Impact of Affirmative Action Policies

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

- BACKGROUND

Throughout the world, various forms of social segregation create different sects of people who live as minority groups within national boundaries. A minority population is an often socially and economically disadvantaged and discriminated group of people. Discrimination is not only a social and moral issue, but also an economic issue. According to a report[1] by the Center for American Progress in 2012, workplace discrimination causes a loss of $64 billion every year as a result of reshuffling 2 million American workers due to some form of discrimination. Similarly, a report[2] published by The Atlantic in 2013 concludes that gender discrimination may have reduced India’s annual growth rate by almost 4% over the past 10 years. Likewise, according to a report[3] published by the World Bank in 2014, homophobia and discrimination cost the Indian economy $30.8 billion every year. The resulting concerns of economists and others have led to the worldwide development and widespread use of “Affirmative Action” (AA) policies designed to prevent societal discrimination of historically disadvantaged groups. Economists have suggested various ways to ensure that those minorities’ rights are protected, not only so that they can become equal and productive members of societies, but also to ensure that resource allocation in the society is more efficient. Affirmative action (AA) policies are one of those policies which have been widely used around the world. Such policies are designed to ensure that the historically disadvantaged groups of people do not suffer any discrimination in their societies by enacting policies which favor those who tend to suffer from discrimination. Such policies are often referred to as “positive discrimination” policies and have been enacted in India to protect some of the social, ethnic and religious minorities. In this dissertation, I analyze the impact of a particular AA policy, political reservation, on the education, and health outcomes of a targeted minority group, the Scheduled Caste (SC), in India.

The concept of AA appeared in the United States as early as 1865, but the term “affirmative action” was first coined by President John F. Kennedy when he signed Executive Order 10925 on March 6, 1961. The executive order was issued to promote actions that discourage discrimination by ensuring that government contractors “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and employees are treated fairly during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” A few years later in 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued another Executive Action (#11246) requiring federal and state employers to “take affirmative action to hire without regard to race, religion and national origin” (sex was added to the anti-discrimination list in 1967).

Affirmative action policies in the U.S. have been arguably successful. AA in the U.S. applies to workplace and in college admission. The Supreme Court has been involved a few times in rulings pertaining to affirmative action policies. One of the first cases was Regents v Bakke (1978) when the Court upheld the AA policy of using race as one of the factors for college admission. However, the Court also ruled that defining specific quotas is illegal. Similarly, Grutter v Bollinger (2003) Supreme Court ruling also favored the use of race on college admission process. Despite some of the successful court cases, affirmative action in the U.S. remains a contested issue with the Fisher v. Texas (2013) case being the latest related case discussed in the United States Supreme Court. The general successes of AA in the Court have resulted in better outcomes for minorities. According to a report published in 2011 by the Americans for a Fair Chance, there has been an increase in college enrollments of people of color by 57.2%. Similarly, the proportion of women earning bachelor’s degree has also been steadily increasing. Likewise, according to statistics from the National Center on Education Statistics, 65% of African American high school graduates immediately enrolled in college in 2011 compared to just 56% in 2007- that number went from 61% to 63% for Hispanic graduates. These improvements in enrollments are attributed to the AA policies.

A different form of AA policy had been enacted in India in 1950, 11 years before the U.S implemented AA to address the rights of African American communities. Before the civil rights movement started in the United States in 1955, India had already implemented a reservation system (a form of quota-based affirmative action) in its 1950 Constitution, to address the issue of discrimination against its minority populations. Minorities in India mostly originate from the social stratification produced by the caste system, which is a key component of Hinduism. Since over 80% of the Indian population identify as Hindu (Census of India, 2011), the caste system has resulted in a large minority group. One of these minorities is identified as the “Scheduled Caste” (SC)[4] by the Government of India and they form about 17% of the Indian population (Census of India, 2011). Several articles of the Indian Constitution introduce the non-discriminatory laws. For example: Article 16(2) of the constitution states that “No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, be ineligible for, or discriminated against in respect or, any employment or office under the State.” Another subsection of Article 16(4) states that “Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favor of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.” Similarly, Article 46 states that “The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes (SC) and the Scheduled Tribes (ST), and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.” The provision for the political reservation/quota comes from Article 334(a), which states that “Reservation of seats and special representation to cease after ten years notwithstanding anything in the foregoing provisions of this Part, the provisions of Constitution relating to the reservation of seats for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes in the House of the People and in the Legislative Assemblies of the States.” It is important to note that the reservation of political seats for different minority groups under Article 334(a) was supposed to expire in 1960. However, the 8th amendment of the Constitution extended the provision for an additional 10 years. Since then, it has been extended several times by the 23rd, 45th, 62nd, 79th and 95th amendments. The 95th amendment extends the political reservation for the minority groups until January 26th, 2020.

Even though the quota system in India has been in place for over sixty years, the social and economic standings of the SC and ST population have not dramatically improved. Over the past few decades when India saw rising economic growth, the poverty levels among the SC population continued to grow despite various measures taken by the State and Federal governments to help the poor population.[5] Many studies have pointed out that, over the past two decades, the SC population has seen a growing incidence of poverty, poor education outcomes, higher levels of unemployment, higher childhood mortality, and declining rates of consumption shares (Thorat, 2007; Teltumbde, 1997 & 2004). There have been supporters and critics of the quota system but the policy has seldom become a national political conversation. Politicians are unwilling to debate the issue since it would be a controversial political move and the media and the public are cautious about discussing it, likely because arguing to replace the system with something else might be seen as being “anti-minority”.

However, the quota system has generated interest among social scientists and economists over the last decade. The primary question of interest has been “how successful has this program been?” “Success,” however, has been variably defined by different economists. Some economists have studied the system’s impact on poverty (Chin & Prakash, 2011; Bardhan, Mookherjee & Torrado, 2010) and others have looked at the overall transfer of wealth from higher castes to lower castes in society (Mitra, 2013). Economists have also studied the political reservation’s impact on policy making (Pande, 2003 and Madhok, 2013). Additionally, some economists have focused on the system’s impact on crimes and atrocities against minorities (Prakash, Rockmore & Uppal, 2015). All of these papers conclude a positive impact of political reservation on several groups of minorities in India. However, when it comes to the impact on the Scheduled Caste, there has been a varying conclusion. This dissertation tries to cement more conclusive evidence about the impact of such laws on the Scheduled Caste.

The primary focus of this dissertation is the education, and health outcomes of the SC group- one of the minority groups that the law targets (ST is the other group). Since the 1950 Constitution of India did not specify a measure of the law’s “success”, the true measure of “success” comes from the intent of the law in the first place. The political reservation is considered to be a constitutional support to those who are deprived of adequate opportunity and equal treatment from the rest of the society. In other words, it was put in place so that it could lift the socio-economic status of the lower caste (including the SC) population in the society. Various studies[6] show that some of the most important issues to improve the socio-economic status of minorities are education and health, among other areas. In fact, in his book Development as Freedom, published in 1999, Dr. Amartya Sen highlights the importance of education and health as indicators and instruments of human development. Sen argues that development stems from freedom and freedom stems from social opportunities such as better education access and healthcare. Hence, this dissertation studies the impact of the reservation laws on two of those important social opportunity indicators- education and health. [7]

The contribution that my research will have relative to existing literature stems from the specificity of the dependent variables I use. While existing literature has examined the impact of political reservation on poverty, policy implications, crime and wealth transfers, it does not address the impact on the SC population’s education, and health outcomes directly. For example, Prakash & Chin found that the political reservation for SC did not have any impact on the SC’s poverty outcomes. However, there is evidence that the SC quotas have increased transfers from the well-off high caste population to the lower caste population (Pande, 2003). My dissertation makes a contribution by going a step further in the discussion. I empirically test if the political reservations for SC have contributed to better education, and health outcomes for this minority group in India. By providing a definitive assessment of the impact of reservation policies on the specific socio-economic indicators of the minority, this analysis will fill an existing gap and be a significant contribution to development economics literature. As the majority of the SC population falls below the UN’s poverty line, this analysis also has implications for the effectiveness of poverty reduction policies in India.

The rest of this dissertation is organized as follows: Section 2 of this chapter provides an institutional background on the caste system and the political reservation system in India. Chapter 2 discusses the education impacts of the reservation system, outlining the literature review, data, empirical strategy, and the results. Chapter 3 discusses the health impacts of the reservation system, outlining the literature review, data, empirical strategy, and the results. Chapter 4 summarizes the dissertation. The Appendix presents the summary statistic table, the results table, and an alternative approach taken in this paper.

- INSTITUTIONAL SETTING

One of the large minority groups in India originates from a deep-rooted belief in a social-stratification system -the caste system. A caste system is a form of social stratification unique to Hinduism, which groups people hereditarily into distinct occupational divisions. Most Indian languages use the term “jati” for the system of hereditary social structures. The term “caste” comes from the Portuguese term “casta” – which means “race”. It is commonly believed that Portuguese travelers came to India in the 16th century and they were exposed to the race-based social stratification system that was already prevalent in India. Hence, the word “casta” was used – to describe what they saw. The term has since evolved into “caste” and is widely used to describe stratified societies based on hereditary groups not only in South Asia but throughout the world. [8]

The origin of the caste system in the region is still debated among scholars. A Hindu person would explain the origin of the caste system by referring to the Lord Brahma, a four-handed and four-headed Hindu god, whose hands and heads represent the four castes within which people are expected to arrange themselves. Indeed, the earliest written evidence of the caste system comes from an ancient Hindu scripture, Vedas,[9]with references to Lord Brahma. Even though one of the four Vedas, the Rigveda (1500 – 1200 BC), lacks direct reference to the caste system and indicates the importance of social mobility, The Bhagvad Gita[10] (200 BC – 200 AD) highlights the importance of the caste system in the general society. In addition, the Manusmriti, a part of The Bhagvad Gita, specifically outlines the rights and duties of the four castes.

A second set of theory on the origin of the caste system refers to a biological adaptation. According to this theory, people in India simply specialized to their God-given skills and attributes- which, over time, transformed the society into a caste system[11]. However, a more socio-historical theory links the origin of the castes to the Aryan civilization. According to this theory, The Aryans, who arrived in India in 1500 BC from south Europe and north Asia, introduced the caste system as a means to influence and control the local population. By the time they arrived, there were other non-Indian groups already in India, including the Negrito, Mongoloid, Austroloid and Dravidian. In order to secure their political and economic influence in the society, and to separate themselves from the “inferior” local population, the Aryans introduced some social and religious rules wherein specific groups of people would do specific types of work and only the Aryans could be the priests, warriors and businessmen in society. They were able to maintain and enforce this structure because of their strong army. This structure paved the way to the more established caste system that we know today.

A commonly recurring theme in theories about the origin of the caste system, however, involves the idea of division of labor. The caste system simplifies division of labor by dictating that people who belong to different castes are responsible for specific and separate jobs. People would voluntarily assign themselves in doing the jobs that they are good at doing. Over time, this led to a more formal social stratification system. According to the established system, people belong to one of four castes: Brahmin; Kshatriya; Vaisya; Shudra. People may also be born outside of the caste system, in which case they are called Dalits (“untouchables”) and not permitted to join any caste. As with the castes, the Dalits are not able to climb up the social ladder. However, they are part of the Scheduled Caste designation. It is important to note that the caste system only applies to people choosing to follow Hinduism. Brahmins are designated to serve as priests; Kshatriyas as warriors and nobilities; Vaisyas as farmers, traders and artisans; and Shudras as tenant farmers and servants. The hierarchy in the social setting is such that the Brahmins are considered the highest caste and Shudras the lowest caste. Untouchables are assigned no occupational role in the society.

Although a caste designation originally depended upon the kind of job a person did, with time, it became a strictly rigid system in which the caste was assigned at birth and passed down through generations. Each person’s birth assigned caste is unalterable during his/her life and is also unalterable for his/her children, grandchildren, and so on. Even though the beginnings of this caste rigidity are hard to trace, it is believed that it is a product of self-interest on the part of ruling emperors throughout India’s history. However, historical evidence does confirm that India’s caste system was not originally as absolute and rigid as it has become in modern times. In fact the Gupta Dynasty, which ruled India from 320 AD to 550 AD, in addition to the Madhuri Nayaks dynasty, who ruled India from 1559 AD-1739 AD, originated from lower castes. It is important to note, however, that from the 12th century onward, much of India was ruled by Muslims. During the initial Muslim rule, the Hindu population was marginalized up to the point where there were hardly any reported populations of Brahmins and Kshatriyas in northern and central India. The Muslim rule created an anti-Muslim sentiment among the Indian Hindu population which further strengthened the caste system by inspiring Hindus to strictly adhere to the elements of their faith, including the caste system. The British took over India from Muslim rule in 1757 AD, thereby lessening the animosity between the Muslim Indians and the Hindu Indians. Some of the documented anecdotal evidence reveals that the British were able to exploit the caste system as a means of social and political control over India during the initial years of their rule. However, they also identified the underlying discrimination brought upon the lower caste population (mostly Shudras and Vaisyas), and, responsively created some of the initial anti-discriminatory laws for the “Scheduled Caste” population of India during 1930-1940.

Historically, the population of “lower caste” always outnumbered the population of “higher caste”[12]. According to the last census taken during the British Empire (1931), the lower caste represented 54% of the total Indian population. India has never taken a caste-based census since its independence from Britain. However, according to four surveys conducted by the Center for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), New Delhi, between 2004 and 2007, the Brahmins represented about 5% of the national population and Kshatriyas represented 3.46% of the national population. Typically, the Brahmins and the Kshatriyas are considered “higher caste”, but the official “Scheduled Caste” designation only protects the Dalits(untouchables) and some of the Shudra caste population[13] which together represent about 17% of the national population[14]. Even though the populations of Brahmins and Kshatriyas do not represent the majority, they constitute a vast number of public officials and politicians in India. According to the same surveys by the CSDS, Brahmins alone constituted 47% of the chief justices and 40% of the associate justices in India. Even though the representation of higher caste in the upper and lower house of the legislative branch of India has been falling- thanks in part to the quota system- the representation is still disproportionate. Brahmins alone represent about 10% of the Members of Parliament (MPs) and hold a significant proportion of public offices. The higher caste population was able to stay in control of governance and form a “majority” in Indian society because of the better education and increased opportunities that they received by virtue of their birth-assigned social rank. The extent of the opportunities they received was also expanded during the British rule, which is why the Brahmins were able to grab a majority of government positions after India’s independence from the British. Vaisyas, Shudras and Dalits have comprised a significant portion of the Indian minority in governance for decades. Specific tribes and some religious groups (Muslim and Christian, in particular) form the other part of the Indian population and governance minority. Even though discriminating against anyone based on caste is illegal in India, peoples’ belief in the ranking inherent to the system is strong.

The fact that people must remain in their birth-assigned castes for life means that members of the SC population face a significant obstacle in climbing up the economic ladder. Opportunities for obtaining a higher social status, better education, well-paying jobs, and political involvement, do not exist for these groups of people. It is for this reason that the Indian government decided to implement a quota system wherein some seats (and/or positions) are set aside for people of certain minority classes in employment[15], education and in different states’ legislatures. These minority groups are referred to as the “Scheduled Caste” (SC) and the designation is based on the last names they carry. The Indian Constitution of 1950 lists 1108 different last names under the “Scheduled Caste,” making these people eligible for participation in the quota system. The tribal minorities are also protected under the quota system and are referred to as the “Scheduled Tribe” (ST). While the SC classification targets the caste minority and “untouchables”, the ST classification targets the population who live in tribal areas (including forest dwellers). There are 744 different tribes listed in this category under the Indian Constitution of 1950.

The SC population is one of India’s most vulnerable groups despite its growing size. According to the 2011 national census, the SC population was over 201 million, which is about 17% of India’s total population. The SC falls at the bottom of the social and economic hierarchy of the caste system. Long before the 1950 Constitution of India, this group of people was considered to be the class of people who did not deserve the rights and protections granted to the rest of the general population. Because of their position within the caste system, the SC population has experienced persistent discrimination and a lack of opportunities in many socio-economic dimensions. The SC group has been historically deprived of access and entitlement not only to economic and political rights but also to social needs such as basic education, health care, and housing. Historical discrimination and exclusion in access to land, capital, education, and health care have led to high levels of economic deprivation and poverty among the SCs. The lack of job opportunities has resulted in an SC population with an exceptionally high dependence on manual wage labor.

Data[16] shows that SCs have lower levels of job market skills, higher underemployment, and lower wage rates compared to rest of the general population because of the limited, if not excluded, access to capital, land, and education they receive (Saravanakumar & Palanisamy, 2013). According to the National Sample Survey 2011, the average monthly per capita expenditures (MPCE)[17] for SC in rural areas was Rs. 1252 ($18) and in urban areas was Rs. 2028 ($29). However, the remainder of India’s population had MPCE of Rs. 1719 ($25) in rural areas and Rs. 3242 ($47) in urban areas- both values significantly higher than those for the SC’s. Similarly, the Census of India 2011 shows that only 50.9% of total SC households used some form of banking services compared to 59.9% of the non-SC households. The census data also shows that while only 59% of the SC households had access to electricity, 67% of the non-SC households had access. Likewise, the National Sample Survey 59th round (2003) shows that only 43.3% of SC households owed some land compared to 62.2% of the non-SC households.

It is important to note, however, that caste-based customs relating to property rights, employment, wage, and education have been replaced by a more egalitarian legal framework, under which the SC and the untouchables are granted equal access and rights compared to the general Indian population. This egalitarian law was enacted as the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act of 1989. However, despite the legal change, SC’s actual access to income earning assets, such as land and other capital, has barely improved. The caste system has continued to function in the private domain of the economy in modified and changing forms. Empirical studies on labor, education, housing, and health services have revealed the persistence of market discrimination towards lower castes, particularly the Dalits (Thorat & Deshpande, 1999; Action Aid Study, 2005). The studies conclude that such discrimination, despite laws banning it, results in lack of access to fixed capital assets, employment, and human development, which all together culminate in high poverty and deprivation among the lower caste population (including the SCs). Some studies also highlight the exclusionary and discriminatory working of private industrial labor markets (Papola, 2012). It is also important to note, however, that enforcement of anti-discriminatory laws is often neglected, in part, because of the deep-rooted belief in the caste system within the law enforcement and the private domain of the society.

1.2.2 Reservation in State Legislative Assemblies for the Scheduled Caste:

Since this dissertation focuses on the role of political reservation on the well-being of the SC population, it is important to understand the way seats are reserved and changed for the SC. It is also critical to understand the role of elected state legislatures in forming policies that affect education, among other sectors. The political reservation in India applies to all states because of a provision in Article 332 of the Constitution of India (effective January 26, 1950). Specifically, the article mandates representation of the SC (and the ST) in the lower house of the Parliament (the “Lok Sabha”) and State Legislative Assemblies. The numbers of seats reserved for the SC are in proportion to their share of the total population in a state. More specifically, the number of seats reserved for the SC is such that its share of seats in the state assembly is equal to its share of the population according to the last population census. A “Delimitation Commission” is formed after every census is taken. The role of the Commission is to delimit the constituencies for the state legislators based on the new population data from the census. In doing so, the commission revises the number of seats reserved for the SC in each state based on the revised constituencies and the SC’s new population share. This policy rule allows for some variation in the SC political reservation. More specifically, the variations come from the following elements:

- With every new census, the number of reserved seats for the SC changes. The census is taken every 10 years. After the census is conducted, a Delimitation Commission is formed. Members of the committee include two Supreme Court and/or high court judges, the chief election commissioner, and a nominee by the central government of India. One of the tasks assigned to the committee is to update the reserved seats in the Lok Sabha and the State Legislative assemblies based on the newly drawn constituency boundaries. In this duty, the committee is simply matching the reserved seat proportion to the SC population share based on the newest census. Since the total available seats do not change, the committee has to change the SC quota seats to match the proportion to population proportion. Thus, the actual number of reserved seats changes every 10 years.[18]

- Since the number of reserved seats can only be an integer, there is always a difference between the actual SC population share and the reserved seat share. The small variation in the quota comes from the discrepancy between the required number of reserved seats and the number of seats that are actually reserved given that the number must be an integer.[19]

- When the definition of the SC changes, the share of reserved seats changes. The defining Constitution of India (1950) listed 1,108 different last names as belonging to the Scheduled Caste category. However, by 2008, 100 additional last names had been added to the list. The list has been growing with the last addition approved in December, 2015[20]. With each added name, the total SC population and hence, its population share, grows. This, in turn, increases the required seat quota for the SC.

- Year-to-year variation exists because while the SC population size changes every year, the actual reserved seats do not change as frequently. Since the Delimitation Commission assigns the reserved seats based on the most recent decennial census population, but the actual SC population changes yearly (continuously over any time period), there is year-to-year variation in the SC’s quota share.

-

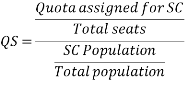

The independent variable of interest, QS (Quota Share), varies from year-to-year because the ratio of reserved seat share to population share changes every year. QS is defined mathematically as:

Given the above definition, most of the variation in the variable comes from the fact that the SC’s population share (the denominator) changes every year while the quota proportion (the numerator) changes less frequently. QS is the variable of interest because the constitution requires the reserved seats to be proportional to the population share of the SC (numerator is equal to the denominator). However, the quota proportion (the numerator) and the SC population proportion (the denominator) are only equal every 10 years when the Delimitation Commission meets to determine the quota proportion that matches the SC population proportion. It is important to note, however, that because of point (ii) mentioned above, the QS variable will rarely equal exactly 1.

Given the above definition, most of the variation in the variable comes from the fact that the SC’s population share (the denominator) changes every year while the quota proportion (the numerator) changes less frequently. QS is the variable of interest because the constitution requires the reserved seats to be proportional to the population share of the SC (numerator is equal to the denominator). However, the quota proportion (the numerator) and the SC population proportion (the denominator) are only equal every 10 years when the Delimitation Commission meets to determine the quota proportion that matches the SC population proportion. It is important to note, however, that because of point (ii) mentioned above, the QS variable will rarely equal exactly 1.

[1] Burns, C. (2012, March). The Costly Business of Discrimination. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2012/03/pdf/lgbt_biz_discrimination.pdf

[2] Jaishankar, D. (2013, March). The Huge Cost of India’s Discrimination Against Women. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/03/the-huge-cost-of-indias-discrimination-against-women/274115/

[3] Badgett, M. . L. (2014, February). The Economic Cost of Homophobia & the Exclusion of LGBT People: A Case Study of India. The World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/SAR/economic-costs homophobia-lgbt-exlusion-india.pdf

[4] Scheduled Caste does not include all of the “lower caste” population. Brahmnin and Kshatriya are typically considered to be “higher caste”; Vaisya and Shudra are considered to be “lower caste”. SC designation only applies to those who are Shudras and who fall outside the caste system, namely Dalits. The caste system is explained in detail in section 2.2.

[5] National Council of Educational Research and Training, 2015

[6] Bloom (2007); Sen (1999)

[7] The Human Development Index (HDI) also adopts education and health as two of the important measures of “human development” in calculating its annual HDI index for various countries.

[8] ushistory.org. (n.d.). The Caste System. In Ancient Civilizations Online Textbook. Retrieved from http://www.ushistory.org/civ/8b.asp

[9] The Vedas are a collection of hymns and poems written between 1500 and 1000 BC in India. This collection is considered sacred in the Hindu religion. The Vedas are composed of four different Vedic texts- the Rigveda, the Samaveda, the Yajurveda and the Atharvaveda. The Rigveda is the largest of these texts, and is considered to be the most important.

[10] The Bhagvad Gita, which is written in the ancient language of Sanskrit, is the most revered Hindu scripture. Even though the origin date of The Bhagvad Gita is still contested, most scholars believe that it was written between the fifth century and the second century BC. The Bhagvad Gita is not a part of the four Vedas.

[11] ushistory.org. (n.d.). The Caste System. In Ancient Civilizations Online Textbook. Retrieved from http://www.ushistory.org/civ/8b.asp

[12] The Brahmins and Kshatriyas are generally considered “higher caste”. However, in most of the surveys conducted only Shudras and Dalits (untouchables) are considered “lower caste”.

[13] Scheduled Caste designation is based on a household’s last name. All of the Dalits fall under this designation as well as some of the Shudras.

[14] The Scheduled Tribe (ST) do not fall under the “Dalit” designation. The STs are protected because of their indigenous heritage.

[15] In federal employment, certain percentage of the hiring is assigned for SC, ST or the OBC.

[16] Data and statistics referred to here come from the following sources: Census of India 2011, The National Commission for Scheduled Castes (2010), Ministry of Human Resource Development (2011), and the Annual Report of University Grant Commission 2010.

[17] MPCE is the per capita final consumption expenditure of good and services by households.

[18] For example: The 2001 census shows that the SC population in Bihar was 13,048,608 while its total population was 82,998,509. Hence the SC formed 15.72% of Bihar’s population in 2001. Once the Delimitation Commission is formed, its job is to match the reserved seats proportion to something close to 15.72% of the total available seats. The Commission finished its job in 2005 when there were 243 seats available in Bihar. Thus, 15.72% of 243 yields 38.20. The committee established 39 SC-reserved seats 2005 (the policy is to round up to the next higher integer).

[19] For example: The ideal number of seats to be reserved in Bihar after the 2001 census was 38.20. However, 39 seats were chosen to be reserved. Thus, there is a variation of 0.80 in the quota.

[20] The addition is mostly due to the demands from several minority groups to be included under SC, so that they can have political representation and other benefits that the SC gets.