Mental Capacity and Informed Consent to Receive Treatment

Legal, Ethical and Professional issues surrounding mental capacity and informed consent to receive treatment

Throughout this essay, we will be reviewing and discussing the legal, ethical and professional issues associated with two key aspects of paramedic practice, these are mental capacity and the ability to provide informed consent to treatment and intervention. As the title suggests, the essay will be broken down into three separate sections which will individually relate to the topics in hand. The legal section will focus on how legislation affects the two stated aspects. The professional aspect will cover how mental capacity and informed consent can create professional issues for the paramedic, whilst the final part of the essay will focus on relating the four principles of ethics to the topics which are discussed in this essay. The regulator for Paramedics, the Health Care Professions Council (HCPC) sets out standards of conduct, performance and ethics which states that you must make sure that you have consent from service users or other appropriate authority before you provide care, treatment or other services (HCPC, 2016). There are four principles of ethics will be related to throughout the essay and explanations for these principles are found in appendix A of the essay (UKCEN, 2011).

Legally, it is always necessary to seek informed consent before beginning treatment and intervention, except in certain circumstances which will be detailed later in this essay. The department of health’s guidance on consent states that consent is a ‘general, legal and ethical principle which must be obtained before starting treatment or physical investigation’ (Dept. of Health, 2009). If a clinician were to being treatment/care without the informed consent of the patient, the patient may be able to present a case of battery against the clinician. Most cases where the clinician has failed in the process of gaining consent have been due to not thoroughly explaining risks; this can lead to medical negligence as the recipient of care would not be expecting the associated risks. (Laurie et al, 2016). In legislation in the United Kingdom, there is a standardised examination called the Bolam Test which needs to have its criteria fulfilled in order to prove that medical negligence has taken place. The Bolam test involves a group of peers from the same profession as the clinical reviewing the procedure which the patient may see as being negligent (The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2016). In terms of the paramedic profession, the regulator will provide peers in order to conduct the Bolam test (HCPC, 2016). In some situations, it is very difficult to gain consent before beginning patient treatment, this can be for various reasons such as the patient being unconscious. In this situation, Paramedics/Healthcare providers are able to use the doctrine of necessity which allows them to provide initial life-saving interventions in order to save life/limb when the individual receiving the care is unable to provide informed consent (Hartman K, et al, 1999).

The Mental Capacity act 1983 provides the main legal basis for providing guidance and regulation on whether an individual over the age of eighteen would be seen to have or lack mental capacity, it defines a person who lacks capacity as a person who at the time of assessment “is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain.” (Mental Capacity Act, 2005). The Mental Capacity act was created to safeguard and give power to individuals which may lack the capacity to make informed decisions about care and treatments (Brown M, 2014). The legislation in place provides clear guidance on how to safely identify when an individual lacks capacity and the rights of the individual which lacks capacity. Paramedics use a standardised approach when assessing whether an individual lacks mental capacity, this is known as the two-stage test of capacity (Dept. of Constitutional Affairs, 2007). The first stage of the test involves investigating whether there is cause to believe that there is an impairment in the function of the individuals cognitive functioning. There are many different reasons why there may be a disruption in the functioning of the mind, which can include but is not limited to: Dementia, Head injury, Stroke, Intoxication and learning difficulties (Dept. of Constitutional Affairs, 2007) . Stage two of the mental capacity assessment requires the clinician to evaluate whether the disturbance outlined from stage one causes the individual to be unable to make a specific decision with regards to their treatment, this is assessed by providing the individual with information regarding their condition and then asking them to repeat it at a later time so that the clinician is confident the patient is able to retain the information (Dept. of Constitutional Affairs, 2007). The Mental Capacity Act 2005 contains five principles which underpin the act and must always be applied in the process of evaluating whether an individual may lack capacity, the five principles are explained in more detail in appendix B.

Ethically, when a patient is deemed to not lack capacity, they are then in a position where they may be able to provide informed consent to treatment. For the patient to have informed consent they must have received or have the four components needed to make informed consent. The patient must have the capacity to make the decision. The Paramedic must fully explain the treatment, the side effects of the treatment, the risks of having the treatment and the risks of not having the treatment whilst also explaining the probability of said risks occurring. The patient must fully understand the information that has been given to them by the Paramedic and the patient must then voluntarily give consent to treatment without coercion from a third party such as a relative, friend, or the health care provider (David, 2010). In healthcare, the idea of consent may be sometimes misunderstood as doing what the doctor says which, in modern days, is not the case. There has been debate as to whether consent was sought in the past, due to the fact the patient placed trust in the physician’s beneficence (aim to reduce harm to the patient) and non-maleficence (doing no harm to patients intentionally) and therefore trusted in what the clinician was doing (Habiba, 2000). Beneficence and non-maleficence are two of the four ethical principles.

The assessment of whether someone lacks mental capacity is vital in the Paramedic’s ability to use alternative pathways and referral systems. As Paramedics are highly skilled, autonomous practitioners and work in a variety of out-of-hospital areas, such as public places, patients own homes, and residential care settings, it sometimes proves more relevant to discharge patients from care on scene (Ball, 2005). To do this safely, in a way which will cause no further harm for the patient, the patient must have mental capacity to make their own decisions regarding their care and treatment. The key definition of mental capacity comes from the Mental Capacity Act (2005) which states that capacity is the ability of an individual to make their own decisions regarding specific elements of their life (Mental Capacity Act, 2005). Patients are only able to give informed consent to treatment/intervention if they have mental capacity and therefore it is imperative that Paramedics can effectively assess whether a patient lacks capacity. In assessing whether an individual lacks mental capacity, the paramedic is showing respect for the patient’s autonomy which is one of the four ethical principles.

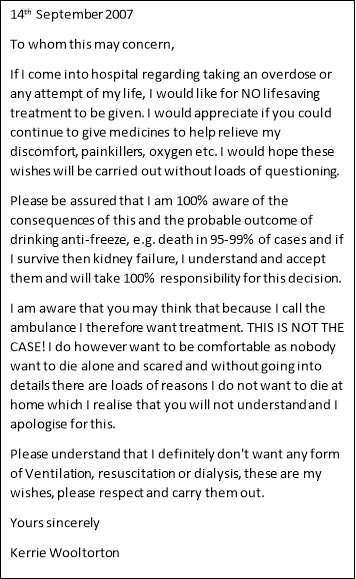

In terms of professional issues, the ability to provide informed consent can seriously affect the way in which Paramedics treat and advise patient. An example of this comes from a 2009 case in which an individual drank anti-freeze and then presented the ambulance crew with a letter, clearly stating that she did not consent to lifesaving intervention but did consent to analgesics in order to comfort her. Through the letter (which can be read and has been annotated in appendix C), the individual displayed she had full mental capacity to make her own decision and also accepted the responsibility for the outcomes of not receiving care (Armstrong W, 2009). In the context of a time critical situation where a decision would need to be made with regards to giving lifesaving saving intervention and withholding it, it can be sometimes difficult for the Paramedic to gather sufficient evidence that the patient (who may lack mental capacity) has created a living will, or that there is an advanced decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) put in place which clearly outlines the patient’s wishes (what they do and do not consent to) when it comes to end of life care. In the absence of this (or absence of any evidence of this) ambulance staff may be forced to act in the patients ‘best interests’. In the context of ambulance staff, the best interests of the patients may be difficult to decide as very little background may be available to the attending paramedic, however if the health care professional is unaware of any ADRT and has taken all reasonable steps in the time available to discover whether an ADRT is in place in the time frame available to them, the clinician making the decision will be protected from liability (Dept. of Constitutional Affairs, 2007). The HCPC states in their standards of conduct, performance and ethics that competent individuals have the right to refuse treatment and that this right must be respected (HCPC, 2016).

Whether an individual is deemed to lack or have capacity can sometimes present similar professional issues to informed consent in terms of paramedic practice. For the individual who lacks capacity, it can be a very stressful time as they may be confused, disorientated or feel as though they have little control over what is happening to them. The Mental Capacity Act states that nobody has the right to deprive someone of their liberty except in situations where they lack capacity and it is necessary to give life-sustaining treatment or to prevent a serious deterioration in their condition. In this situation, any restraint used must be proportionate to the risks to the person from inaction (Mental Capacity Act, 2005). There are no additional rights or authority for paramedics to act in this situation, but if there was cause to believe that there was serious risk to an individual’s life and that they lacked capacity, it would be within the Paramedic’s rights to act in such a way to protect the individual from further harming themselves or provide life sustaining treatment in the event of lack of capacity. Furthermore, the standards of conduct, performance and ethics provided by the health care professions council states that registrants must take all reasonable steps to reduce the risk of harm to service users (HCPC, 2016), therefore if a registrant were to stand aside and allow an individual who lacked capacity to cause harm to themselves or to further deteriorate, they may be at risk of committing an act of omission or even committing wilful neglect which can constitute a criminal offence.

In conclusion, the professional issues surrounding informed consent and mental capacity are applied in every single incident a paramedic may attend and are closely linked. A failure to recognise a lack in mental capacity or gain informed consent may cause detrimental legal and professional repercussions for both the clinician and service user. Although Paramedics are able to seek further advice from sources such as the local police force, senior members of ambulance staff, and general practitioners in order to safeguard their practice, a good working knowledge of the policies and procedures surrounding the issues mentioned in this essay will provide a good basis for gaining informed consent, the assessment of mental capacity and management of service users who lack capacity in the pre-hospital urgent care environment.

Reference List

Armstrong W, (2009) Kerrie Wooltorton Inquest Held 28 September 2009 – Notes of Extracts From Summing Up By Coroner William Armstrong – HM Coroner – Norfolk District (page 1)

Ball L . (2005). Setting the scene for the paramedic in primary care: a review of the literature. Emergency Medicine Journal. 22 (12), p896-900.

Brown M. (2014). Should we change the Mental Health Act 1983 for emergency services?. British Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 3 (3), P114-115.

Department for Constitutional Affairs. (2007). Mental Capacity Act 2005 – Code of Practice. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/497253/Mental-capacity-act-code-of-practice.pdf. Last accessed 11th Mar 2017.

Department of Health (2009). Reference guide to consent for examination or treatment. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

Habiba, M. (2000). Examining consent within the patient-doctor relationship. Journal of Medical Ethics. 26 (5), p183-187.

Hartman K, Liang b. (1999). Exceptions to Informed Consent. Hospital Physician. 6 (3), p53 – 59.

Health and Care Professions Council. (2016). Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. Available: http://www.hcpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10004EDFStandardsofconduct,performanceandethics.pdf. Last accessed 1st Mar 2017.

Health Care Professions Council. (2016). What happens if a concern is raised about me?. Available: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/100008E2HPC_What_happens_if.pdf. Last accessed 8th Mar 2017.

Laurie GT, Harmon HE and Porter G (2016). Mason and McCall Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics (10th Edition). Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Mental Capacity Act (2005) . Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/2. Last accessed 11th Mar 2017.

Sibson, L. (2010). Informed consent. Journal Of Paramedic Practice. 2 (5), p189.

The Royal College of Surgeons of England. (2016). Consent: Supported Decision-Making. London: Professional and Clinical Standards.

UKCEN. (2011). Ethical Frameworks. Available: http://www.ukcen.net/ethical_issues/ethical_frameworks/the_four_principles_of_biomedical_ethics. Last accessed 13th Mar 2016.

Appendix A – The four principles of medical ethics

|

Respect for autonomy |

This principle involves respecting the decision-making capabilities of the service users and providing reasonable assistance in order to make informed choices regarding their care. |

|

Beneficence |

This principle considers the weighing up of the associated risks and costs of treatments against the benefits and likely outcomes. Paramedics should always aim to act in a way which benefits the patient |

|

Non-maleficence |

This principle surrounds the need for paramedics and other health care professionals to avoid causing harm to the individual. Although all treatments involve some level of harm, this should not be disproportionate to the benefits which are as a result of intervention. |

|

Justice |

This principle is about distributing treatments available to each individual fairly and not favouring one service user over the other by means of extra treatments/intervention. |

- UKCEN, 2011

Appendix B – The Five Key Principles of the Mental Capacity Act

|

Presumption of capacity |

This principles states that an individual adult should always be presumed to have full mental capacity until they are proven otherwise. A presumption of capacity should not be made as a result of an individual having a certain medical condition or disability. |

|

Individuals being supported to make their own decisions |

This principle states that individuals should be supported in every possible way to make their own decision before they are deemed to lack capacity. It also means that if it is deemed the individual does lack capacity that they should still be involved in the decision-making process. |

|

Unwise decisions |

This principle states that the individual has the right to make unwise decisions and that the assumption the person lacks capacity should not be made based on a decision. This is due to a difference in cultural values, beliefs and preferences. |

|

Best interests |

This principle states that an individual who lacks capacity is entitled to the decisions which are made on their behalf are done solely in their best interests |

|

Less restrictive option |

This principle states that the individual who makes decisions on behalf of the incapacitated person must make decisions which will have the least effect on the individuals rights and freedoms. |

- Mental Capacity Act, 2005

Appendix C – Kerrie Wooltorton Advanced Decisions Letter

Appendix C – Kerrie Wooltorton Advanced Decisions Letter

– Armstrong W, (2009)