Effects of Derivatives

Banks and other financial institutions have progressively understood the need to measure and manage the credit risk they are exposed to. Derivatives, therefore have ascended in retort to the surge in demand of financial institutions to create vehicle tools for hedging and shifting credit risks. Derivatives over the years have become a valuable financial tools with system-wide benefits. However as innovative as the derivatives have been, they carry inside themselves so many threats that in the hand of inexperienced market participants, destabilize the whole economic system. Inside such a Pandora box were the instruments that would participate in amplifying the 2008 financial crisis. This paper postulates that derivatives may have contributed to the 2008 crisis.

Derivative contracts are probabilistic bets on future events, as defined on Investopedia they are securities with a price that are dependent upon or derived from one or more underlying assets. Many people argue that derivatives reduce systemic problems, in that participants who cannot bear certain risks are able to transfer them to stronger hands. These people believe that derivatives act to stabilize the economy, facilitate trade, and eliminate bumps for individual participants (Buffett, 2016). We have now reached the stage where those who work in finance, and many who work outside finance, need to understand how derivatives work, how they are used, and how they are priced (Hull, 2015). For this reason, derivatives are at the center of everything.

However, in 2008 the world witnessed a financial and economic hurricane that left massive financial and economic damages. It was universally recognized as the worst economic crash since the Great Depression. The old saying has it that success has a hundred fathers, but failure is an orphan (Davies, 2016). In this situation, it was the opposite as this failure had a long list of guilty men. While some argued that the changes in the law are the cause of the crisis, others pointed out the role derivatives played via the crash in the value of subprime mortgage-backed securities.

The main thesis of this paper is that, while derivatives contributed a lot for the financial market would we be better off them? After a discussion of the positive effects of derivatives (their ability in refining the management of risk), the paper will analyze the negative aspects of them (enhancing risk-taking, evading taxes and creating financial crises). And we finish by looking at how derivatives fueled the financial crisis.

Derivatives are instruments that derive their performance from some other instruments or assets. In contrary to the spot market, derivative markets require less capital and usually are more liquid. Higher liquidity means more efficiency such that prices change more rapidly in response to new information, which is a good thing (Chance, 2008). There are different types of derivatives that an individual can use to protect himself against volatile time. Derivatives confer to the financial market different types of benefits such as risk management, price discovery, enhancement of liquidity. Fundamentally they are instruments that permit the transfer of risk from a seller to a buyer. Exporters, exposed to foreign exchange risk, can reduce their risk using derivatives (forward, futures, and options) (Viral & Richardson, 2009). Derivatives can be viewed as insurance; one party gives up something in order for the other party to accept the risk. Some say that derivatives are nothing more than gambling (Peery, 2012). But derivatives can be compared more to insurance than be called gambling. In insurance, we have an insurer collecting the premiums where in derivatives, we have speculators receiving fees for speculation. Without speculators, hedging risk is impossible.

Another benefit is price discovery; derivatives provide information to the market about the expectations of people on the future spot price. The ABX indices (i.e., a portfolio of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) of subprime mortgages) which were one of the first instruments to provide information to the marketplace on the deteriorating “subprime” securitization market (Viral & Richardson, 2009). Moreover, they also give the opportunity to market participants to extract forward information instead of historical information. Such information is used, among others, by central banks in making policy decisions, investors for risk and return decisions on their portfolios and corporations for managing financial risk (Viral & Richardson, 2009).

An additional positive benefit is the enhancement of liquidity. When derivatives are added to an underlying market, it brings additional players who use the derivatives and give the opportunity to companies to earn income that would not be available to them or available but the cost would be high. By and large, spot markets with derivatives have more liquidity and thus lower transaction costs than markets without derivatives (Viral & Richardson, 2009).

If derivatives provide to the financial market all those useful benefits, how come they were accused of player a role in the financial crisis of 2008?

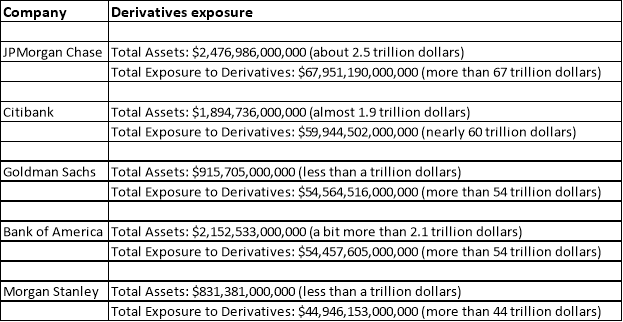

Derivatives play an important role in reducing the risk that companies face, but they are a synonym of danger to the stability of the financial market and in doing so, the economy in general. Within the field of finance, derivatives are the most dynamic instruments because they have no limits unless parties, markets, or governments set them (Peery, 2012). In his annual letter to shareholders in 2002, Warren Buffett branded derivatives as time bombs, both for the parties that deal in them and the economic system (Buffett, 2016). However, that fear of derivatives existed way before Warren Buffett expressed it. Max Weber’s 1896 essay on the stock exchange lingered over the concern that derivative contracts encouraged speculation and increased market instability (Maurer, 2002). Years after the financial crisis, (Hoefle, 2010) argued that derivatives were doomed from the start, that they were the answer to the stock market crash of 1987, the demise of the S&L industry, and bankruptcy of U.S banking system. Why are some people against the use of derivatives? At first, derivatives were tools that can be used to hedge against pre-existing risks, in another word a form of insurance. But as time went on, people realised that they can use derivatives in another form than insurance. They went from hedge to speculation, implying that they tried to earn a profit by prophesying future events better than another can, including future asset prices, interest rates, or credit ratings. While doing that most companies got themselves hugely exposed to derivatives. As you can see in the example I have in the appendix Table 1, most of those companies’ total assets cannot match the leverage the companies are facing throughout the use of derivatives. And when the corporation’s exposure becomes large to the overall market, that could translate to problems, for example the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. The company at that time had capital of $4 billion, assets of $124 billion, but their exposure to derivatives was more than $1 trillion. How all of these translated into becoming one of the causes of the financial crisis?

The Bank for International Settlements has only published statistics on the Credit Derivatives market since the end of 2004 when the total notional amount was $6 trillion (Stulz R. M., 2009). The market grew hugely and by the time we get to the middle of 2008 the notional amour was $57 trillion. Quickly Credit Derivatives became an important tool to manage credit exposure. There are different reasons to why market participants have found credit derivatives appealing. First you do not need a deep pocket in order to take a position, secondly, CDs can be used as insurance against any type of loans, not just a specific. In addition to that, the largest derivatives market is for swaps. With a swap, two parties exchange the rights to cash flows from different assets (Stulz R. M., 2009). In principle, credit default swaps should make financial markets more efficient and improve the allocation of capital (Stulz R. M., 2009). As time went on people were more focused on CD contracts on subprime mortgages. Although subprime mortgages carried inside them significant default risk, as other mortgages they were securitized. As (Stulz R. M., 2010) explained in his article, mortgages are placed in a pool, and notes are issued against that pool. In the pool, the highest notes always have an AAA rating. In the case of mortgages default, the lower-rated notes suffer first, but as the default losses increase the higher rated notes will be affected too. In 2006 the ABX indexes were introduced, it was based on the average of credit default swaps for identical superiority securitization notes. Every six months, ABX indexes played an important role as they made it possible for an investor to take positions on the subprime market, even though they have no ownership of subprime mortgages or as insurance for subprime exposure. As a result, it was possible for investors to bear more subprime risk than the risk in outstanding mortgages (Stulz R. M., 2009). As all good thing must come to an end, in 2008 financial institutions faced counterparty risks in derivatives that they had never factored in their calculations. René M. Stulz (2010) offers a more detailed explanation of the counterparty risks and the problem that can arise. As for the causes of the counterparty risk, some people argued that derivatives lead to huge web exposure across financial institutions. In case one of the financial institution fails, the others will follow. And as we saw with the failure of Lehman, which had at that time derivatives contracts with other financial firms. Those firms were expecting payments from Lehman on their derivatives. Sadly, for them, Lehman at that time had filed for bankruptcy. While they could have managed their exposure to the counterparty risk, as they were high rated counterparties something unexpected happened. The failure of Lehman had as consequence a huge increase in the price of derivatives, at that moment the collateral amount would not be enough to cover the default of other counterparties default. As a domino effect, most firms were hit by the default of Lehman and without the help of the government to bail them out some would not have survived. The CDs market grew too fast for its own good and it created a bubble that fooled the financial markets. The lack of regulations, transparency, and clarity in financial statements made it hard to prevent. And before people realised we were in what some people call the worse financial crisis of all time.

No matter the instruments you give to someone the results will depend on his intention. A good instrument in the hand of an evil person who focuses on profit over ethics will make that instrument look evil. Pablo Triana in his book “The number that killed us” gave a perfect example of a situation where a red Ferrari was involved in an accident that had civil casualties. Should we blame the car for the accident or the driver who was guilty of speed driving in the past? Same dilemma with the derivatives, we have seen how derivatives allow firms and individuals to take risk efficiently and to hedge risks. However, they can also create risk when they are not used properly. And the downfall of a large derivatives user or dealer may create a systemic risk for the whole economy. Which is why as for any instruments that may harm the world, derivatives should be regulated more effectively. We did not ban the atomic bomb after Hiroshima, nor we did with planes for their risk of a crash, but better regulations were introduced to make them safe as sense to be. While derivatives have been blamed, sometimes wrongly, for large losses – from Barings to Enron – the benefits are widely dispersed and may not make for good headlines. On balance, the benefits outweigh the threats (Balls, 2016).

Appendix

References

Ahmad, I. M. (2010). Greed, financial innovation or laxity of regulation? a close look into the 2007-2009 financial crisis and stock market volatility. Studies in Economics and Finance, 110-134.

Alnassar, W. I., Al-shakrchy, E., & Almsafir, M. K. (2014). Credit Derivatives: Did They Exacerbate the 2007 Global Financial Crisis? AIG: Case Study. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1026-1034.

Balls, A. (2016, 12 12). The Economics of Derivatives. Retrieved from nber.org: http://www.nber.org/digest/jan05/w10674.html

Buffett, W. E. (2016, 11 28). Letters. Retrieved from berkshirehathaway: http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2002pdf.pdf

Chance, D. M. (2008). Essays in Derivatives . New Jersey: Jonh Wileys & Sons.

Crotty, J. (2009). Structural causes of the global financial crisis: a critical assessment of the new financial architecture. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 563-580.

Davies, H. (2016, 11 20). The Financial Crisis: Who is to Blame? Retrieved from Google Books: https://books.google.ie/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MNH6q2YGEUkC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=financial+derivatives+and+crisis&ots=2_ZzDDFPS3&sig=JW59MDMZt2HWvDWthLHWtyDyZwc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=financial%20derivatives%20and%20crisis&f=false

Hoefle, J. (2010). Ban, Don’t “Regulate”, Derivatives. Executive Intelligence Review, 32-34.

Hull, J. C. (2015). Options, Futures, and other Derivatives. New York: Pearson Education.

Lebron, M. W. (2016, 12 20). Derivatives: The toxic financial instrument on par with terrorism . Retrieved from rt.com: https://www.rt.com/op-edge/325982-derivatives-toxic-instrument-review/

MacKenzie, D., & Millo, Y. (2016, 11 12). Negotiating a Market, Performing Theory: The historical sociology of a financial derivatives exchange. Retrieved from SSRN Electronic Journal : https://ssrn.com/abstract=279029

Maurer, B. (2002). Repressed futures: financial derivatives’ theological unconscious. Economy and Society, 15-36.

Peery, G. F. (2012). The Post-Reform Guide to Derivatives and Futures. New Jersey: John Wisley & Sons.

Stout, L. A. (2011). Derivatives and the legal origin of the 2008 credit crisis. Harvard Business Law Review, 1-38.

Stulz, R. M. (2009). Financial Derivatives: lessons from the subprime crisis. The Milken Institute Review, 58-70.

Stulz, R. M. (2010). Credit Default Swaps and the Credit Crisis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 73-92.

Triana, P. (2012). The Number That Killed Us: A Story of Modern Banking, Flawed Mathematics, and a Big Financial Crisis. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Viral , A. V., & Richardson, M. (2009). Restoring Financial Stability: How to Repair a Failed System. John Wiley & Sons.