Impact of Canine Intervention on Rabies

Problem

Rabies-is a fatal viral disease that causes inflammation of the nervous system, caught from bites or scratches of rabid animals, most commonly domestic-dogs (>95%).[1] Immediate treatment of infected humans with four doses post-exposure prophylaxis decreases chance of developing severe infection, but this is often prevented by availability and awareness of treatment in low-income settings.

Canine-vaccination provides broader benefits for disease-control reducing cases in dogs, human animal-bite injuries, and number of human-cases.[2] While the value of canine vaccination is well-known, local uptake at low-income-settings have been low despite public provision and financing.[3]

Intervention

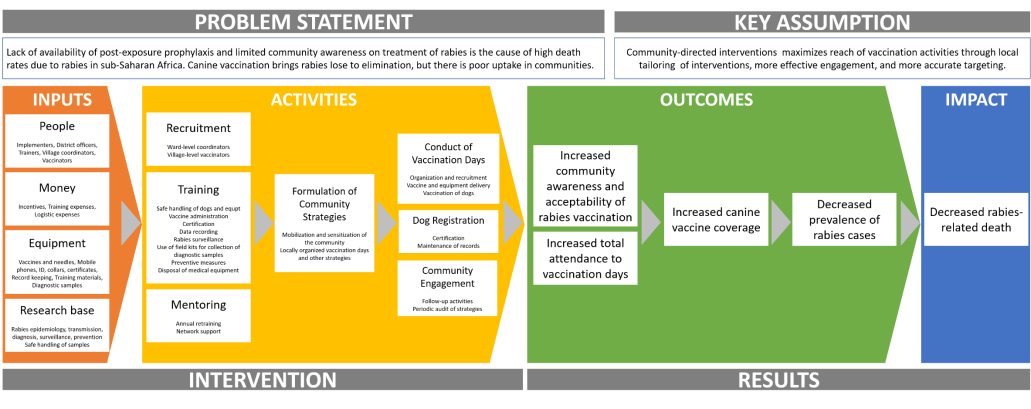

The intervention involves empowering community-health-workers to formulate local-strategies to encourage participation and conduct self-organized rabies-vaccination days, compared against standard of care of centrally-coordinated program. The intervention assumes that low-uptake for current publicly-provided canine vaccination programs is due to locally-inappropriate programs that do not effectively promote awareness and engagement. Community-directed interventions are used in other public health diseases with promising results in improving access to interventions and enhancing efficiency, cost-effectiveness and sustainability.[4] But, its effectiveness for canine-rabies vaccination is-unknown. Community-directed interventions for rabies vaccination is theorized to maximize reach of vaccination activities through localization, more effective community-engagement, and more accurate targeting of potential households.

The theory of change behind the intervention is illustrated by the logic model in Figure 1.

Inputs

The intervention makes use of people, money, equipment, and research base to carry it out. The implementers will tap district officers, train trainors, and recruit village health care workers (HCW, i.e. coordinators and vaccinators). Money will be used for training and logistics, as well the incentives (₤20/month/coordinators and ₤4/day/vaccinators) for the HCW to implement the program. Equipment for training, coordination, vaccination, and monitoring are necessary to conduct the activities. And, all inputs and activities are developed from the research base available. It is assumed that these inputs are adequate and effective in carrying out the intervention activities.

Figure 1. Logic Model

Activities

The inputs shall be used to conduct recruitment, training, and mentoring for the intervention. Recruitment will include development of criteria and guidelines for choosing HCW and actual strategies to reach them. HCW recruits will undergo training on topics such as rabies, safe handling of dogs and equipment, vaccine administration, and prevention as stated in the logic model. They will also undergo mentoring with the research team through annual retraining and network support to motivate the HCW to perform the intervention. It is assumed that HCW are able to understand and internalize their role in rabies prevention, and that the activities will equip them to formulate adequate and effective local strategies to carry out the vaccination and community engagement programs.

Formulation of community strategies is an essential step as it actualizes the intervention’s main assumption. The developed strategies are assumed to effectively sensitize the community towards the vaccination campaign and mobilize the most number of families to participate. This also assumes each individual HCW agrees with and follows the strategy formulated by the group.

The end activity of the intervention is to implement the formulated strategies for conduct of vaccination days, dog registration, and community engagement. Conduct of vaccination days involve local organization and recruitment, logistic management especially for vaccines and equipment, and actual conduct of canine vaccination. The HCWs are expected to conduct dog registrations and maintain an updated record-keeping mechanism. The strategies, being locally owned, are also assumed to go beyond just conduct of vaccination into regular community engagement with follow-up/ supporting activities.

Outcomes

The intervention’s assumption on the value of local mobilization and engagement is expected to contribute towards increased community awareness and acceptability of rabies vaccination. This is expected to increase total attendance to vaccination days, as both frequency and method are dependent on local needs assessment and planning of the group.

Both higher community awareness and attendance to vaccination days are assumed to influence canine vaccine coverage. Higher canine coverage protects the population by decreasing the number of rabid dogs that can infect humans. This would result in the medium term as decreased prevalence of rabies cases in the community. This assumes that the community is able to recognize the signs and symptoms of rabies and seeks diagnosis and treatment to health facilities that are able to diagnose them.

Impact

With less rabies cases in the community, less patients will progress into complications that lead to death, hence reducing rabies-related deaths in the long term. This assumes the community patients are willing to be treated once diagnosed. This also assumes health system reforms on case management nor technological advances in treatment of rabies had no influence in change in mortality.

Objectives

Using the intervention’s logic model, a process evaluation study is proposed with three supporting objectives from a mix of evaluation theories to give more holistic and practical recommendations regarding the results of the intervention. These objectives are as follows:

Table 1: Research Objectives

|

Objectives |

Key areas of concern |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first goal (reflective of implementation theory) was chosen to determine if successful implementation was achieved and can be attributed to the results. The second goal (reflective of intervention theory) was chosen to understand if hypothesized mechanisms-of-change were realized and if other mechanisms have emerged to contribute to the results. The third goal (reflective of realist theory) aims to understand the best mechanisms to attain intended outcomes of the intervention for future reference in similar studies and policy implications.

Evaluation Overview

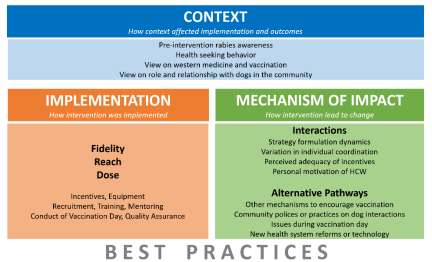

The process evaluation team created a 24-month evaluation plan that will focus on key aspects of the research objectives believed to contribute most to the results in the intervention arm of the research. Figure 2 gives a general overview of the domains, chosen from the assumptions from the logic model.

|

Figure 2. Research Domains

|

Methods

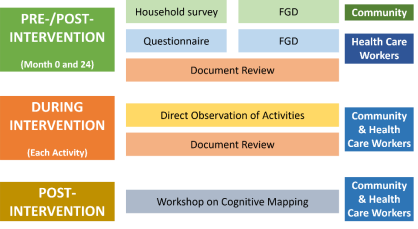

The evaluation will be done in four phases, implemented closely with the timeline of the impact evaluation/research team across 24 months. General methods and target population for the process evaluation are as follows:

Figure 3. Method Overview

At pre-intervention (month 0), questions on knowledge attitudes and practices (KAP) regarding rabies and the community context will be added as rider questions to the researcher’s baseline survey. HCWs will be asked to complete a questionnaire on personal data (economic status), relations with the community (social status), and KAP regarding rabies. Focus group discussions (FGD) will be done with the community to gain deeper insight into the community context that may impact the intervention, and with HCW to assess their perceptions on the interventions. Health system documents (policies, care guidelines, local government initiatives, etc.) will be reviewed to look at changes in care management and technological advances that have taken place.

During intervention (month 1-24), direct observation and document review will be done to assess fidelity, reach and doses of each of the activities during implementation. All of the activities on training, formulation of community strategies, conduct of vaccination days will be directly observed by at least three researchers to understand how interactions take place. Value judgements will have to be agreed by at least 2/3 of the team present during the activity. Conduct of other activities will be assessed from monitoring documents (attendance sheet, accomplishment reports of each HCW, pre- and post-training test results, post-activity feedback forms) from the implementation team.

At post-intervention (month 24), baseline quantitative and qualitative information with be gathered similar to pre-intervention methods to enable assessment of changes from baseline values. The final FGDs with the community and HCWs will also be used as a workshop to create an agreed cognitive map of best practices within the intervention that contribute to its success.

Frequency

Surveys, questionnaires and FGDs are deliberately scheduled only at pre- and post-intervention as the likelihood of the research team influencing both community awareness and engagement through these efforts are high. The third objective of the process evaluation is to look at best context-practice mixes that can be replicated in future runs of the program and conducting these evaluations mid-intervention may act as mediator that will skew the results positively and affect the program and policy recommendations of the study. Direct observation and document review will be done throughout the activities of the intervention to assess conduct of activities taking place.

Sampling

Household surveys coupled to the research will use purposive sampling of community households considering geographic factors and socio-economic status. FGD participants will be chosen using purposive sampling to represent different groups and community areas. For quantitative analysis, all of the data from questionnaires and document reviews will be used during analysis.

Analysis plan

Quantitative aspects of the study will be analyzed through descriptive statistics to show frequency and ranges of responses. Qualitative aspects of the study will be analyzed through causal modelling with mediation and mediator analysis to summarize the responses. Issues and best practices will be determined from post-intervention qualitative analysis using stakeholder cognitive mapping to agree on a generalizable process.

Domains, research questions, research methods, indicators, and frequency are summarized in Table 3:

Table 3. Methods and Indicators

|

Domain |

Research question/s |

Method |

Target |

Indicators |

Frequency |

|

IMPLEMENTATION |

|||||

|

Fidelity |

Was conduct of the intervention activities done as intended? Were adaptations done necessary? |

Direct observation |

HCW |

|

During each activity (training, formulation of community strategy, vaccination days) |

|

What adaptations were perceived to be more successful by the HCW? |

Document – feedback forms |

HCW |

|

After each activity |

|

|

Reach |

Were effective HCW recruited for the intervention? |

Direct observation |

HCW |

|

Combination of observations from training, community engagement activities, vaccination days |

|

How many families were influenced by the community strategies? |

Document – attendance |

Community |

|

Total of all activities during whole of intervention |

|

|

Dose |

Was training new to the attendees/ was there added knowledge gained? Which aspects were delivered successfully? |

Document – feedback forms |

HCW |

|

After each activity |

|

Was knowledge from training accurate and retained? |

Document – test results |

HCW |

|

During initial training and retraining |

|

|

Are the inputs (esp. incentives) and preliminary activities (i.e. training, mentoring) given adequate for HCW to perform their role to the best of their abilities? |

FGD |

HCW |

|

Twice (month 0 and 24) |

|

|

Are the supply of inputs adequate to perform the intervention? |

Document review |

HCW |

|

After each activity |

|

|

MECHANISM OF IMPACT |

|||||

|

Interactions |

Were community strategies developed by HCW unanimously decided and carried out by the individual? |

Direct observation |

HCW |

|

After each activity |

|

Questionnaire |

HCW |

|

Once (month 24) |

||

|

Were incentives, training, and mentoring perceived to be adequate by the HCW? Did personal motivation of the HCW affect their performance of community strategies? |

Questionnaire |

HCW |

|

Once (month 1) |

|

|

FGD |

HCW |

|

Twice (month 0 and 24) |

||

|

Alternative pathways |

Were other mechanisms outside the intervention encouraging awareness and vaccination? Were there other reasons for non-attendance of willing families to vaccination days? |

FGD |

Community |

|

Twice (month 0 and 24) |

|

Household survey |

Community |

|

|||

|

Were there changes in the way the community interacts with dogs not accounted for by the intervention? |

Household survey |

Community |

|

||

|

Did new health system reforms on case diagnosis and management or technological advances in diagnosis and treatment occur? |

Document -policies |

System |

|

||

|

CONTEXT |

|||||

|

What was the community’s level of pre-intervention awareness and engagement in rabies programs? |

FGD |

Community |

|

Twice (month 0 and month 24) |

|

|

What are the health-seeking practices of the community? Do they recognize and seek care for rabies? |

|

||||

|

What are the community views on western medicine and canine vaccination? |

|

||||

|

What are the community views on the role of dogs and their relationship with them? Which views promote taking dogs for vaccination? |

|

||||

References

[1] source

[2] Cite downloaded cleaveland

[3] source

[4] Source, reword since copied from assignment