Evaluation of UK Legislation and Policy on Fracking

|

AN EVALUATION OF CURRENT UK PLANNING LEGISLATION AND POLICY MEASURES TO CONTROL THE POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF FRACKING ON WILDLIFE CONSERVATION |

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Introduction

The pace of the development of Britain’s Shale-gas industry is accelerating due to the current government’s policy to progress the extraction of shale-gas, or ‘fracking’ as commonly known, to “provide energy security, growth and jobs” (DBEI. 2017). Commercial extraction of shale-gas is not yet in production, but exploration of the recoverable amount available is occurring. Shale-gas could potentially be a resource that transforms the UK energy market and contribute to the national security of supply. However, whilst the economic potential is apparent, the environmental and social implications are unknown. There have been reports of earthquakes (in Lancashire) (DECC 2013), leakage of fracking chemicals and gas (methane) into the water table, where fracking has occurred, most typically in the United States of America (Finkel and Hays 2016). There has also been campaigning by community groups opposed to fracking because of the environmental concerns. “Hydraulic fracturing involves injecting a viscous fracturing fluid carrying a proppant, usually select sand, which is left in fractures to hold them open and promote substance migration to wellbores” but advances in directional drilling with a greater horizontal reach means that multiple wells can be drilled from a single pad. (Zillman et al. 2015). However, this could include horizontal drilling beneath Nature Reserves, Country Parks, Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) etc. Some of the concerns by these new technologies are:

(a) Air emissions.

(b) Water quality and quantity (aquifer and surface water contamination by fracturing fluid chemicals).

(c) Potential seismic activity, particularly in major fault areas.

(d) Public participation in regulatory decisions concerning fracturing activities.

(e) Transparency, including public disclosure of chemicals and toxicity information.

(f) Disturbance creating dust, noise, and congestion in communities that host fracturing

operations. (Zillman et al. 2014.)

All of which have potential to impact upon humans and wildlife conservation.

Consequently, the Law and Policy surrounding fracking and the environment to conserve wildlife will be evaluated.

- Aims and Objectives

This study aims to evaluate current UK planning legislation and policy with regard to the potential impacts of fracking on wildlife conservation. An analysis of the controls available for the protection of wildlife and the compensation procedures that are currently in place will be discussed within this report. The analyses of concerns and opinions of the businesses involved, government policy, wildlife organisations, public and media opinions which may have an impact on future planning policies and procedures, habitat degradation, human health, and wildlife conservation will be undertaken. Case studies, government articles, fracking company media statement and media reports used to illustrate current approach. An analysis and evaluation comparison of two shale gas companies within the two counties of Nottinghamshire and Lancashire, both of which have had planning permission granted for fracking exploration sites. In the county of Lancashire, planning permission was refused not only for an exploration site but for extraction of shales gas. The company turned to the government to appeal this decision which was overturned. Preston New Road Action Group (a group of local residents) has subsequently appealed and the hearing is set for 15 March 2017. Therefore, are the strategies that are currently in place sufficient to meet all needs from both companies, the conservationists, the public and the government? To investigate and evaluate the policies and procedures required by the Shale gas companies to obtain planning permission to include Environmental Impact Assessments, are these effective, detailed sufficiently and acceptable? What are the procedures post damage or accident? Is this acceptable? Critical analyse of each perspective.

Methods & Materials

This evaluation analysis is a desktop review and will therefore not require the participation of human, animal, and environmental subjects. Information will be sourced from scientific and law books, scientific journals, media reports and websites (such as governmental, legal and the company’s websites). European Law will not be taken into consideration due to the imminent exit from the European Union. Therefore, only the Laws and policies currently in place for England and Wales are to be included. Some of the topics covered in this study will be: – Environmental Law; Law Commission Report 2012; National Planning Policy Framework; Environmental Impact Assessments of the sites in the two Counties; Company information of the two companies involved Caudrilla Resources and IGas plc. The criteria used when searching for information was based upon: Environmental Law; Fracking in the UK; Legislation and policy with regard to planning in the UK; Fracking in Lancashire; Fracking in Nottinghamshire; Hydraulic Fracturing; Shale Gas; UK Shale Gas & Fracking – House of Commons 2017; …….. to be completed. Not quite sure how to finish this off??

Chapter 2: Shale-gas Fracking

2.1 Overview of fracking.

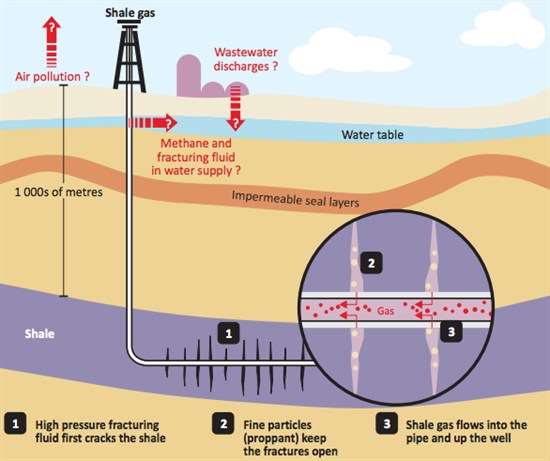

Extraction of a natural gas known as shale gas is found in shale rock formations that can be extracted by Hydraulic fracturing (fracking). The gas is mined by drilling a well down vertically until it hits the shale, then horizontally. This involves inserting high volumes of water mixed with chemicals into the rock to cause it to fracture and release the gas. See Figure 1. Currently the UK government supports fracking although concerns remain about the adequacy of current UK regulation of groundwater and surface water contamination and the assessment of the environmental impact.

Figure 1. Hydraulic Fracturing and environmental concerns (Carbon Brief 2013).

2.2 Legislation and policy relevant to fracking, and wildlife conservation.

Environmental regulation is intended to protect the environment. The impact and effectiveness of the legislation can be considered from several perspectives which seem to be fragmented and haphazard at best. Some of the law statutes for environmental protection include: –

- Clean Air Act 1956

- Clean Neighbourhood and Environmental Act 2005

- Control of Pollution Act 1974 as amended in 1989

- Environment Act 1995

- Environmental Protection Act 1990

- Freedom of Information Act 2000

- Law of Property Act 1925

- National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949

- Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006

- Nature Conservancy Council Act 1973

- Pollution Prevention and Control Act 1999

- Town & Country Planning Act 1990

- Water Resources Act 1991

- Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981

- Case Law will also be included where relevant.

The principles under common law governing property rights to the subsurface and to minerals are necessary to understand the law governing activities using geological developments. The general rule (with some exceptions) is that the rights deriving from the possession or ownership of an estate in land extends upwards and downwards. “The Latin phrase that expresses this rule is cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et ad inferos; to whom the soil belongs, to that person it belongs all the way to the sky and the depths” (Zillman et al. 2014). Therefore, permission from the land owner must be sort to enable permission for fracking to take place on privately owned land. In the case of Bocardo v Star Energy UK Onshore Ltd in 2010 the land owner sued the oil company for trespass for three wells made under its land for directional drilling. In the case Star Energy Weald Basin Limited (and another) v Bocardo SA (Supreme Court Judgment, 28 July 2010). There is no depth limit after which geological formations are owned by the state and that any invasion of it must have a physical effect on the surface. It could be said therefore that considering the risks associated with fracking and public opinion generally against fracking, land owners would not allow fracking upon their land but government incentives and fracking companies payments to allow access can be a high incentive to land owners. This could influence the conservation of wildlife if directional drilling undermines a special conservation site alongside a landowner that has agreed permission.

Who owns shale gas? Shale gas counts as “petroleum” within the meaning of the Petroleum Act 1998 and the rights are vested in Her Majesty. By section 2(1) of that Act. The Crown has the exclusive right of searching for and getting petroleum in its natural condition within Great Britain. The Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) issues licenses to companies for exploration and for mining. The Oil and Gas Authority (a department within the government) is responsible for awarding onshore oil and gas licenses, which include exploratory fracking operations. On 17 December 2015, the Oil & Gas Authority (OGA) announced that licences for a total of 159 blocks were formally offered to successful applicants under the 14th Onshore Oil and Gas Licensing Round (OGA 2017).

Proposals for shale gas exploration or extraction in England & Wales are subject to the requirements of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 administered by the Minerals Planning Authority (MPA) for the area in which the development is located. Individual town and city planners face a difficult task, they are required to consider the future economic and social needs of the community and provide the best possible environment in which to live and work (Evans, Stephenson, and Shaw 2009). Public and conservation charities opinion and opposition to the proximity of the well sites. The legal framework for land use planning and relevant legislation will be discussed individually for Lancashire and Nottinghamshire later.

In May 2015, the government issued a statement regarding sustainable development “making decisions now to realise our vision of stimulating economic growth and tackling the deficit, maximising wellbeing and protecting the environment, without affecting the ability of future generations to do the same” (DEFRA 2015). Each department within the government is responsible for their own policies and activities to create sustainable development with DEFRA overseeing decisions. As you will see from the statement: development, economic growth and tackling the deficit, comes as a priority before wellbeing and protecting the environment.

In June 2012, the government commissioned The Royal Society to compile a Review of Hydraulic Fracturing and their initial findings concluded… “The health, safety and environmental risks associated with hydraulic fracturing (often termed ‘fracking’) as a means to extract shale gas can be managed effectively in the UK as long as operational best practices are implemented and enforced through regulation” (RS and RAE 2012). However, they also made ten recommendations summarised as: to detect groundwater contamination, to ensure well integrity, to mitigate induced seismicity, to detect potential leakages of gas, water usage and wastewater should be managed in an integrated way, an Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) should be mandatory for all shale gas operations, best practice for risk management should be implemented. (RS and RAE 2012). These recommendations should be included within the planning and licensing applications.

On the 6 April 2016, section 50 of the Infrastructure Act 2015 came into effect introducing amendments to the Petroleum Act 1998 regarding when and how consent can be issued for hydraulic fracturing in relation to the exploration and production of shale gas. The changes to the Infrastructure Act 2015 gives the shale gas companies in England & Wales the means to access “deep level land” at least 300 metres underground for deep geothermal energy, one of which is shale gas. It also imposes a formal consent from the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change. It also originally stated that there would be a ban on fracking in National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) but SSSI’s have been excluded and now allow for underground fracking.

It should be noted that some regulators whom approve licenses for fracking, such as the Environment Agency, view prosecution as a last resort and prefer to adopt a ‘compliance’ strategy. The Environment Agency is a government run organisation who “work to create better places for people and wildlife, and support sustainable development.” (Environment Agency 2017).

Environmental permitting regulations cover:

- protecting water resources, including groundwater (aquifers), assessing and approving the use of chemicals which form part of the hydraulic fracturing fluid

- appropriate treatment and disposal of mining waste produced during the borehole drilling and hydraulic fracturing process

- suitable treatment and management of any naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM)

- disposal of waste gases through flaring

In the planning process the Environment Agency can be a statutory consultee and provides local planning authorities (county or unitary local authority) with advice on the potential risks to the environment from individual gas exploration and extraction sites (DBEIS 2017).

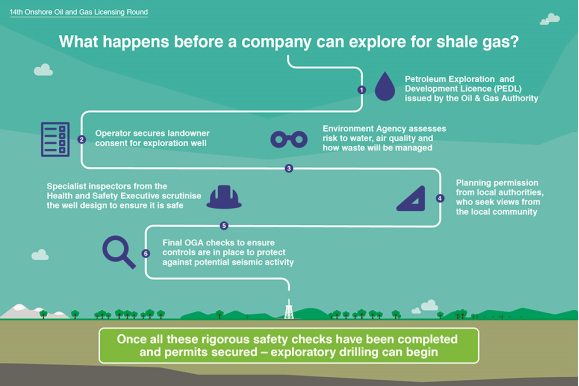

The government publish documentation to convince the public of the strict processes companies have to adhere to before obtaining approval, “operators pass rigorous health and safety, environmental and planning permission processes before any shale operation can begin in the UK” (DBEIS 2017). See figure 2.

Figure 2. Infographic: What happens before a company can explore for shale gas? (DBEIS 2017)

2.2 Impact on Wildlife Conservation, the concerns and public opinion.

The first resource for environmental implication impact to consider is water. The quality, quantity used, accessibility of the resource and waste water disposal.

Vast quantities of water mixed with proppant and chemical additives, for example: gelling and foaming agents, friction reducers, crosslinkers, breakers, pH adjusters, biocides, corrosion inhibitors, scale inhibitors, and surfactants are injected under pressure to release the shale gas and enable the gas to return to the surface. One third of them lack mammalian toxicity data (Stringfellow et al., 2014). The Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) 2013, states that it is likely to involve the use of large quantities of clean water, typically 10,000 to 30,000 m3 water per well (10,000 to 30,000 tonnes). The water may be obtained from the local water supply company sources or by abstraction from surface or groundwater (if permitted by the relevant environment agency under licence).

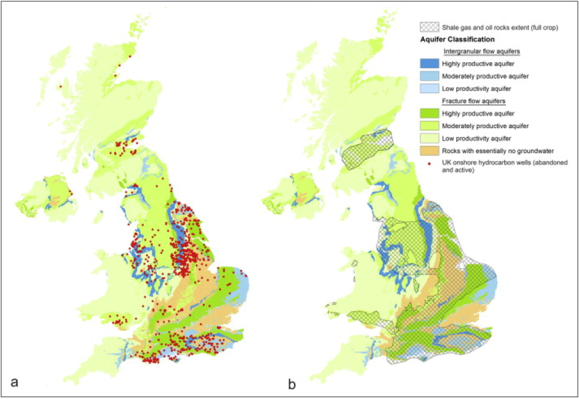

Loss of well integrity has led to contamination of surrounding strata by fracking fluid and/or methane (Jenner and Lamadid, 2013). Most water used is locked away underground and never returned to the natural hydrological cycle. Impacts on water quality have a potential to impact on contamination of groundwater aquifer layers with either the fracking fluid used to dislodge gas, or the methane gas itself (which is of course poisonous). As you will see from the following map of Great Britain this shows drilling sites and aquafers. See figure 3. Also, to be considered is the potential surface discharges of contaminated produced water (water drawn from the formation to initiate production, which flows to the surface for life of the well) and flowback water (predominantly fracturing fluids, which comes to surface after fracking is completed and before production begins) from shale gas production that could contaminate natural surface waters. Not only is this a risk to public health but also the biodiversity or loss of biodiversity in the relevant environment. A permit, under the Environmental Permitting Regulations 2010 (EPR), from the Environment Agency is required where fluids containing pollutants are injected into ground, where they may enter groundwater. To date there is no evidence that such a contamination has occurred in any site currently in Great Britain, but is it only a matter of time before an “accident” does occur which will affect the biodiversity of that area.

Figure 3.(a) Map of UK showing location of onshore wells drilled for exploration or production and productive aquifers. (b) Map of UK showing location of potential shale gas and oil reservoirs and productive aquifers. Aquifer base map reproduced with the permission of the British Geological Survey. ©NERC. All rights Reserved. (Davies et al. 2014).

High pressure injection of water into shale formations has been linked to seismic events in Lancashire which will be discussed later.

Public participation and consultation has become fundamental for energy regulators due to the intensity and immediacy of public engagement. The intense media scrutiny and broader public knowledge, as well as increased public organizations (local action groups) and the development of social media have contributed to improved citizen communication and often made local issues national and international (Zillman at al. 2015). This has resulted in public demonstrations against fracking in each local community to which fracking licensing have been granted. It would seem that much of public opinion is against fracking.

The Infrastructure Bill (Jan 2015) originally said there would be a ban on fracking in National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and Sites of Special Scientific Interest and introduced mandatory Environmental Impact Assessments. But just eight months later, a major U-turn on this commitment has placed some of the country’s most sensitive and precious wildlife sites at risk by excluding SSSIs from the ban and allowing licences for underground activity in highly protected wildlife sites.

2.4 Controls currently in place.

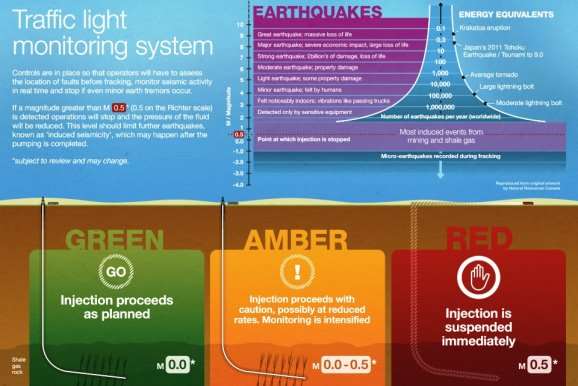

In the UK, the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) followed the recommendations of the joint report of the Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering and developed a ‘stop light’ protocol whereby thresholds for different acceptable levels of seismicity are defined, and if a level is breached during the hydraulic fracturing process the entire operation is to be terminated (DBEIS 2017). This procedure was implemented after seismic activity in Preston in the Lancashire shale gas area. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.Infographic: Seismic activity traffic light monitoring system (DBEIS 2017)

Chapter 3: Comparison of Fracking planning procedures for two Counties

3.1 Current fracking in the UK

In January 2017, the House of Commons produced a Briefing Paper titled, Shale gas and fracking, which states that there has been recent approval of two planning decisions in Lancashire and North Yorkshire suggesting that commercial fracking is getting closer.

3.2 Nottinghamshire County Council

Further public consultation is required before Nottinghamshire County Council’s Planning and Licensing Committee can consider a planning application for an exploratory shale gas well-site on land off the A634 between Barnby Moor and Blyth.

Dart Energy is seeking planning permission to undertake exploratory drilling for shale gas at the site, known as Tinker Lane. The application is for exploratory drilling, to check the suitability of the rock for shale gas extraction.

Nottinghamshire County Councillors will consider the county’s second planning application to undertake exploratory drilling for shale gas at the Planning and Licensing Committee meeting on Tuesday 21 March.

The application was submitted by Dart Energy in May last year to drill one exploratory vertical well 3,300 metres deep and three sets of groundwater monitoring boreholes on land off the A634 between Barnby Moor and Blyth

The application is not seeking permission to carry out any hydraulic fracturing, known as ‘fracking’. The application site, which is currently open farm land, is around one mile north of Barnby Moor and 1.5 miles south east of Blyth.

Permission is sought for a temporary period of up to three years, with the drilling taking place for approximately four months. The County Council has received over 800 representations from the local community and a petition. (NCC)

3.3 Lancashire County Council

On 1 April and 27 May 2011 two earthquakes with magnitudes 2.3 and 1.5 were felt in the Blackpool area. These earthquakes were suspected to be linked to hydraulic fracture treatments at the Preese Hall well operated by Cuadrilla Resources Ltd. Thus, operations were suspended at Preese Hall and Cuadrilla Resources Ltd were requested to undertake a full technical study into the relationship between the earthquakes and their operations.

Cuadrilla submitted to DECC a synthesis report with a number of technical appendices on 2 November 2011, and published this material on their website. These reports examine seismological and geomechanical aspects of the seismicity in relation to the hydraulic fracture treatments, along with detailed background material on the regional geology and rock physics. They also estimated future seismic hazard and proposed recommendations for future operations to mitigate seismic risk.

Further information supplied by Cuadrilla in the course of this assessment is available as Annexes below. The independent experts have now made recommendations to DECC for mitigating the risk of induced seismicity resulting from continued hydraulic fracturing at Preese Hall, Lancashire and elsewhere in Great Britain.

(OGA 2017)

3.4 Organisation responses; Igas and Caudrilla

3.5 General public and conservationist’s responses (Wildlife Trust etc.)

Chapter 4 : Discussion

4.1 Comparison of the two counties policies and procedures.

4.2 Proposed further exploration sites and possible impacts, compensation etc.

Interpretation of the literature generally and in relation to the two counties. Analogy with mining and the collapse of the industry in the UK. Political party in government and their views.

Limitations of the study

Chapter 5 : Conclusion and Suggestions for further research

A summary. Critically evaluate the dissertation. Is there enough protection for wildlife conservation? Recommendations for further research.

REFERENCES

Carbon Brief. 2013. Carbon Briefing: what does extracting shale gas mean for the local environment?Science. Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/carbon-briefing-what-does-extracting-shale-gas-mean-for-the-local-environment.

Davies, R.J., Almond, S., Ward, R.S., Jackson, R.B., Adams, C., Worrall, F., Herringshaw, L.G., Gluyas, J.G., and Whitehead, M.A. 2014. Oil and gas wells and their integrity: Implications for shale and unconventional resource exploitation. Marine and Petroleum Geology. 1-16.

Delebarre, J., Ares, E., and Smith, L. 4 January 2017. House of Commons Library Briefing. Number 6073. Shale gas and fracking.

Evans, D., Stephenson, M, and Shaw, R. 2009. The present and future use of ‘land’ below ground. Land Use Policy 26S. S302-S316.

Finkel M.L., and Hays J. 2016. Environmental and health impacts of ‘fracking’: why epidemiological studies are necessary. J Epidemiol Community Health. Vol 70. No 3.

Great Britain. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (DBEIS). 2017. Guidance on fracking: developing shale gas in the UK [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/about-shale-gas-and-hydraulic-fracturing-fracking/developing-shale-oil-and-gas-in-the-uk. [Accessed: 27 February 2017].

Great Britain. Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). 2013. Oil and gas: onshore exploration and production [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/oil-and-gas-onshore-exploration-and-production. [Accessed: 28 February 2017].

Great Britain. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). 2015. 2010 to 2015 government policy: sustainable development. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-sustainable-development/2010-to-2015-government-policy-sustainable-development#issue. [Accessed: 7 March 2017].

Great Britain. Environment Agency (EA). 2017. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/environment-agency. [Accessed: 15 March 2017].

Great Britain. Oil & Gas Authority (OGA). 2017. Exploration and Production Onshore. [Online]. Available at: https://www.ogauthority.co.uk/exploration-production/onshore/. [Accessed: 15 March 2017].

Great Britain. The Royal Society and The Royal Academy of Engineering (RS & RAE). 2012. Shale gas extraction in the UK: a review of hydraulic fracturing [Online]. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/policy/projects/shale-gas-extraction/2012-06-28-shale-gas.pdf. [Accessed: 7 March 2017].

Jenner, S. and Lamadrid, A.J. 2013. ‘Shale gas vs. coal: policy implications for environmental impact comparisons of shale gas, conventional gas and coal on air, water and land in the United States’, Energy Policy, 53, 442-53.

Jones P., Hillier D., and Comfort D. 2015. Contested perspectives on fracking in the UK. Geography. 100. Part 1.

Small. J. QC. 2013. Fracking Liability. The Estates Gazette; Sutton. 92-94.

Stringfellow, W.T., Domen, J.K., Camarillo, M.K., Sandrillo, W.L., and Borglin, S. 2014. Physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of compounds used in hydraulic fracturing. Journal of Hazardous Materials. Volume 275, 37-54.

- a Ecological Engineering Research Program, School of Engineering & Computer Science, University of the Pacific, 3601 Pacific Avenue, Stockton, CA 95211, USA

- b Earth Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

Zillman, D.N., Lucas, A., and Beirne, S. (2015) 2014: An eventful year for energy law and policy, Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 33:1, 82-105

Zillman, D.N., Lucas, A., and Beirne, S. (2015) 2014: An eventful year for energy law and policy, Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 33:1, 82-105

Zillman, D.N., McHarg, A., and Bradbrook, A. 2014. The Law of Energy Underground: Understanding New Developments in Subsurface Production, Transmission, and Storage. [eBook type]. Oxford Scholarship Online. Available from: NTU Library One Search. [Accessed: 9 March 2017]

BBC Politics. 2016. Fracking moratorium rejected by MPs. [Online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-30993915. [Accessed January 2017].

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/498160/160204_FINAL_letter_to_Mineral_Planning_Authorities.pdf

Impact Assessment – http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2016/384/resources Accessed 27 February 2017

Briefing – Arrangements for fracking operations clarified. 2015. Planning, , pp. 32.

APPENDIX 1.