Redundancy in New Zealand: Procedural Fairness and Remedies

Title of the study

Redundancy in New Zealand: Procedural Fairness, Substantive Grounds, and Remedies.

Redundancy has become a normal part of organizational life, researchers are predicting that both the rate and the extent of job losses through redundancy are likely to continue well into the twenty ï¬rst century (e.g. Appelbaum and Donia, 2001a; Cascio, 2002; Dawkins et al., 1999). Generally redundancies within an organisation occur when there is a decline in company revenue and/or work available or the company is looking to restructure and streamline the organisation (Wooden, 1988). In these circumstances the employee may find that their position is surplus to the company’s requirements or needs. Therefore, the organisation or employer will announce to the employee or employees affected that their contracts are going to be terminated as their positions will no longer exist.

Redundancy in New Zealand

In the New Zealand Employment Law Guide (Rudman, 2014) the Labour Relations Act 1987 defines redundancy as “… a situation where … a worker’s employment is terminated by the employer, the termination being attributable, wholly or mainly, to the fact that the position filled by that worker is, or will become, superfluous to the needs of the employer”. Thus, it is the position itself that is made redundant and the decision to make a position redundant should have nothing to do with the particular employee who is filling that position. Redundancies have to be for genuine commercial reasons and not for any other underlining reasons such as capability or performance issues.

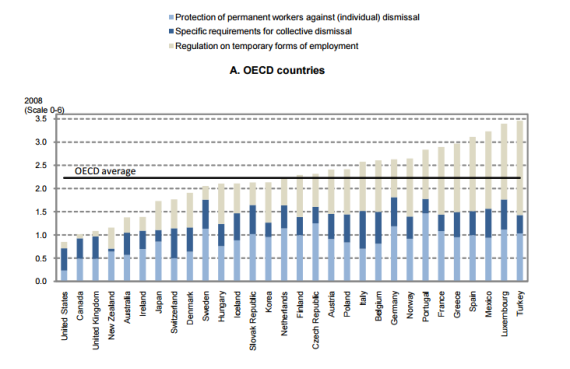

Redundancy is acknowledged within New Zealand’s employment relations system, as it is in many countries. However, in contrast to the majority of foreign jurisdictions, successive governments in New Zealand have decided not to codify the law relating to redundancy and provide definitive protection for employees who face a redundancy situation (Hughes, 2011). Venn (2009) provides a comparison with other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, highlighted New Zealand’s minimal protection for employees in situations involving redundancy. In particular, Venn emphasized New Zealand’s negligible cover in mass redundancy situations. The following figure clearly depicts the limited protection in correlation to the other OECD countries.

Figure 1: Strictness of Employment Protection OECD Countries (Venn, 2009)

Effects of Redundancy

From an organizational perspective, the economic outcomes of redundancy are open to debate (Cascio, 1993; Ryan and Macky, 1998) but it is widely recognized that for the individual, redundancy can lead to a wide range of negative outcomes. Redundancy is frequently associated with ‘diminished psychological wellbeing’, while long-term unemployment can lead to ‘physiological deterioration’ (Leana and Ivancevich, 1987). As Wooden (1988) comments: ‘The concern about redundancy stems from the perception that job loss involves substantial economic and psychological costs for the adversely affected worker and his or her family. The worker made redundant must immediately deal with the shock of job loss.’ For example, redundancy has been found to impact on employees in terms of loss of morale, lowered organizational commitment, withdrawal behaviours such as absenteeism and increased turnover, loss of motivation, mistrust, uncertainty and insecurity (e.g. Brockner, 1988; Brockner, Grover and DeWitt, 1992; Dolan and Belout, 2000; Koslowski et al., 1993; Latack, 1990; O’Neill and Lenn, 1995; Worrall, Campbell and Cooper, 2000).

Waters (2007) study on voluntary and in-voluntary redundancy shows the different attitudes and thoughts employees are feeling when it comes to redundancy. Redundancy can have serious implications for those it has happened to and can be an extremely difficult time during the entire process. Employees fear for the future and responsibilities they have outside of their working life. Employers should let the remaining employees express their anger or frustration and inform them that it is perfectly normal to express their feelings.

Burke (2008) investigates the effects of redundancy during a strong economy and low unemployment rates. Burke says that the number of people experiencing redundancy is surprisingly high. This can come as a shock and be difficult for employees who have been with an employer for a substantial number of years as they are suddenly back in the job market. Looking for a job after so many years of working and competing with thousands of others who have also lost their jobs can be very traumatic. According to Burke, “Being made redundant can have similar emotional effects to bereavement.” People still see a stigma attached to being made redundant and would feel embarrassed or humiliated about being in the situation.

Redundancy also results in a range of negative economic outcomes, including interruption to employment and career paths, loss of income, and potentially ï¬nancial hardship (particularly where it is followed by an extended period of unemployment). Ewart and Harcourt (2000) assessed the effects of a mass redundancy at a New Zealand airline on a group of 139 ground stewards in August, 1991. Findings show that the ground stewards’ post-layoff earnings have declined nearly 40% by 1996, from $50-55,000 to $30-35,000. This was a severe decline than that documented in most studies, in which earnings losses of 10 to 20% were more common and 5 to 10% were not unusual. Ewart and Harcourt identified the primary cause to be the non-transferrable highly specific training and work experiences to the airline industry. Furthermore, ground stewards’ also expressed profound feelings of bitterness post-redundancy as 94% of the respondents thought that the company had handled the dismissals “very inappropriately.”

Those who remain after a period of redundancy are known as the ‘survivors’ and are often described as suffering from ‘survivor sickness’ (Noer, 1993) or ‘survivor syndrome’ (Appelbaum and Donia, 2001a, 2001b; Brockner, 1988). Noer (1993) deï¬nes ‘survivor sickness’ as a term that describes the attitudes, feelings, and perceptions that occur in employees who remain after involuntary staff reductions. Survivors may exhibit a range of emotions including fear, insecurity, uncertainty, frustration, resentment, anger, sadness, depression, guilt, unfairness, betrayal and distrust (Noer, 1996). Redundancy impacts further on the individual through changes to the psychological contract. Rousseau (1995) notes that, ‘redundancy and restructuring have imposed on workers employment arrangements they did not choose’. She suggests that the psychological contract, which the employee originally accepted, changes as organizations restructure and ï¬nds new ways of doing things. In the process of change, jobs are altered but employees do not feel free to renegotiate the contract.

Research Questions

The research questions proposed below are the fundamental core of this redundancy study. It focuses on factors within the redundancy such as procedural fairness, substantive grounds, and remedy. The research questions are as follows:

- To what extent do employers follow procedural fairness?

- To what extent do employers have substantive grounds for redundancy?

- In situations where employers fail to follow procedural fairness and substantive grounds, what are the remedies offered to the employee?