Minor injury and Illness Assessment in the Community

Â

In the following assignment I am going to analyse and evaluate a case of Acute Otitis Media shown in appendix one, by discussing the pathophysiology behind this condition and how important the role of history-taking is as well as, the clinical presentation and the probable examination findings. To further support my findings of the condition I am going to including the special tests that are needed to confirm my diagnosis. Through the utilisation of appropriate evidence, I am going to justify and formulate my treatment plan and referral pathway, taking into consideration the ethical, medico-legal and professional responsibilities relating to the case.

Acute otitis media (AOM) can be referred to as the presence of inflammation in the middle ear with possible effusion, its associated signs and symptoms are rapid in onset (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 27). It is evidenced that more than seventy-five percent of cases commonly affects young children under the age of ten, particularly those who are effected by passive smoking, attend nursery and are formula-fed. It is said to have a greater prevalence in males than females (Edwards and Stillman, 2006, p. 129 -137). Consequently, children have a horizontal, less acute angle and shorter Eustachian tube which makes it easier for bacterial enter and more difficult for fluid to move. However, normally it is collapsed but opens with swallowing and positive pressure (Nair and Peate, 2013, p. 565 -566). The recurrence of this infection can cause serious complications such as hearing loss, tympanic membrane perforation, infrequently it can lead to mastoiditis, facial nerve paralysis, sinus thrombosis, and meningitis (Kivi and Yu, 2016). The presentation in adults and older children is usually reported as earache whereas, young children they may rub and pull on their ear or may present generic symptoms such as fever, continual crying, poor feeding, cough and restlessness at night. Signs and symptoms that are common in AOM consist of red, cloudy or bulging tympanic membrane, pain, pyrexia, headache, tinnitus, nausea and vomiting, reduction in hearing, malaise and otalgia (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015).

Eustachian tube is situated at the anterior wall of the middle ear to the lateral wall of the and therefore, anatomically connects to the throat and palatine tonsil. Thus, allowing the infection to effect anything that is located in the connected pathways. AOM is a common condition that can be triggered by upper respiratory tract infections (twenty-five percent) either via bacteria or viruses (Nair and Peate, 2015, p. 157). Commonly, it is a virus that is responsible for the infection and is usually self-limiting. Although, other inflammatory conditions can have similar outcomes. Inflammation of the can spread up to the medial end of the Eustachian tube, forming stasis which in turn changes the pressure in the middle ear, relative to ambient pressure (Johnson and Hill-Smith, 2012, p. 34 -35). This level of stasis can result in bacteria settling in the space of the middle ear via the straight pathway from the nasopharynx (Nair and Peate, 2013, p. 565 -566). The prominent causes are reflux, blowing something into a body cavity or aspiration. The body’s natural reaction to acute inflammatory responses is recognised as vasodilation, leukocyte invasion, exudation, phagocytosis and local immunological responses in the middle ear (Nair and Peate, 2015, p. 157). It is said that viral based infections that target and harm mucosal linings of the respiratory tract may assistance bacteria’s ability to become pathogenic in the nasopharynx, Eustachian tube and the middle ear cleft. Viral infections have been understood in regard to its part in the pathogenesis of AOM yet, it is still not understood what actual role they play (Waseem, M, 2016). Immunology activity can play a vital role in the occurrence of AOM and its results. The nasopharynx also has an important role in the development of AOM, its lymphoid tissues provide a form of protection against pathogens by obstructing their attachment to surfaces of the mucosa (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015).

There are numerous medico-legal considerations to bear in mind in Anna’s case due to her only being sixteen years of age (appendix one). The fundamental issue is whether she has mental capacity, it is an act designed to protect those who may lack the mental capacity to make their own decisions on their care and treatment. Which applies to individuals aged sixteen and over (NHS Choices, 2015). Individuals have to be given help to make a decision themselves and the information should be in a format that they can understand easily. If someone makes what is believed to be an “unwise” decision, they should not be treated as lacking capacity. Treatment and care given to those who lack capacity should be the least restrictive of their rights and freedoms (GOV UK, 2005). Mental capacity is determined by if there is an impairment, disturbance in the function of their mind or brain, as a result of a condition, illness or other external influences. And by whether theses consequently make the individual unable to make specific decisions when they have to. Individuals may lack capacity to make specific decisions but have the capacity to make others (Quality Care Commission, 2016). It can also fluctuate with time, they may lack capacity at one point in time, but may be able to make the same decision at a later point. To be deemed to have mental capacity they must, understand the information pertinent to the decision, retain the information and use the information in the process of making that decision (NHS Choices, 2015).

The capacity to consent to treatment has a controversial stance in under sixteen year olds. However, Gillick competence expresses that any child under the age of sixteen can consent, if they have “sufficient understanding and intelligence” to be capable of making a decision when required (Ministry of Ethics, 2014). This refers to the assessment undertaken by doctors to establish if a child under sixteen is deemed to have to capacity to consent for treatment in the absence of parental or guardian consent. The routine assessment of competence should be suitable for the child’s age (NHS Choices, 2016). It could be argued, what is deemed to have ‘sufficient’ for understanding and intelligence. In Anna’s case this does not directly apply because she is over that age nonetheless, the transferability is feasible.

Children sixteen and over are deemed to have capacity by law and can consent or refuse treatment. If a child sixteen or over is believed to lack capacity, an assessment of capacity to consent needs to be carried out and documented (Quality Care Commission, 2016). Once valid consent to treatment has been attained it should be recorded as evidence, valid consent is where the medical professional has given the child, parents or both the applicable information about the purpose of treatment, as well as risks and possible alternatives (Department of Health, 2009). It is still good practice to provide parents with information however, consent needs to be sought from the child and the extent of information shared should be deliberated (Quality Care Commission, 2016). In regard to safeguarding concerns, information can be shared with parents without consent. Decisions made in the best interest for the individual, regarding care and treatment can be made anyone involved in caring for them, relatives, friends, and any attorney appointed (NHS Choices, 2016).

As soon as I had consent from Anna or both Anna and her parents I would take a detailed history from her such as, when the pain started, pain score, characteristics of the pain, whether it is radiating anywhere, any allergies, medical conditions, current medication and social factors (appendix one). A thorough history is critical as it helps establish; potential treatment plans, possible safety netting features, rules out red flags or differential diagnosis (appendix two) which are all grounded on the findings from the physical assessment and special tests (Kavanagh, S, 2015). From observation, examination and palpation; it was recognised that her tonsils red and swollen, her head was inclined to right but was walking normally, otoscopy reviled that the tympanic membrane was cloudy and bulging slightly and her palatine and pre-auricle lymph nodes appeared tender (Douglas et al, 2013, p. 297 -314). The baseline observations showed that she had no significant temperature and all others observations were with normal parameters (appendix one). To support my diagnosis and exclude potential red flags indefinitely I would carry out some special auditory tests.

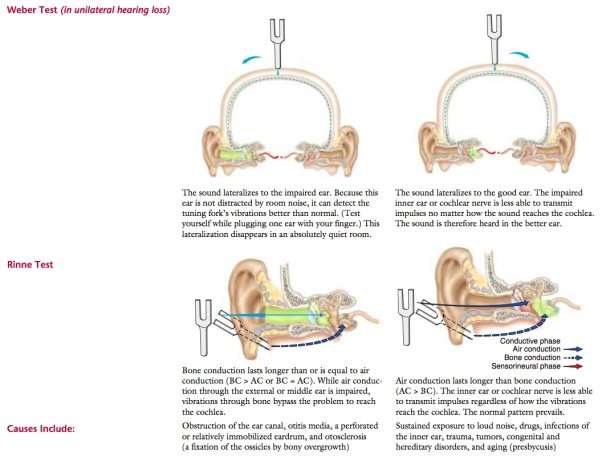

The first type of hearing loss is conductive; this is a problem conducting sound waves along the path of the ear. It can occur anywhere from the outer ear, middle ear or, tympanic membrane (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 11). Sensorineural is the other type of hearing loss, in which the cause is situated in the inner ear, the cochlea or in the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII), (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 11).

A simple test to establish the level of hearing loss is the Voice test. By observing and engaging in conversation with the patient it is easy to recognise if you need to raise your voice to be heard clearly. A whisper test would help you gain greater perception of their hearing loss (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 13). A more complex and effective test that is greatly used is the Tuning fork test (Burkey et al, 1998). Within this there is two further tests, the first is called the Weber test (appendix three). This is where the tuning fork is hit on a surface to make it vibrate, then the base is placed on the middle of the patients’ forehead and then ask the patient where they hear this sound. It is normal for the patient to hear it in both ears except those with conductive hearing loss or unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, then it is better heard in one ear (Douglas et al, 2013, p. 303). The Rinne’s test (appendix three) should conclude that the sound was louder beside the external auditory meatus than on the mastoid process this is because air conduction is greater than bone (Rinne’s positive), (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 13). This test is conducted by placing the vibrating fork on the mastoid process and then the patient reports when they can no longer hear it. The fork is then placed approximately two centimeters away from the external auditory meatus and asked if they can hear it, the patient then reports when they can no longer hear anything (Douglas et al, 2013, p. 303). However, if the patient informs you that the sound is louder on the mastoid process this means bone is the better conductor of sound (Rinne’s negative) and applies to conductive deafness (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 13). A false negative Rinne’s test can occur when hearing is very poor in one side, when the fork is placed on the mastoid process of the poor ear the sound can be conducted through the skull and projected to the good ear (Douglas et al, 2013, p. 303).

To manage people with initial presentations of AOM paracetamol or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for instance, ibuprofen is used to treat pain and fever. It is evidenced that both of them are effective in relieving pain in children with AOM, and have few adverse effects when the suggested doses are used (Nair and Peate, 2015, p. 157).

For the majority of people with AOM a non-antibiotic method is used, this is where they assure patients that antibiotics are not needed and that they make little difference to symptoms. Antibiotics may also have adverse effects and contribute to antibiotic resistance (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 23). A delayed antibiotic prescribing strategy could also be utilised, where they advise patients to commence antibiotics if within four days their symptoms do not improve or if they get substantially worse (Johnson and Hill-Smith, 2012, p. 34 -35). Immediate antibiotics should be given to people that have AOM and are; systemically unwell but admission is not needed, at the risk of complications due to existing diseases, those whose symptoms have continued for four or more days and not getting better, children under the age of two with infection in both ears and children with discharge in the canal or tympanic perforation (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015). A five-day course of amoxicillin is the first-line of treatment if antibiotics are required. Whereas, people that are allergic to penicillin have erythromycin or clarithromycin as alternatives (Munir and Clarke, 2013, p. 23). Amoxicillin is shown to be more effective than erythromycin or clarithromycin against the probable pathogens involved in AOM (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015).

A Cochrane systematic review showed that was no respectable evidence for the routine use of antibiotics in the treatment of AOM in children (Venekamp et al, 2013). Although antibiotics showed to have a statistically significant decrease of children experiencing pain with AOM between day two and seven compared the placebo, eighty-two percent of the children’s symptoms spontaneously improved. It was concluded that the benefits and potential harms of antibiotic treatment must be evaluated, taking into account adverse effects and the possibility of resistance (Venekamp et al, 2013). However, the evidence exposed that they were the most effective against children under two with bilateral AOM, or with both discharge and AOM regardless of age. For the majority of children with mild AOM, an observational method seems acceptable (Venekamp et al, 2013). Another systematic review of the treatment of AOM in children found that compared with short course antibiotics, long courses reduced short-term treatment failure, but had no advantages in the longer term in comparison with short courses (Kozyrskyj et al, 2015).

Consequently, to manage and treat Anna’s AOM I would treat her pain with paracetamol or ibuprofen taking into consideration of any allergies and her asthma.

I would establish if she has taken ibuprofen before and whether there were any problems. The evidence above shows this condition to be self-limiting and that antibiotics have no significant effect in this condition.

It is shown that the public have the most contact with the NHS via general practices, NHS England estimated that approximately one million people access their general practice each day (Comptroller and Auditor General, 2015). The number of direct and telephone contact with patients grew (15.4 percent) throughout all clinical staff in general practices between 2010 and 2015. During that period, the average patient list expanded by ten percent (Baird et al. 2016). It is evident that the non-emergency services like these are being sought by those with conditions that are not serious or life threatening. NHS Direct received roughly 4.4 million calls in 2011 and 2012, 2.7 million calls were made between 2012 and 2013 to NHS 111 and in 2007 and 2008, around 8.6 million calls were received by the GP out-of-hours services (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014).

In Anna’s case of AOM it is evident that she is asymptomatic, the spread of infection has clearly tracked down from the nasopharynx, Eustachian tube, throat, tonsils to the palatine and pre-auricle lymph nodes. It directly corresponds with the physical assessment and the initial history of the conditions presentation therefore, ruling out a differential diagnosis. The no antibiotic framework above is evidently effective, I have concluded that an analgesic (paracetamol) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (ibuprofen) approach would be adapted and advised to manage Anna’s pain. This also demonstrates the importance of history taking as Anna has only had these symptoms for two days, indicating that this treatment is the most appropriate. It is apparent that Anna does not require hospitalisation so I would need to leave her with the appropriate safety netting in place. Thus, if she was at home or at school when the incident occurred and her parents or teacher were present and content with monitoring her, I would leave the same advice as shown above. I would also advice Anna to go and see her GP if her symptoms worsen or persist for four or more days. It is documented that general practices are well-versed in the management of these non-urgent conditions if they develop or worsen. Similarly, it is evidence that the public are aware of which service to pursue if they experience any similar acute conditions. These actions would only be taken once the red flags were ruled out through the tests and assessments conducted above. In summary acute otitis media is usually a self-limiting condition that resolves by itself without the input of antibiotics subsequently, it is likely that Anna will not need any further involvement form any other healthcare professional.

References

(2017). Differential Diagnosis. Available: https://online.epocrates.com/diseases/3935/Otitis-media/Differential-Diagnosis. Last accessed 25-01-17.

Baird, B., Charles. A., Honeyman. M., Maguire, D. and Das, P. (2016). Understanding pressures in general practice. Available: .

Burkey, J, Lippy, W, Schuring, A and Rizer, F. (1998). Clinical Utility of the 512-Hz Rinne Tuning Fork Test. Available: https://www.mm3admin.co.za/documents/docmanager/6e64f7e1-715e-4fd6-8315-424683839664/00023361.pdf. Last accessed 17-01-17.

Comptroller and Auditor General. (2015). Department of Health and NHS England: Stocktake of access to general practice in England. Available: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20151008%20Brief%20guide%20-%20Capacity%20and%20consent%20in%20under%2018s%20FINAL.pdf. Last accessed 27-01-17.

Department of Health. (2009). Reference guide to consent. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/138296/dh_103653__1_.pdf. Last accessed 23-01-17.

Douglas, G., Nicol, F and Robertson, C (2013). Macleod’s Clinical Examination. 13th ed. Edinburgh: Elvsevier. P. 297 -308.

Edwards, C and Stillman, P (2006). Minor Illness or Major Disease? The clinical pharmacist in the community. 4th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 129 -137.

GOV UK. (2005). Mental Capacity Act 2005. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/pdfs/ukpga_20050009_en.pdf. Last accessed 28-01-17.

Johnson, G and Hill-Smith, I (2012). The Minor Illness Manual. 4th ed. London: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd. p. 25 -41.

Kavanagh, S. (2015). History Taking. Available: http://patient.info/doctor/history-taking. Last accessed 28-01-17.

Kivi, R and Yu, W. (2016). Acute Otitis Media. Available: http://www.healthline.com/health/ear-infection-acute. Last accessed 19-01-17.

Kozyrskyj, A., Klassen, T., Moffatt, M and Harvey, K. (2015). Short-course antibiotics for acute otitis media. Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001095.pub2/full. Last accessed 29-01-17.

Ministry of Ethics. (2014). Common Law: Gillick V West Norfolk AND Wisbech Area Health Authority 1984-5. Available: http://www.ministryofethics.co.uk/index.php?p=7&q=2. Last accessed 20-01-17.

Munir, N and Clarke, R (2013). Ear, Nose and Throat at a Glance. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p. 22 -27.

Nair, M and Peate, I (2013). Fundermentals of Applied Pathophysiology: An essential guide for nursing and healthcare students. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. p. 565 -566.

Nair, M and Peate, I (2015). Pathophysiology for Nurses at a Glance. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p.155 -157.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014). NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE SCOPE: Service delivery and organisation for acute medical emergencies. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-cgwave0734/resources/acute-medical-emergencies-in-adults-and-young-people-service-guidance-final-scope2. Last accessed 18-01-17.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2015). Otitis media – acute: Scenario: Acute otitis media – initial presentation. Available: https://cks.nice.org.uk/otitis-media-acute#!scenario. Last accessed 20-01-17.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2015). Otitis media – acute – Summary. Available: https://cks.nice.org.uk/otitis-media-acute#!topicsummary. Last accessed 20-01-17.

NHS Choices. (2015). What is the Mental Capacity Act? . Available: .

NHS Choices. (2016). Consent to treatment – Children and young people . Available: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Consent-to-treatment/Pages/Children-under-16.aspx. Last accessed 21-01-17.

Quality Care Commission. (2016). Brief guide: capacity and competence in under 18s. Available: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20151008%20Brief%20guide%20-%20Capacity%20and%20consent%20in%20under%2018s%20FINAL.pdf. Last accessed 20-01-17.

Venekamp, RP., Sanders, S., Glasziou, PP., Del Mar, CB and Rovers, MM. (2013). Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children (Review). Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub3/pdf. Last accessed 18-01-17.

Waseem, M. (2016). Acute Otitis: Pathophysiology. Available: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/994656-overview. Last accessed 25-01-17.

Appendix 1

Patient: 16-year-old woman called Anna

PC: Pain in right ear

HPC: Anna has had pain in her throat and right ear for the last two days and describes feeling “under the weather”.

SOCRATES- Site– Pain in throat and right ear.

Onset– last 2 days.

Character- sharp pain in ear throat feels “scratchy”.

Radiation– some radiation down towards neck.

Associated symptoms– No systemic signs. Ear feels “full” and patient describes difficulty hearing.

Timing– constant.

Exacerbating/Relieving factors- none.

Severity- 4/10

PMH: Mild asthma, brought on by exertion. Anna had a number of ear infections when she was younger but hasn’t had any for at least two years.

DH: Salbutamol PRN

Allergies: Elastoplast- Contact dermatitis

Alcohol/Smoking: Anna reports drinking occasionally with her friends but does not smoke.

Occ H: Student

SH: Lives at home with her parents and younger brother (12).

O/E:

OBS: T: 37.2C, P: 85 reg, RR: 12, BP: 110/75, SpO2: 98% room air

Walking normally, with head inclined to the right.

Examination of the external ear is normal; palatine and pre-auricle lymph nodes tender; tonsils red and swollen; tympanic membrane cloudy and bulging slightly.

In analyse and evaluate the case by discussing the pathophysiology of the condition and how this relates to the history-taking, clinical presentation and likely examination findings, including any special tests that may be required to diagnose the condition. You should then formulate a treatment plan and referral decision justified by critical analysis, taking the ethical, medico-legal and professional responsibilities of the case into account.

Appendix 2

Differential Diagnosis of Otitis media

|

Disease/Condition |

Differentiating Signs/Symptoms |

Differentiating Tests |

|

Otitis media with effusion |

Typically, the middle ear effusion is asymptomatic. |

On otoscopy these patients have an effusion of any color, air fluid levels, or bubbles with normal tympanic membrane landmarks. |

|

Myringitis |

These patients may have no symptoms attributable to the middle ear. |

On otoscopy there is erythema and injection of the tympanic membrane in the neutral position without other features of otitis media |

|

Mastoiditis |

There is edema, erythema, and tenderness over the mastoid process. |

Diagnosis is clinical based on history and examination. A CT scan may be warranted if symptoms are severe (to exclude abscess formation) or if the diagnosis is uncertain. |

|

Patients may present with painless otorrhea and hearing loss. Opacification of the tympanic membrane may lead to a misdiagnosis of AOM. |

Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical findings. Imaging is rarely necessary. |

(2017). Differential Diagnosis. Available: https://online.epocrates.com/diseases/3935/Otitis-media/Differential-Diagnosis. Last accessed 25-01-17.

Appendix 3

Special Auditory Tests

(2015). Rinne-Weber. Available: http://wikige.wikia.com/wiki/Rinne-Weber. Last accessed 25-01-17.