Hip Fracture Treatment in Older Patients

1.1 Background

Hip (neck of femur) fractures are a common, serious and well-defined injury affecting mainly older people. As global populations age, projections for hip fracture numbers over the coming decades will rise. Delays to surgery are associated with increased post-operative complications, prolonged recovery and length of stay (LOS), and with increased morbidity and mortality (Trpeski, Kaftandziev, and Kjaev, 2013). In addition, the cost burden of hip fractures is substantial. The process of caring for people with hip fractures is complex, long, and involves several diagnostic, therapeutic and administrative activities. These activities occur in A&E and orthopaedic departments, operating theatres, and in the community. They involve a range of health professionals and support staff. When this coordination fails, patients may suffer from avoidable delays and suffering. In the United Kingdom (UK), the bed occupancy rate for hip fractures was more than 1.5 million days, which represent 20% of the total orthopaedic beds (Compston et al., 2009). The lifetime risk of sustaining a hip fracture in the UK from age 50 is around 11% for women and 3% for men (Van Staa et al., 2001). Many of those who recover suffer a loss in mobility and independence: approximately half of those previously independent become partly dependent, while one-third become totally dependent (Myers et al., 1996).

1.2 Current Process

Watford General Hospital (WAT) treat 450 patients for hip fractures every year. Hip fractures are one of the most common complex trauma problems orthopaedic surgeons’ face. Patients are often seriously ill, elderly and frail, which can result in poor outcomes.

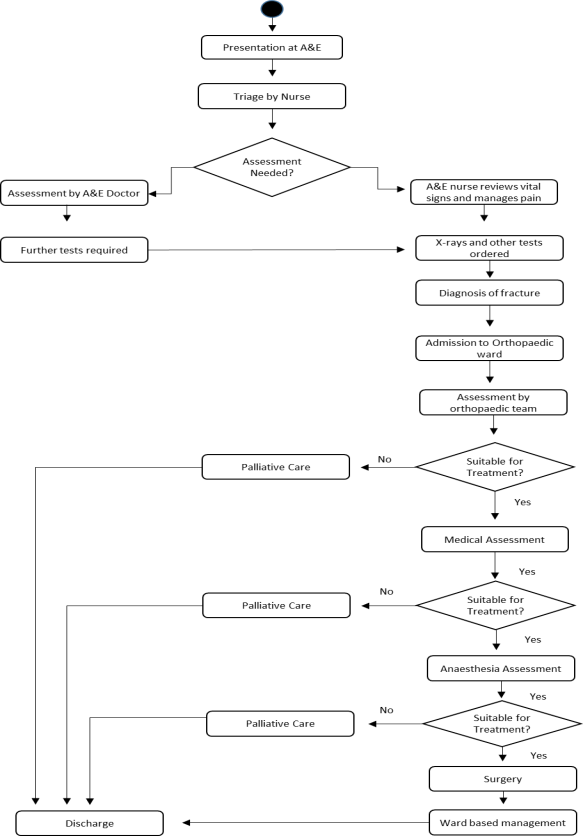

Hip fractures generally result from a fall, patients present at A&E where imaging tests are used to make a diagnosis and pain medication is administered (Appendix A). When possible, patients are moved from the emergency department to a ward.

Ideally, patients will have surgery within 72 hours of arrival at hospital, provided they are in a stable condition. A pre-operative assessment is carried out to establish the patient’s overall health to make sure they are ready for surgery. They also have an anaesthetic assessment. Two main types of anaesthesia are used: general anaesthetic and spinal or epidural anaesthesia. A team of healthcare professionals will perform the surgery, including an orthopaedic surgeon.

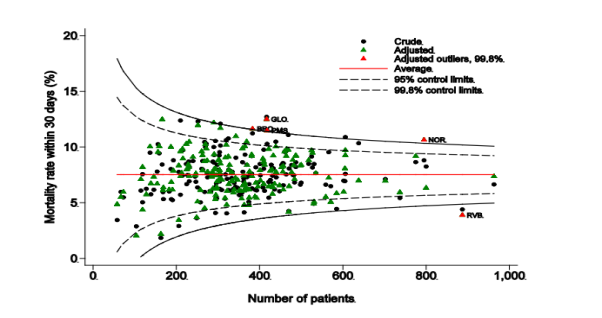

The National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) produce an annual report that includes an analysis of 30-day mortality rates for hip fracture patients who are over 60 years old within the UK. WAT were alerted by the NHFD that they were an outlier, with 12% mortality over 3 years. In the UK the overall mortality rate within 30 days of hip fracture in 2014 was 7.5%Â (Johansen, 2016). High mortality rates are a signal to hospitals that they should investigate to identify and resolve quality issues.

Figure 1Funnel Plot of Crude and Adjusted Mortality Rates 2014 (Source: Johansen, 2016)

Effective strategies are needed to reduce the burden on healthcare providers and to improve patient quality of life and outcomes after a hip fracture. Staff at WAT want to develop an action plan to analyse performance and instigate improvement programmes. This included questioning what elements of care could have been delivered better to ensure that high-quality care is delivered throughout the patient’s treatment, to improve 30-day mortality rates and functional outcomes for patients.

1.3 Perceived Issues with the Current Process

In the present study, the incidence and mortality and functional outcomes in hip fracture patients was studied. The relationships between admission and treatment times, pain management drugs and anaesthesia, and their effect on the patients length of stay (LOS) in hospital were assessed and the following issues were found:

- Admission time from A&E to treatment is high

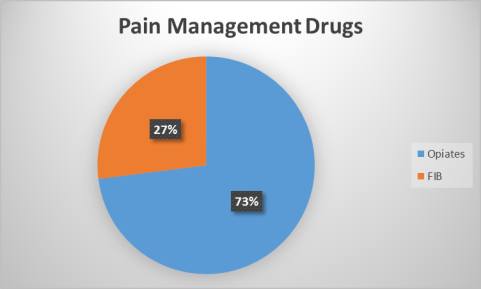

- High level of opiate usage to manage pain

- Routine use of general anaesthesia

1.4 Value Adding Activities

- Admission to surgery times

- Pain management

- Days spent in hospital

1.5 Scope

Older people with hip fractures aged 60 or over are in scope for this project.

1.6 Problem Statement

30-day mortality rates for older hip fracture patients at Watford General Hospital have been 12% for 3 consecutive years, 4.5% higher than the national average (NHFD).

1.7 Goal Statement

Reduce 30-day mortality rates in older hip fracture patients to 8.5% by the end of June 2017.

2.1 Process Map

2.2 Process Narrative

The person arrives at the A&E department by ambulance or car. The triage nurse assesses the patient’s condition. Patients are classified by severity of injury (red, yellow, or green). Patients presenting with suspected hip fractures are commonly assigned a yellow classification, which indicates an emergency but not of a life-threatening nature. An A&E doctor or nurse checks the patient’s vital signs, records their pre-fall health condition, and administers pain medication (generally opiates). Subsequently, in consultation with an A&E doctor (if available), several basic tests (blood tests) and X-rays (hip and often chest) are ordered and performed. The patient is transferred to the radiology department for x-ray. The A&E doctor or nurse then reviews the test results. If a hip fracture is diagnosed, the patient is deemed admissible and an intravenous (IV) drip is started. The patient is transferred to the orthopaedic ward for admission when a bed becomes available. Admission times are currently 13.4 hours.

On admittance to the orthopaedic ward an orthopaedic surgeon will review the test results. If the patient is deemed suitable for treatment the medical assessment team will assess if the patient has any existing medical issues that may affect treatment. If pre-existing medical conditions with the potential to affect treatment are found patients are referred to palliative care and discharged. If no pre-existing conditions are found patients are assessed by the anaesthesia team. Patients deemed suitable for surgery are placed on the trauma list, surgery generally takes place within 72 hours. Patients deemed unsuitable are referred to palliative care and discharged. Patients go to theatre, they are anesthetised using general anaesthetic and receive surgery. They are subsequently transferred back to the orthopaedic ward for ward-based management. Patients are discharged once they are mobile.

2.3 Identification of Problems, Weaknesses, and Change Areas

- High level of opiate use by A&E staff for pain management

- Admission times of 13.4 hours

- Surgery wait times of up to 58.6 hours

- Routine use of general anaesthetic in surgery

3.1 Key Strategic Elements for Improvement

Patients with hip fractures often require complex and challenging care, this is provided by a number of professionals in several departments, crossing a number of service boundaries. These patients are often frail, and their outcomes depend on how effectively their care pathway is managed. Pain management medications, avoidable delays, anaesthesia choices and post-operative care affect functional outcomes and mortality.

The key strategic elements towards improving outcomes for older hip fracture patients are:

- Reducing morbidity and mortality rates

- Achieving better functional outcomes for patients

- Increasing discharge rates to original place of residence

- Increased value from the healthcare budget

They can be achieved by:

- Altering pain management practices

- Altering anaesthetic management

- Reducing admission and treatment times

3.1.1 Pain Management

Despite recent advances in the care of hip fracture patients, significant morbidity and mortality persists. Some of this is attributable to the pain medication administered in hospital. Opiates are the preferred pain management drug at WAT currently (Appendix A). Opiate use can cause nausea, constipation, and confusion (delirium) in the older patients (Coruhlu and Pehlivan, 2016).

Effective pain management is a primary goal in hip fracture treatment. Research suggests fascia iliaca compartment blocks (FIB) is an alternative for pain management in hip fractures. Intravenous opioid therapy is used frequently (Appendix A). However, opioid side effects, such as nausea, vomiting and delirium, are common. Regional analgesic techniques have been shown to provide similar analgesia to opioids. FIB is reported to effectively block cutaneous lateral femoral and femoral nerves in adults (Nie et al., 2015). Studies have suggested superior analgesic effect with pre-operative FIB. They provided superior analgesia to intramuscular morphine in a randomised controlled trial of hip fracture patients (Callear et al., 2016).

FIB is a safe and simple technique that can be administered by junior doctors and specialist nurses with training (Hanna et al., 2014). FIB administered in A&E provided significant decreases in pain when compared to opiates. Post block analgesic requirements for patients in the FIB group were minimal. A study conducted by Callear and Shah (2016) concluded that a single dose of FIB given in the pre-operative period significantly reduced the post-operative and total analgesic requirements in the hip fracture patient. Patients also experience lower rates of delirium and were discharged faster. This reduces the cost of providing inpatient hospital beds and improves quality of life for older patients.

3.1.2 Anaesthetic Management

Anaesthetists have an essential role in the preoperative, operative and postoperative management of hip fracture patients. Complications arising from anaesthesia in hip fracture surgery is influenced not only by the type of anaesthetic used, but also by patient comorbidities and the delays between admission and surgery.” Approximately 25% of hip fracture patients display at least one episode of cognitive dysfunction during hospitalisation” (Heyburn et al., 2012). A systematic review published by SIGN (2009), suggests that the use of spinal anaesthesia may reduce the incidence of postoperative confusion.

3.1.3 Time to Surgery

At present admission times are 13.4 hours (NHFD statistics show the national average is 9.3 hours) and surgery wait times are 58.6 hours. Current guidelines recommend surgery to be carried out within 24 hours of injury (BOA, 2014). Observational studies suggest better functional outcomes, shorter hospital stays, duration of pain, and lower rates of complications and mortality are achieved by performing surgery earlier. Pre-operative delays increase mortality and, in those who survive, prolongs post-operative stay. For every additional 8 h delay to surgery after the initial 48 h, an extra day in hospital results (Colais et al., 2015). Currently WAT fall far short of the ideal to provide optimal care for hip fracture patients.

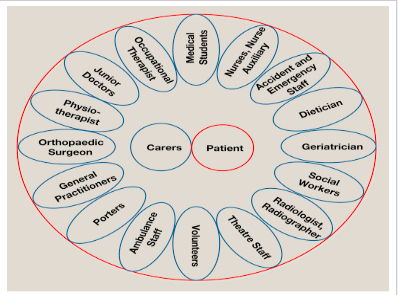

3.1.4 Multidisciplinary Approach

The management of hip fractures requires complex, connected care from presentation at A&E, through all departments. A study of 116 patients found that dedicated nurse specialists are effective at fast-tracking hip fracture patients to surgery by securing hospital beds, organising care, operating theatre lists and acting as a liaison with all other relevant departments (Larsson and Holgers, 2011).

Many published guidelines recommend a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of hip fractures, in addition to, a good care environment to promote best outcomes. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN, 2009), the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2013), and the British Orthopaedic Association in cooperation with the British Geriatric Society (BOA, 2014), have all produced guidelines supporting a multidisciplinary team approach to deal with hip fractures in older people.

Figure 3 Multidisciplinary Team (Source: Orthopaedics and Trauma)

Rieman and Hutichson, (2016) “It is recognised that a team approach with excellent communication between all the members is essential. The multidisciplinary team looking after hip fracture patients is large (Figure 2), and each role is important in the jigsaw of care”.

3.1.5 Clinical Pathway

Clinical pathways should be used to aid the multidisciplinary team. They provide a description of the expected interventions and outcomes throughout the patient journey following a hip fracture. The use of clinical pathways ensures everyone knows the next step in the process and this minimises unnecessary variations in practice (Chudyk et al., 2009). A study of 1193 older hip fracture patients conducted at 6 hospitals in the Limburg trauma region of the Netherlands concluded that the use of a multidisciplinary clinical pathways (MCP) for patients with hip fractures tends to be more effective than usual care (UC). Time to surgery was significantly shorter in the MCP group when compared to the UC group. The mean length of stay was 10 versus 12 days. In addition, the MCP group had significantly lower rates of postoperative complications (Kalmet et al., 2016).

3.2 Proposed Strategy

- Establish a designated Hip Fracture Unit within the main orthopaedic unit.

- Appoint a multi-disciplinary team to be based on the ward comprised of:

- Physio /Occupational Therapist

- Orthopaedic /Orthogeriatric Doctor

- Specialist Hip Fracture Nurse

- Nursing staff

- Establish a Hip Fracture Pathway.

- Establish a protocol-driven, fast-track admission of patients with hip fractures through A&E

- A&E bleep specialist hip fracture nurse

- FIB administered by nurse for pain management and patient centred care

- Patients are admitted to the hip fracture ward within 6 hours

- Appropriate, medically fit patients receive surgery within 24 hours

- Use of spinal anaesthesia when appropriate

- Continuous tracking/live data systems that regularly update patient and logistical data may improve management by identifying patients’ location, delays in treatment and relevant clinical information.

3.3 Potential Process Improvement Tools

3.3.1 Continuous Quality Improvement

Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) is a quality management tool that encourages all members of the health care team to continuously ask, “How are we doing?” and “Can we do it better?” (Edwards et al., 2008). It focuses on improvement for the patient and the practice by asking questions like, can we do things more efficiently? Can we be more effective? Can we do it faster? CQI uses a structured planning approach to evaluate the current processes and improve those processes to achieve the desired outcomes.

Tools commonly used in CQI help team members identify the desired clinical or administrative outcome and the evaluation strategies that enable the team to determine if they are achieving that outcome. The team can adjust the CQI plan based on continuous monitoring of progress through an adaptive, real-time feedback loop (NLC, 2013).

A CQI approach can help improve patient care. “There is a strong link between organisations with explicit CQI strategies and high performance” (Levin, 2016).

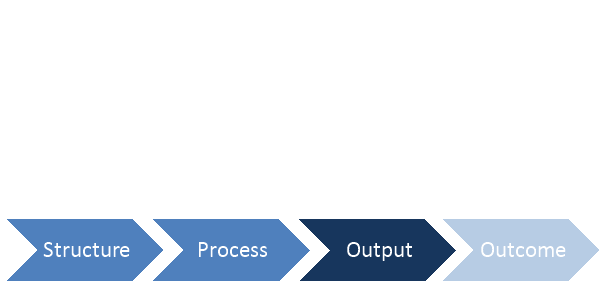

Figure 4 CQI Framework Model (Adapted from NLC)

Structure – examines the characteristics of resources, staff and consultants, physical space, and financial resources.

Process -Â the activities, workflows, or tasks carried out to achieve an output/outcome.

Output – the immediate predecessor to a change in the patient’s status. Not all outputs are clinical e.g. business or efficiency goals.

Outcome – the end result of care. Can be change in the patient’s current and future health status.

Feedback Loop – represents its cyclical, iterative nature.

3.3.2 Lean Management

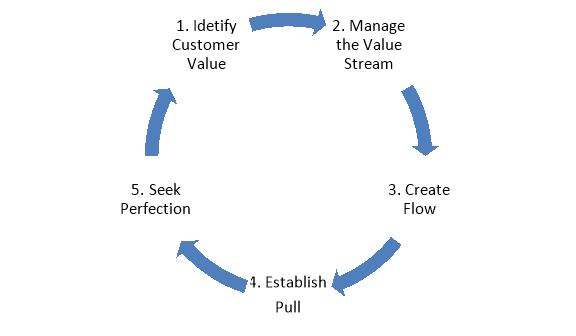

Lean is a process improvement method developed by Toyota in the 1950’s. Lean management principles have been used in manufacturing for many years, however, these principles can be used in healthcare too. According to Womack and Jones, there are five key lean principles: value, value stream, flow, pull, and perfection. Lean drives out waste so that all work adds value from a customer perspective. Lean thinking focuses on how efficiently resources are being used, it looks at each step in the process and asks what value is being produced? Value from a patient’s perspective can be defined as timeliness of treatment, reduced stress, or better functional outcomes. The NHS defines value as “anything that helps treat the patient. Everything else is waste” (Jones and Mitchell,2006).

Identify customer value – in healthcare value is any activity that improves the patient’s health.

Manage the value stream – the value stream is the patient’s journey. Identify process that deliver value to patient’s.

Create Flow – align processes to facilitate the smooth flow of patient’s and information

Establish Pull – provide care on demand and utilising resources effectively.

Seek Perfection – optimise the process through continued development and adjustment to meet patients’ needs.

Optimal delivery of high-quality care to reduce mortality in hip fracture patients is an achievable goal. There are numerous opportunities to enhance the quality of care: reduced length of stay, reduced institutionalisation, reduced mortality and better functional outcomes for patients. Better quality care minimises treatment delay, promotes recovery and facilitates a speedier discharge. Cost and quality are not in conflict – providing high quality hip fracture treatment is a lot cheaper than poor quality treatment. Lean inspired and clinical pathway related process improvement efforts make inconsistent and inefficient practices in health care more visible. The implementation and adherence to evidence based standards will considerably improve the care and management of older patients with hip fractures, this will result in significantly improved outcomes for patients and the healthcare system.

5.1 Appendix A

BOA (2014) BOA standards for trauma (bOASTs). Available at: http://www.boa.ac.uk/publications/boa-standards-trauma-boasts/ (Accessed: 5 December 2016).

Callear, J., Shah, K., Hospital, J.R. and Oxford (2016) ‘Analgesia in hip fractures. Do fascia-iliac blocks make any difference?’, BMJ Quality Improvement Reports, 5(1), pp. 210130-4147. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u210130.w4147.

Chudyk, A., Jutai, J., Petrella, R. and Speechley, M. (2009) ‘Systematic review of hip fracture rehabilitation practices in the elderly’, Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation., 90(2), pp. 246-62.

Colais, P., Di Martino, M., Fusco, D., Perucci, C.A. and Davoli, M. (2015) ‘The effect of early surgery after hip fracture on 1-year mortality’, BMC Geriatrics, 15(1). doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0140-y.

Compston, J. (2009) ‘Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men from the age of 50 years in the UK’, Maturitas., 62(2), pp. 105-8.

Coruhlu, O. and Pehlivan, S. (2016) Worst pills. Available at: http://www.worstpills.org/includes/page.cfm?op_id=459 (Accessed: 5 December 2016).

Edwards, P., Huang, D., Metcalfe, L. and Sainfort, F. (2008) ‘Maximizing your investment in EHR. Utilizing EHRs to inform continuous quality improvement.’, JHIM, 22(1), pp. 7-12.

Hanna, L., Gulati, A., Graham, A. and Corporation, H.P. (2014) ‘The role of Fascia Iliaca blocks in hip fractures: A prospective case-control study and feasibility assessment of a junior-doctor-delivered service’, International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/191306.

Heyburn, J., Holloway, G., Leaper, E., Parker, M., Ridegway, S., White, S., Wiese, M. and Wilson, i (2012) ‘Management of proximal femoral fractures 2011’, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 67(1), pp. 85-98.

Jones, D. and Mitchell, A. (2006) Lean thinking for the NHS. Available at: http://www.nhsconfed.org/~/media/Confederation/Files/Publications/Documents/Lean%20thinking%20for%20the%20NHS.pdf (Accessed: 11 December 2016).

Kalmet, P.S.H., Koc, B.B., Hemmes, B. and ten Broeke, R.H.M. (2016) ‘Effectiveness of a Multidisciplinary Clinical Pathway for Elderly Patients With Hip Fracture: A Multicenter Comparative Cohort Study’, Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation, 7(2), pp. 81-85.

Levin, D. (2016) Using continuous quality improvement to improve patient experience. Available at: http://bivarus.com/using-continuous-quality-improvement-improve-patient-experience/ (Accessed: 7 December 2016).

Myers, A.H., Palmer, M.H., Engel, B.T., Warrenfeltz, D.J. and Parker, J.A. (1996) ‘Mobility in older patients with hip fractures: Examining Pre…: Journal of Orthopaedic trauma’, Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 10(2), pp. 99-107.

NICE (2013) Falls in older people: Assessing risk and prevention. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg161 (Accessed: 5 December 2016).

Nie, H., Yang, Y.-X., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Zhao, B. and Luan, B. (2015) ‘Effects of continuous fascia iliaca compartment blocks for postoperative analgesia in patients with hip fracture’, 20(4).

NLC (2013) Continuous quality improvement (CQI) strategies to optimize your practice Primer provided by. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nlc_continuousqualityimprovementprimer.pdf (Accessed: 7 December 2016).

Rieman, A.H.K. and Hutichson, J.D. (2016) The multidisciplinary management of hip fractures in older patients. Available at: http://www.orthopaedicsandtraumajournal.co.uk/article/S1877-1327(16)30025-2/fulltext (Accessed: 5 December 2016).

Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network part of NHS quality improvement Scotland SIGN management of hip fracture in older people (2009) Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign111.pdf (Accessed: 5 December 2016).

Simunovic, N., Devereaux, P. and Bhandari, M. (2011) ‘Surgery for hip fractures: Does surgical delay affect outcomes?’, 45(1).

Trpeski, S., Kaftandziev, I. and Kjaev, A. (2013a) Fast-track care for patients with suspected hip fracture. Available at: http://www.injuryjournal.com/article/S0020-1383(11)00002-7/fulltext (Accessed: 10 December 2016).

Trpeski, S., Kaftandziev, I. and Kjaev, A. (2013b) ‘The effects of time-to-surgery on mortality in elderly patients following hip fractures’, Prilozi (Makedonska akademija na naukite i umetnostite. Oddelenie za medicinski nauki)., 34(2), pp. 115-21.

Van Staa, T.P., Dennison, E.M., Leufkens, H. and Cooper, C. (2001) Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Available at: http://www.thebonejournal.com/article/S8756-3282(01)00614-7/fulltext (Accessed: 5 December 2016).

Verhelst, J., Dawson, I., Paul T. P. W. Burgers, Esther M. M. Van Lieshout and Piet A. R. de Rijcke (2013) ‘Implementing a clinical pathway for hip fractures; effects on hospital length of stay and complication rates in five hundred and twenty six patients’, 38(5).