers Professional technicians and associate professionals Sales support Clerical and administrative support service workers skilled agricultural, hunters and fishery workers mechanics, plant and system operators Laborers, transportation and material movers, helpers |

|

Family income |

Proxy for family Assets |

|

Sex |

= 1 if male, =0 if female |

|

Race |

= 1 if white =0 if black |

[1] Chronic diseases are an important public health problem, which can result in morbidity, mortality, disability, and decreased quality of life (CDC, 2013).

[2] Chronic diseases includes asthma, a cardiovascular or heart condition, anemia, diabetes, cancer, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, a sexually transmitted disease other than HIV/AIDS, or another chronic health condition or life-threatening disease according to National Longitudinal Survey

[3] Pedersen & Skagen (2014), presenteeism relates to a situation in which workers are on the job but, as a result of illness, injury, or other health related conditions, they are not functioning at maximum levels. For absenteeism, the worker will not be at work because of poor health conditions but for presenteeism, the worker would be at work despite some health problems.

[4] He used Likert scale questionnaire that ranges from excellent, very good, good, fair and poor.

[5] For instance, a person may be suffering from heart attack diseases or diabetes but because the worker is strong at that moment, the worker will report that he or she is strong.

[6] Hourly wage is used as a proxy for the individual productivity

[7] Hours of work is used as a proxy for labor supply

[8] This study will examine the effect of chronic conditions on hourly wage rates. In developed countries, wages are determined based on individual productivity. However, in developing countries, due to the rigidities in the labor market, wages are determined according to occupation and age rather than according to individual productivity (Rocco, Tanabe, Suhrcke & Fumagalli, 2011).