The Problem of Grade Inflation

Â

Grade Inflation: Is A the new C

Quinn, my 9-year-old stepson played on a little league baseball team. He attended most of the practices and played in all the games. I asked one day who won the game today? He looked to his father for the answer. I asked, “doesn’t he know if his team won?” It seems that this little league bent the rules of baseball. Well, they didn’t just bend the rules they made up their own rules – making sure all the players played, no one struck out, five runs and the other team was up…… you get my drift. Then to top it off they held a party at the end of the season where everyone received a trophy. I was frankly appalled. Being rewarded just for participation.

The prevalence of grade inflation is effecting students, professors and institutions. Students are receiving higher grades than earned. A has become the new C. If our educational system is failing to grade appropriately for attainment of knowledge that students supposedly are there to gain, then what does it all mean? It would seem suitable to compare it to giving every person on a sport team a trophy just for participating. It is a deceptive practice and ethically wrong to give a grade when it truly is not achieved no matter what the reason. The purpose of this argument on grade inflation is to convince students, professors, parents and institutions that the practice of grade inflation must stop. Everyone is affected by the strength or weakness and by the fairness or unjust attributes of our educational system. Grade Inflation has many repercussions. Students receiving higher grades make it difficult to discern the average student from the above average student from the exceptional student.

Problem Analysis

In my research, I have found educators agreeing that grade inflation is a problem. Over the past decades claims of grade inflation in American higher education have been ubiquitous, with ample evidence documenting its prevalence and severity (Arnold 2004; Summary & Weber 2012; Carter & Lara, 2016, p. 346). As stated by Rojstaczer 2003, “The data indicate that not only is C an endangered species but that B, once the most popular grade at universities and colleges, has been supplanted by the former symbol of perfection, the A” (p. A21)

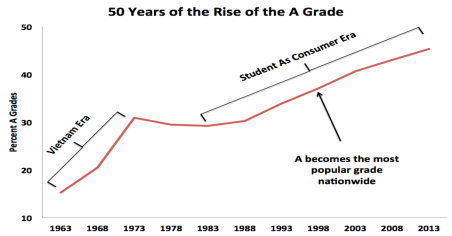

It is important to note the causes of grade inflation in the first place. As stated by Rojstaczer and Healy (2010), “Faculty attitudes about teaching and grading underwent a profound shift that coincided with the Vietnam War (see graph below). Many professors, certainly not all or even a majority, became convinced that grades were not a useful tool for motivation, were not a valid means of evaluation and created a harmful authoritarian environment for learning. Added to this shift was a real-life exigency. In the 1960s, full-time male college students were exempt from the military draft. If a male college student flunked out, chances were that he would end up as a soldier in the Vietnam War, a highly unpopular conflict on a deadly battlefield. Partly in response to changing attitudes about the nature of teaching and partly to ensure that male students maintained their full-time status, grades rose rapidly”. Then there seemed to be a lull in grade inflation until the 1980’s when grades began to rise again. “A new ethos had developed among college leaders. Students were no longer thought of as acolytes searching for knowledge. Instead they were customers” (Rojstaczer & Healy, 2010).

Note. Reprinted from Grade Inflation at American Colleges & Universities, by Rojstaczer, S.

“Two of the more frequently cited sources of grade inflation are faculty status and faculty evaluations” Hall (2011 p.146). Professors at some institutions are dependent on good evaluations from students. If the evaluations are not favorable and grades are low, then the teacher becomes suspect. “Simply stated, the higher the course grade, the happier the student, and the higher the ratings on the faculty evaluations completed by those students” Hall (2011). Motivating the student becomes an issue when the common grade is A. I found support that it becomes extremely difficult for professors to grade honestly because it can be viewed as a sign of poor quality education by the professor, his ratings go down and consequently enrollment in the institutions in future years will suffer.

In an article by Stroebe (2016), he discusses grading leniency encouraged by universities. Evidence is presented that the positive association between student grades and their evaluation of teaching reflects a bias rather than teaching effectiveness (p. 800). This cyclic process has only resulted in more problems. Poor student performance in subsequent courses tend to become apparent. Stroebe, a professor in the department of social and organizational psychology, University of Groningen, the Netherlands deliberates the notion that grading leniency or grade inflation is likely to demotivate students. He presents that students overestimate the amount they learn based on the grade they receive.

Institutions are at fault here as well and may be the one of the biggest proponents to perpetuating the vicious circle. As Hall (2012) explains in her article, “institutional interests also tend to have a significant impact on the prevalence of grade inflation in higher education. With more and more cuts to educational funding, many colleges and universities find themselves struggling to balance their budgets. Students who are happy with their grades are students who are much more likely to remain enrolled – thereby filling classroom seats and paying tuition fees (p. 147).

An issue that has revealed itself in my research is academic entitlement. “The attitude of many of the students today is that they have the right since they are the procurers.” (Hall, 2012 p.148). Thought provoking questions are asked by researchers as to the reasons of academic entitlement. As Greenberger, Lessard, Chen & Farruggia (2008) ask, “What are the circumstances that foster the behavior and attitudes of academic self-entitlement: i.e., expectations of high rewards for modest effort, expectations of special consideration and accommodation by teachers when it comes to grades, and impatience and anger when their expectations and perceived needs are not met?” (p. 1194).

- Rebuttal against grade inflation

Then there are those with opposing viewpoints that grade inflation is nonexistent. As Kohn (2002) states, “Even where grades are higher now as compared with then, that does not constitute proof that they are inflated. The burden rests with critics to demonstrate that those higher grades are undeserved, and one can cite any number of alternative explanations. Maybe students are turning in better assignments. Maybe instructors used to be too stingy with their marks and have become more reasonable. Maybe the concept of assessment itself has evolved, so that today it is more a means for allowing students to demonstrate what they know rather than for sorting them or “catching them out” (p. B8)

My rebuttal is that over the years attitudes have changed not only of the students, the professors and the institutions. Institutions are not just interested in being the best in providing education, they are not interested in the education business, they are interested in the business of education. Simply put how to make the most money. Professors are interested in keeping their jobs by keeping institutions happy with them. If they give poor grades institutions will think that their teaching ability is poor and students, since they are paying for their education, feel entitled to get good grades or they may give their instructor an unfavorable evaluation.

My interview was with a young physician who went to undergraduate school in 2001 then on to medical school, a residency program and an internship. She is currently a practicing physician in a large group practice. One of my reasons for the choice of interviewee is that in the line graph illustrated previously she falls in the time when A is the most popular grade given nationwide. I formulated my line of questions only to be side railed by the very first question; When you were in college, were you aware of grade inflation practices? Her answer was no. Well, I continued, there are quite a few articles written about grade inflation and how prevalent it has become. It has been steadily increasing over the last twenty years. Have you notice that your grades were inflated? She indignantly said, “absolutely not! I worked my butt off for every grade I got!” the conversation continued as I strove to gain some glimmer of grade inflation recognition. Have you noticed any fellow students getting A’s that did not put in an A effort? The answer was no – all the students I was with were hard working and deserved the grades they received.

After the unexpected denial or unawareness of grade inflation could my interviewee fit into the category of entitlement? I decided that it was a case of a hard-working student with drive, motivation and determination to receive the grades that she deserved. She grew up in a time of entitlement, and yes, she does exhibit some of those qualities but she works hard to this day. She may have grown up in the age of entitlement but she is a child of achievement. I would know since she is my daughter.

Solution

Hall (2012), Argues that in the fight against grade inflation what is lacking are the basic principles of instructional design. There is no “framework” in place in institutions for measures to prevent grade inflating propensities and actions. Anyone who investigates the sources of grade inflation will ultimately find themselves pointed in the direction of the students themselves. “The attitude of many of the students today is that they have the right since they are the procurers.” (Hall, 2012 p.148)

My experience with attending Chamberlain College for Nursing is that the courses are set up to allow the professors to grade honestly. The grading rubric is beneficial to the student who now knows exactly what is expected of him or her. It makes it a more objective approach to grading. As Kelly (2017) describes, “Here are three reasons why I find rubrics truly effective. First, rubrics save time because I can simply look at your rubric and mark off points. Second, rubrics keep me honest, even when I’ve had a horrible day …. I feel much more objective as I sit before my mountain of papers. More important than these two reasons, however, is that when I have created a rubric beforehand and shown it to my students I get better quality work. They know what I want. They can also see right away where they lost points” (p. 1)

Benefits

I agree with Hall in her analysis of grade inflation. I can see that there are many facets that are all contributing to the problem. Solving one issue will not resolve the problem. Grade Inflating practices are fundamentally wrong. It involves a faculty member to award a grade that is higher than earned. Although it is recognized as being an issue, the inappropriate conduct continues. Hall not only describes the various causes and the rationale why grade inflation continues, but she offers a framework that consists of a different approach to combating the problem with specific objectives, instruction and assessment. It sounds very much like the grading rubric. According to Stevens and Levi (2005), “At its most basic, a rubric is a scoring tool that lays out the specific expectations for an assignment. Rubrics divide an assignment into its component parts and provide a detailed description of what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable levels of performance for each of those parts” (p.3)

Conclusion

In conclusion, with instructors lowering their grading standards, “A” has become the most ordinary grade on college campuses. It’s like buying a dozen eggs with medium, large, extra-large and jumbo all mixed in one carton. With no true evaluation of students’ performance, you don’t know what you’re getting. Students have a sense of entitlement that parents and the environment we live in have fostered over time. Students expect an A with minimal effort. This can be demotivating and discouraging for students who truly give it their all. When there are no guidelines or enforced regulation of grades, the grades given in higher education will have less and less meaning. It’s time to stop giving trophies just for participation.

References

Ad Hoc Committee on Grade Inflation. Final Report of the Ad Hoc Committee Task Force on Grade Inflation. American University, Washington, DC. (October, 10th, 2016)..

Arnold, R. A. (2004). Way That Grades are Set is a Mark Against Professors. Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles.

Carter, M. J., Lara, P. Y. (2016). Grade Inflation in Higher Education: Is the End in Sight? Academic Questions, 29(3), 346-353. Doi:10.1007/s12129-016-9569-5

Caruth, D., Caruth, G. (2013, January). Grade Inflation: an issue for higher education. Turkish Journal of Distance Education. v.14, n. 1, p. 102-110. ISSN: ISSN-1302-6488.

Fauer, J., Lopez, L. (2009, October). Grade Inflation: too much talk too little action. American Journal of Business Education. v.2, n.7.

Greenberger, E., Lessard, J., Chen, C., Farruggia, S. (2008). Self-Entitled college students: contributions of personality, parenting, and motivational factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. (April 4th, 2008), 37:1193-1204. DOI 10.1007/s10964-008-9284-9.

Hall, R. A. (2012). A neglected reply to grade inflation in higher education. Global Education Journal, 2012(3), 144-165.

Kelly, M. (2017). Creating and Using Rubrics: Make Your Life Easier with Rubrics. About Education. (Updated February 03, 2017). http://712educators.about.com/cs/rubrics/a/rubrics.htm

Kohn, A. (2002). The dangerous myth of grade inflation. The Chronicle of Higher Education. November 8th, 2002. 49(11).

Rojstaczer S., Healy C. (2016). Where A is ordinary: The evolution of American college and university grading. 1940-2009. Teachers College Record, ID Number: 15928.

Rojstaczer, S. (2016). Grade Inflation at American Colleges and Universities. www.GradeInflation.com. (March 29, 2016).

Rojstaczer, S. (2003). Where all Grades are Above Average. The Washington Post. January 28, 2003. A21.

Stevens, D., Levi, A. (2005). Introduction to Rubrics: An Assessment Tool to Save Grading Time, Convey Effective Feedback and Promote Student Learning. Stylus Publishing, LLC. Sterling, Virginia.

Stroebe, W. (2016). Why Good Teaching Evaluations May Reward Bad Teaching. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(6), p. 800-816. DOI:

Summary, R., Weber, W. (2012). Grade Inflation or Productivity Growth? An Analysis of Changing Grade Distributions at a Regional University. Journal of Productivity Analysis 38.95-107.