Research Methodology in Education Research

Section Two: Research Design

Chapter Three: Research Design

Introduction

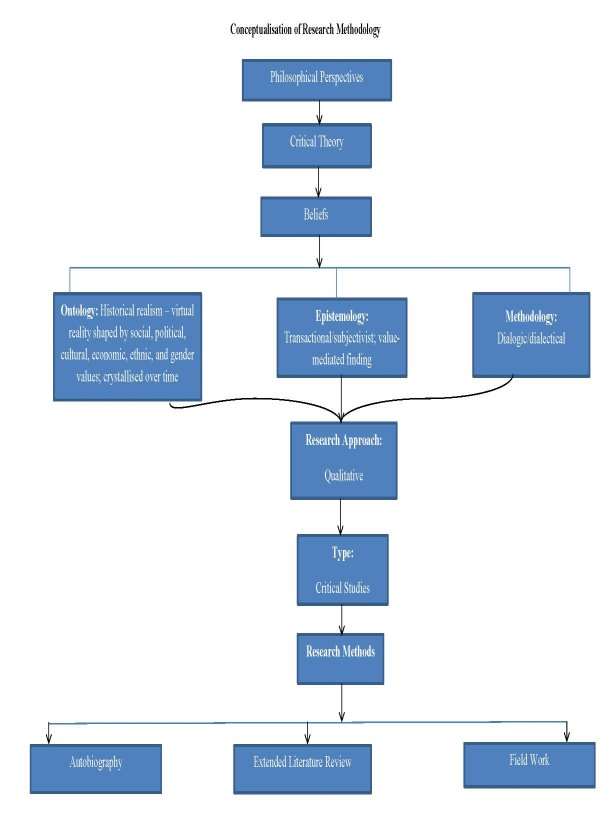

This chapter explains the methodological underpinnings of the study. I provide justifications for the investigative and analytical paths adopted. I discuss the aim of the Critical Theory paradigm and its philosophical positions on epistemology, ontology and methodology in a research enterprise. Also addressed are the people involved, research instruments, data collection procedure, and data analysis.

Figure designed by the researcher

Figure 1

Conceptualisation of Research Design

Philosophical Underpinnings of Critical Theory

The study centres on issues of power, class, privilege and the consequent social relationships. Being aligned with the anti-colonial framework described in Chapter Two, the study is situated within the tradition of Critical Theory. Creswell (2014) puts Critical Theory under the umbrella of a transformative worldview. ToFay (1987), issues of empowerment, irrespective of gender, class, and race, are central to Critical Theory. Lincoln, Lynham, and Guba (2011) state that the research aim of Critical Theory is to critique, seek change and liberate. Per the theoretical framework, the study advocates for Ghanaian H.E to acknowledge and respect African worldviews and perspectives. The study argues that the dominant Western paradigms that shape Ghana’s higher education do not adequately empower the Ghanaian student. This consciousness is necessary to make Ghanaian students a subject of the education experience to help reorient higher education and make it emancipatory.

Table 1 summarises the ontological, epistemological, and methodological beliefs shaped by Critical Theory.

Table adapted from a book source

|

Item |

Critical Theory |

|

Ontology |

Historical realism – reality shaped by social, political, cultural, economic, ethnic, and gender values; crystallised over time |

|

Epistemology |

Transactional/subjectivist; value-mediated finding |

|

Methodology |

Dialogic/dialectical |

Table 1

Basic Beliefs of Critical Theory (Lincoln, Lynham, and Guba, 2011)

Research Approach – Qualitative

A qualitative approach was most appropriate for this research because it offers a better opportunity to provide in-depth understanding of the subject matter. It provided the best avenue to investigate the research questions.

Design – Critical Studies

In line with the philosophical outlook of critical theory, I employ McMillan and Schumacher’s (2010) critical studies framework because my research seeks to find out how privilege, “class”, and power acquired through Ghana’s H.E can be translated to serve societal good. According to McMillan and Schumacher (2010), critical studies design emphasizes ideas like “dignity, dominance, oppressed, authority, empowerment, inequality, and social justice” (p. 347). Researchers employing a critical study design must advocate for and stimulate change.

Methods of Data Collection Employed

McMillan and Schumacher (2010) note that “observation” and “interviews” are common methods employed in critical studies (p. 347). Denzin and Lincoln (2011a) also mention that qualitative research is ”inherently multimethod” (p. 5), albeit there is an imperative to provide sound rationale. Accordingly, I employed autobiography to illustrate my locatedness, a literature review, and face-to-face interviews as methods for this study.

Â

Action Plan

Table designed by the researcher

|

Research Questions |

Data Needed |

Methods |

Analysis |

Purpose |

|

1. What does it mean to be educated in Ghana? |

Lived experience |

Autobiography |

The education environment, teaching, and learning |

How an educated person is recognised in Ghana |

|

2. What are the main features of the historical development of H.E in Ghana? |

Secondary data |

Literature Review |

Historical analysis of the conceptions in traditional African and Western perspectives |

To present the different notions and purposes of H.E traditionally (African), during colonialism and contemporarily. |

|

3. How elitist is H.E in Ghana? |

Primary data |

Fieldwork. Interviews through semi-structured interview guide |

Manually by presenting the themes in the responses |

To explore ways to mitigate the asymmetrical power relationships in H.E |

|

4. What are the alternative means of funding H.E in Ghana? |

Primary data |

Fieldwork. Interviews through semi-structured interview guide |

Manually by presenting the themes in the responses |

Borders on access and de-commercialisation of H.E |

|

5. What are the possible futures of H.E in Ghana? |

Primary data |

Fieldwork. Interviews through semi-structured interview guide |

Manually by presenting the themes in the responses |

Relevance of H.E |

Table 2

Summary of How Research Questions were Answered

Question 1 – What does it mean to be educated in Ghana?

To answer this, I employed my experiences throughout school to illustrate the process of education and consequent characteristics that identify the highly schooled. Autobiography is a reflection on events of the past and a careful presentation of such accounts. Pictures and other artefacts help to illustrate the accounts presented in narratives (see Ellis, Adams & Bochner, 2011). While this method locates me in the study (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010) and offers insights into the broader outlook of H.E in Ghana, it comes with its shortfalls. Autobiography is criticised as “being too artful and not scientific, or too scientific and not sufficiently artful” and self-centred (Ellis et al., 2011, p. 283). Delamont in Ellis et al. (2011) accuses autobiography (as part of autoethnography) as lacking extensive fieldwork. Anderson, in Ellis et al. (2011), contends that the use of personal experience makes autobiography biased.

I acknowledge these inadequacies and the shortcomings of human memory, hence my concentration on events during my university education. Furthermore, for my experience not to appear isolated, I engaged with other autobiographical accounts and literature to support my accounts – to provide rigour. As Ellis et al. (2011) suggest, the credibility of the writer offers reliability in autobiography and the realistic nature of the account is the scale to measure validity. The strengths of autobiography are its ability to “reduce prejudice” on a phenomenon, and “encourage personal responsibility and agency” (Ellis et al., 2011, p. 280).

Question 2 – What are the main features of the historical development of H.E in Ghana?

I employed secondary data (literature) in this regard. According to Neuman (2006), an extended literature review as a method gives the opportunity to explore the vast materials on a study. Literature provides a worthy source of information due to the dynamism and diversities in humanity. It is the basis of building and enhancing knowledge, skills and attitudes – the foundation of education. A literature review grants credibility to the study as a “good review increases a reader’s confidence in the researcher’s professional confidence, ability and background”. To Neuman, an extended literature review locates the study in a framework and “demonstrates its relevance by making connections to a body of knowledge” (p. 111). Further, “a good review points out areas where prior studies agree, where they disagree, and where major questions remain.” In addition, it “identifies blind alleys and suggests hypotheses for replication” (Neuman, 2006, p. 111).

As part of my extensive literature review, I employ the works and speeches of prominent African Presidents and scholars to make a case for the type of higher education that would be meaningful in Ghana. Similarly, I employ academic literature and views of a former Ghanaian President and other political leaders to argue how colonial relations continue to survive in Ghana. Furthermore, I employ proverbs – an embodiment of African oral traditions and culture – as an example of an African knowledge base that can shape H.E. I utilise selected proverbs to argue that H.E in African perspectives promotes the public purpose.

Fieldwork – Questions 3, 4, and 5

Fieldwork is integral to many forms of research – qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. It helps to comprehend and appreciate many social phenomena. Indeed, many academic disciplines are both fields of theory and practice – and fieldwork is also integral. Peake and Trotz (1999) acknowledge the significance of fieldwork: “it can strengthen our commitment to conduct good research based on building relations of mutual respect and recognition. It does, however, entail abandoning the search for objectivity in favour of critical provisional analysis based on plurality of (temporally and spatially) situated voices and silences” (p. 37).

Research Instrument

I used a semi-structured interview guide as instrument to conduct the interviews. This was important to help elicit detailed information on the subject. Interviews are useful to elicit “thick descriptions” (Geertz, 1973) of knowledge and insight into realities. Denzin (2001) describes thick description as “deep, dense, detailed accounts” (p. 98), which provide alternative perspectives to that of the researcher. McMillan and Schumacher (2010) also note that critical studies are multi-method and say, “…observation and interviewing are used most often. The key is to gather the right form of information that will support the advocacy desired” (p. 347-348).

People Involved (Respondents)

The respondents for this study were people who work or had worked within Ghana’s public universities. I had a proxy who helped identify and made initial contact with prospective respondents. I interviewed a retired Professor who is the Chairman of a university council. He has been advocating over the decades for education in Ghana to reflect African culture and worldview. I accepted the recommendation from my proxy to interview him. He is vastly knowledgeable but inclined toward African worldviews. It was important to get such an individual at the apex of university decision-making to offer some insight on the inner dealings of universities. Another respondent was a former Pro-Vice Chancellor of a public university who is on a post-retirement contract. His past role in the university equips him to offer reason why the status quo remains and the difficulties that come with transformation. It is difficult to tell his biases but he does not seem entrenched on specific worldviews.

A former Registrar of a public university who happens to hold a Ph.D was also interviewed because Registrars in Ghanaian universities are in charge of the day-to-day administration of the university, and hence have rich knowledge on the administrative setup of public universities. His strengths lie in administration. There was a traditional ruler (paramount Chief) who happens to be a Professor in a public university. He is predisposed to favour African worldviews and share light on how difficult or easy it is to fuse African worldviews in the university structure. His knowledge and promotion of ancient African history and African American studies indicates his inclinations. The next respondent was a Christian Reverend Minister who is also a Senior Lecturer. His specialization is in Performing Arts and how theatre can be used to develop societies. His works indicate immense African cultural advocacy despite being a Christian priest.

I interviewed a former director of an Institute in a public university (position equal to a Dean). He is a Senior Lecturer in the field of Education and his inclinations are quite difficult to tell. The next respondent is a playwright and Lecturer who prior to his academic life held a top position in an international development agency. He was selected due to his knowledge of Ghanaian developmental issues and his deep insight into African cultural worldviews. Furthermore, I interviewed a respondent with expertise in Development Studies. He is a senior research fellow at the social division of an institute in a public university. Lastly, there was also a linguist and who is interested in African liberation and consciousness. His works and views are very political against the West. He is very knowledgeable in African culture and ancient African history. Cumulatively, the respondents have accrued over 200 years of experience working in universities.

Data Collection/Procedure

I had a proxy in Ghana who agreed to help identify and make initial contact with potential respondents. Though he once held a high position in a public university, he had no power or control over the respondents. After the respondents agree to participate, I liaised with the proxy to arrange a meeting and scheduled the interviews. Prior to the interview, I sent the interview guide to the respondents via e-mail so they could form their thoughts on the issues therein.

The respondents expressed interest in the study and offered lots of encouragement. Even though I desired to interview females, the proxy found it difficult to locate them – they were either busy or out of the country. I scheduled the interviews for an hour but most of them offered more than an hour – two hours in some cases and they were willing for follow-up communication. Some offered references and suggested books that would contribute to the research.

It was daunting and quite intimidating going to interview such high profile personalities. Voices like, “Are the questions going to make sense to them, and do I know enough to engage an intellectual discussion with these people?” kept echoing in my mind. Despite these “butterflies”, I was assured that the questions were shaped by concerns and gaps in literature. I also had it in mind that I was on a mission to learn.

Nevertheless, the process came with obstacles. There were several instances where we rescheduled meetings because the respondents were unavailable. In some instances, they had impromptu engagements so they “sacrificed” our scheduled meeting. The classic experience was driving for about 150km from Accra to another region only to find the respondent chairing a function that closed late. He informed me of his schedule but we both thought the programme would finish early. At the end, he was visibly exhausted and had to drive about 80km home (in another region). He asked me to sleep over and make the 80km to his house the next day for the interview. I made the journey but did not get to see him immediately as there were many people waiting to see him. Eventually, when I had the opportunity to meet him, my lack of traditional knowledge was severely exposed. His elders and members of his council would not entertain English/Western protocols, so I had to fall on the limited Palace protocols I know to navigate that space. He nevertheless was extremely helpful and introduced me to many other scholars. From a Western perspective, these issues border on “power” but the African in me acknowledged that these delays were not intentional, though frustrating and expensive. It was obvious they were busy; besides, I saw their acceptance to participate as a favour as there were no payments or incentives. There is an African proverb that “With patience, one can dissect the ant and see its intestines.”

Data Analysis

To quote Patton (2002), “qualitative analysis transforms data into findings. No formula exists for that transformation. Guidance, yes. But no recipe. Direction can and will be offered, but the final destination remains unique for each inquirer, known only when – and if – arrived at” (p. 432). My data analysis began with the growth of the thesis. In the course of writing the theoretical perspectives and the literature review, some thematic areas began to emerge. The major themes bordered on notions of elitism in Ghanaian/African H.E, a lack of community-oriented values in Ghanaian/African H.E, and the African renaissance and pride. I employed these as pre-determined themes on which I formulated research questions. Therefore the responses were to answer questions that came out of these themes.

I analysed the field data manually by adopting an inductive approach of qualitative data analysis. I transcribed the interviews into text and “separated [it] into workable units” (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010, p. 369). I organised the responses and grouped them under the various research questions and read the transcripts thoroughly to identify comments pertinent to answer the research questions. I highlighted these comments and looked out for new observations and insights that could offer other understandings to the study. I examined the field transcripts to identify emerging themes and patterns, made interpretations out of the themes, and considered them in regard to the literature and theoretical framework. I subsequently present the findings and discussions in anecdotes (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010).

Credibility

Credibility in qualitative studies refers to the extent to which findings and analyses of the study are realistic (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010). To ensure this, I designed the interview guide based on issues raised in literature. In addition, I endeavoured to interview different people with different expertise within the university structure. Though I could not get any respondent from government institutions, the respondents offered worthy responses as some have occupied different positions in government institutions.

A technique I employed to enhance credibility of the study was to send the transcribed interview to the respondents via e-mail for them to confirm the transcription appropriately captured their thoughts. I consequently provide detailed narratives from the respondents. Giving that the respondents did not object to the transcripts, the quotations offered in the analysis chapter of this study reflect the data collected.

Reflexivity

Chilisa (2012) argues that the closeness between the researcher and respondents may affect the truth value of research as it becomes difficult to distinguish between their experiences. In this study, I acknowledge my biases, and clearly illustrate and justify them both in my theoretical and methodological perspectives. The nature of Critical Theory and critical studies makes the issue of reflexivity quite tricky as the research is shaped and designed by biases that must be checked. Being conscious of my biases, I left the selection of respondents in the hands of a third party. Besides, the respondents are established academics who I could barely influence – especially regarding what to say. I also devoted significant space to the voices of the respondents in the analysis chapter to clearly illustrate their thoughts and maintain the truth value of the study.

Though triangulation helps in addressing trustworthiness of qualitative studies, the nature and status of my respondents made triangulation quite impossible. I could not use independent auditors, as suggested by Lincoln and Guba (1985), due to ethical restrictions. However, by sending the transcribed interviews to the respondents to validate, I was able to enhance the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of this study, ensuring trustworthy findings that a reader could transfer and generalise in a similar space.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have outlined the research design used in the research. I have argued that adopting a qualitative approach is appropriate to answer the research questions. Employing a critical studies framework justifies the aim of helping transform social relations between the schooled and unschooled in Ghana. It offers empowerment to students of Ghana’s H.E by offering alternative perspectives to help emancipate the schooled from dominant Western perspectives. Through my proxy, I was able to interview knowledgeable people in Ghanaian universities who offered rich information on how H.E can serve a public purpose. I used the inductive method of qualitative data analysis by highlighting responses that answer the research questions. The emerging themes from responses were synthesised and presented as anecdotes.

In the next chapter, I will describe, using my lived experiences, how the educated individual is constructed in Ghana. My autobiographical approach will indicate how the process of schooling divides society and confers notions of superiority and difference to the highly schooled – a phenomenon the study conceptualise as colonial.