Providing Healthcare to the Maori

Task 1

a)

In this research, I will project on three hauora Maori trends and paradigms from 1919 to the present day.

The region I choose is Tetai Tonga (south Island).

Hospitalization, alcohol and Diabetes are the three related hauora Maori trends and paradigms I mentioned above.

Traditionally, Maori people have several models of health to approach health as follow:

- Te Whare Tapa Wha

Te Whare Tapa Wha was developed by Mason Durie in 1982 which includes four cornerstones of Maori health: Taha tinana (Physucal health), Taha wairua (spiritual health), Taha whanau (family health) and Taha hinengaro (mental health). Physical health is easy to understand. Spiritual health is just like faith that people believe. They get unseen and unspoken energies from this. Whanau health means the support from wilder social system. Belonging, sharing and caring within the community. In the meanwhile, mental health could not separate from this model. It shows people’s feeling and thought. This four care dimension structure will not useful if it lacks of any dimension. When taking care of Maori, the staff should think of all these four dimensions.

- Te Wheke

Using family, wellbeing, spiritual, mind, physical wellbeing, extended family, life force, identity, breath of life from forbearers and emotion are contributed to waiora or total wellbeing.

Access to primary health service could be seeing a GP, practice nurse, pharmacist or other health professional working within a general practice.

Secondary health service could be cardiologists, urologists and dermatologists, etc. who do not get in touch with patients directly.

All the information is collected and collated in accordance with research methodology defined in the research plan.

b)

In this research, I may use interview, journals and internet as methodologies to gather data.

c)

Literature Review

Hospitalization

Avoidable mortality contains deaths happening to those under 75 years old that might possibly have been avoided through population-based interventions or through preventive and medical interventions at an personal level. Amenable mortality is a sort of avoidable mortality and is limited to deaths from conditions that are amenable to health care (Ministry of Health 1999).

Avoidable hospitalisations mean that hospitalisations of people under 75 years old that drop into three sub-categories:

Preventable hospitalisations: hospitalisations resulting from diseases preventable through population-based health improving strategies

Ambulatory-sensitive hospitalisations: hospitalisations resulting from diseases sensitive to prophylactic or medical interventions that are deliverable in a primary health care setting

Injury-preventable hospitalisations: hospitalisations avoidable through injury prevention.

Alcohol

Maori had not had alcohol until Europeans came. Even dislike it. From the 1850s Maori tried to control access to liquor, proclaiming some communities dry. Some of them hoped that the government could intervene and a lot of laws were passed restricting Maori access to alcohol. The government announced that the King Country dry in response to requests from Ngati Maniapoto in 1884. Maori drinking and alcohol-related convictions reached the same level as those of Pakeha in the 1890s.

By 1948 lots of the controls on Maori access to liquor were removed. Drinking became more common for them as they increasingly moved to the cities.

In the 2000s average daily consumption of alcohol was the same for Mari and non-Maori, but Maori were more likely to binge drink.

Diabetes

Estimated prevalence of diabetes in Maori is about 20%, about 3 to 4 times that of European New Zealanders.

Maori develop diabetes about 10 years earlier than non-Maori. The big increase comes at around the age of 45.

Sourcing:

http://www.hrc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/HRC35brooking.pdf

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/maori-smoking-alcohol-and-drugs-tupeka-waipiro-me-te-tarukino

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470538/

Task 2

Hospitalization

I made an appointment with a local Maori female and had an interview with her to discuss about hospitalisation of Maori.

A few of hospitals did not admit Maori and in the meanwhile a lot of Maori refused to go to hospital. Because in Maori’s opinion, hospitals were the place where you went to die and where you were cut up after death, where a baby’s iho (umbilical cord) and whenua (placenta) were not treated with respect. As a consequence, they would like to stay at home until death.

Also, I searched on the internet to gather some more information.

Before European came, the population of Maori was about 90,000 to 100,000 in 1800s. Fortunately, they were not get infected many diseases that European suffered from.

But after European came and colonized, the health condition of them became worse than before. The population reduced to the lowest level around 42,000 by1891 due to various diseases.

Maori’s access to medical help was limited by the following factors:

The loss of tohunga and traditional medical knowledge through population decline

The lack of hospitals and doctors in the rural areas where most MÄori lived

Maori were refused to admit by some hospitals

The unwillingness of some doctors to treat Maori, and Maori did not have the right to be treated with respect.

Maori women would not like to be examined by male doctors.

Hospitals had been established from the mid-19th century, and at times conditions within them provoked action. When conditions for female patients at Dunedin Hospital caused concern in the late 19th century, women from the local elite formed the Women’s Ward Committee. Their remarkably successful fundraising resulted in the building of a new women’s ward and the introduction of trained female nursing staff (at that time hospital nursing was generally men’s work).

Socio-economic disadvantage could be another reason that made the hospitalization of Maori became low. More than 50% of them live in deprived areas. Financial issue leaded a series problem such as less opportunity to get education. Lack of knowledge might increase the risk to get ill. On the other hand they might feel whakama to see a doctor.

At the present day, hospitals are not allowed to refuse Maori people. And Maori people started adopting the way to see a doctor to be treated with respect.

As noted earlier, a significant proportion of the excess mortality among Maoris stems from diseases for which effective health care is available, suggesting differences in access to health care. In this context, access has been described in terms of both “access to” and “access through” health care, the latter concept taking into account the quality of the service being provided. Health care need and health care quality have been developed into a framework for measuring disparities in access to care in the United States, a framework that includes broader environmental and societal factors (e.g., racism) that may affect access.

There is increasing evidence that Maoris and non-Maoris differ in terms of access to both primary and secondary health care services that Maoris are less likely to be referred for surgical care and specialist services, and that, given the disparities in mortality, they receive lower than expected levels of quality hospital care than non-Maoris. One survey showed that 38% of Maori adults reported problems in obtaining necessary care in their local area, as compared with 16% of non-Maoris. Maoris were almost twice as likely as non-Maoris (34% vs. 18%) to have gone without health care in the past year because of the cost of such care. This adds to previous evidence that cost is a significant barrier to Maoris’ access to health services.

Alcohol

As we all know, drinking could increase likelihood of diseases. Women drank less than man. On the other hand, although South Island women drank more than non-Maori women, they were less likely to drink in a hazardous way. The percentage of South Island women were obese, increasing with a rate of 48% from 2002 to 2003. Drinking does not only cause health issue but also raise the risk of unemployment. They spent money on alcohol, begged alcohol money on the street again and again. Even some of them were sent to the jail due to commit a crime.

|

Indicator |

MÄori |

non-MÄori |

||||

|

Males |

Females |

Total |

Males |

Females |

Total |

|

|

Consumed alcohol in the past 12 months (15-64 years) 2007/08, percent 1, 2 |

88.7 |

83.8 |

86.1 |

88.4 |

82.2 |

85.2 |

|

Drinking alcohol daily in the past 12 months (past year drinkers 15–64 years), 2007/08, percent 1, 2 |

5.2 |

2.7 |

3.9 |

8.4 |

5.8 |

7.1 |

|

Drinking large amounts of alcohol at least weekly in the past 12 months, (past year drinkers 15–64 years), 2007/08, percent 1, 2, 3 |

28.1 |

22.0 |

24.9 |

13.6 |

8.5 |

11.0 |

|

Using cannabis in the past 12 months, (15–64 years), |

32.6 |

23.9 |

27.9 |

16.3 |

9.7 |

12.9 |

The table shows that Maori and non-Maori adults were equally likely to have consumed alcohol in the past year. Maori adults were less likely than non-Maori adults to have drunk alcohol daily in the past year. However, of those who had drunk in the past year, Maori were more than twice as likely as non-Maori to have consumed a large amount of alcohol at least weekly.

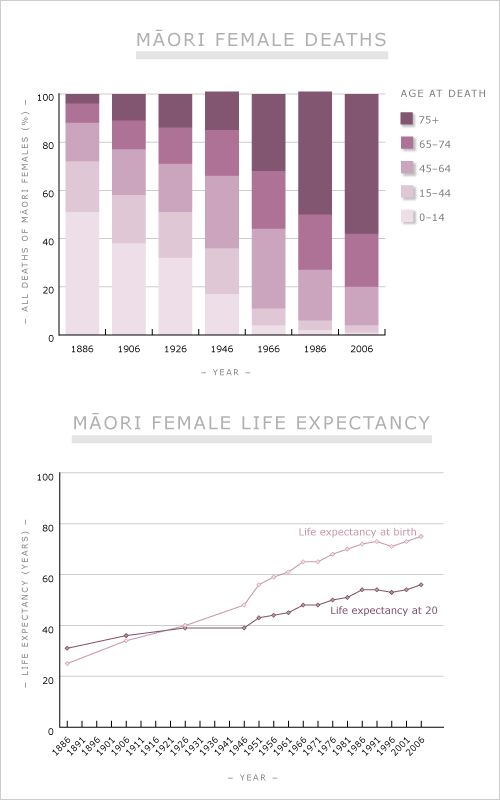

From these two graphs, we can see the comparing of the frequency of drinking alcohol, and of drinking a large amount of alcohol (defined as six or more standard drinks for a man, or four or more for a woman), for Maori and non-Maori men and women. They determine a tendency for Maori to drink less often, but to drink more when they do.

Diabetes

Diabetes is almost three times more common in Maori than non-Maori. In addition, for Maori aged 45–64 years death rates due to diabetes are nine times higher than for non Maori New Zealander for the same age. Maori are diagnosed younger and are more likely to develop diabetic complications such as eye disease, kidney failure, strokes and heart disease.

The estimated average age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes for Maori was 47.8 years in 1996, six years younger than New Zealand Europeans (54.2 years)

The self-reported prevalence of diabetes in 2002/03 was 2.5 times higher among Maori than among non-Maori.

The estimated lifetime risk of being diagnosed with diabetes for Maori in 1996 was more than twice that for New Zealand Europeans.

The disparity in mortality rates is highest in the 45–64 age group, where Maori women die from type 2 diabetes at 13 times the rate of non-Maori women and Maori men at 10 times the rate of non-Maori men.

The proportion of Maori on dialysis for which diabetes was the cause of end-stage renal failure is much higher than for New Zealand Europeans (55% versus 14%)

Maori with diabetes are twice as likely to have a major lesion in the lower limb, requiring amputation, than New Zealand Europeans.

Task3

Disparities in health between Maoris and non-Maoris have been evident for all of the colonial history of New Zealand. Although there have been significant improvements in the past 140 years, recent evidence indicates that the overall gap in life expectancy between these groups is widening rather than narrowing. Explanations for these differences involve a complex mix of factors associated with socioeconomic and lifestyle characteristics, discrimination, and access to health care.

Maori-led programs designed to improve health care access are taking a 2-fold approach that supports both the development of Maori provider services and the enhancement of mainstream services through provision of culturally safe care. The driving force behind the new initiatives described here has been the evidence of the poor health status of the indigenous people of New Zealand and their clear demand for improved health services. Maori provider organizations and cultural safety education are examples of initiatives that have emerged not in isolation but, rather, within a context of macro-level government policies that have been shown to either promote or greatly hinder the health status of indigenous peoples.

Hospitalizing

The health status of indigenous peoples worldwide varies according to their unique historical, political, and social circumstances. Disparities in health between Maoris and non-Maoris have been evident for all of the colonial history of New Zealand. Explanations for these differences involve a complex mix of components associated with socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, availability of health care, and discrimination.

Improving access to care is critical to addressing health disparities, and increasing evidence suggests that Maoris and non-Maoris differ in terms of access to primary and secondary health care services.

Alcohol

Hazardous drinking refers to an established drinking pattern that carries a risk of harming physical or mental health, or having harmful social effects to the drinker or others.

Maori have similar rates of past-year drinking as the total population, but have higher rates of hazardous drinking. Rates of hazardous drinking among Maori adults have decreased since 2006/07, (from 33% in 2006/07 to 29% in 2011/12).

Maori youth drinkers aged 12 to 17 follow similar patterns to adults and are more likely to have ever drunk five or more drinks on one drinking occasion and on average reported a higher level of consumption on their last drinking occasion.

They are less likely to drink at home under parental or guardian supervision. Maori youth drinkers are more likely to have alcohol purchased for them by friends who are over 18 and less likely to receive alcohol purchased by parents They are more likely to purchase their own alcohol.

They are also more likely to agree that ‘it’s ok to get drunk as long as it’s not every day’.

Maori youth are more likely to consider violent/aggressive situations as an aspect of drinking that worries them and other teenagers and are more likely to report being personally affected by or involved

health-related harm such as a hangover, loss of memory, or injury, violent/aggressive situations, spending too much on alcohol and sex/being with girls/guys when drunk.

Diabetes

In summary, type 2 diabetes is a major health issue for Maori. Maori experience higher rates, are more likely to die from type 2 diabetes, and more likely to carry the burden of its complications than non-Maori. Its impact on quality of life for Maori is huge.

Urgent action is required at all levels. Effective strategies to address ethnic disparities in diabetes and diabetes care require a global view, innovative models, partnerships, and accountability to all stakeholders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

2007). Interventions need to have a multi-factor, multi-system, and multi-level approach. The first step to improving diabetes care to Maori is to ensure primary prevention and early detection of diabetes in Maori. Secondly, regional and local services could undertake analyses of access and quality issues in their service delivery to Maori, develop strategies to improve service delivery, and then monitor the effectiveness of those changes. Broader, contextual issues including structural barriers and socioeconomic barriers must also be addressed.

Reference

The New Zealand Health Strategy. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2000.

The Primary Health Care Strategy. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2001.

He Korowai Oranga: Maori Health Strategy. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2002.

Durie M. Whaiora: Maori Health Development. Auckland, New Zealand: Oxford University Press Inc; 1994

http://www.hrc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/HRC35brooking.pdf

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/maori-smoking-alcohol-and-drugs-tupeka-waipiro-me-te-tarukino

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470538/

Order Now