Transitioning from a Linear to a Circular Economy

Prepare a critical review evaluating the challenges of transitioning from a linear to a circular economy. 2000 words (24th March)

- Introduction

The linear model of consumption will need to adjust or be replaced in the near future due to rising population, decreasing resources (i.e. metals, materials), and water limits. The current linear economic system is unsustainable but the concept of circular economy may supply the means to allow for sustainability by improving efficient use of material and energy.

From policies and frameworks driven on a macro scale by local governments to optimisation of process lines and waste reduction on a micro scale gives more social and sustainable aspects to our current way of resource use. We can use examples throughout the world of a shift in the utilisation of resources in an overall effect of achieving the ultimate goal of zero waste and impact to the environment.

- What is Linear Economy?

Linear economies assume the world’s resources are unlimited. The linear model’s primary objective is to the economy, with no regard for ecological and social impacts. It takes waste from the production process and contaminates the environment and is based on the principle, ‘take, make, consume, discard’ and everlasting availability of resources. (Drljaca, 2015) This was due to a historically cheap and plentiful amount of resources being available leading to companies focusing on supplying the customer. This has disregarded the environmental impact and lacked incentives to minimise waste from its production to its end of life.

Currently there is more than 11 billion tons of global waste globally and only 25% is recycled. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015)

- Circular Economy

Circular economy focuses on the sustainable exploitation of resources but also acts to increase the social responsibility. It ‘aims to decouple prosperity from resource consumption’ by ensuring a closed loop process which depends on the extraction of virgin resources. (Sauve, Bernard & Sloan, 2016) The concept allows waste to be put through the production process again and thereafter only a small amount of waste that is unable to be recycled is disposed into the environmental harmlessly. This will reduce our dependency for new resources, allow future generations to meet their needs, and promote sustainability.

Due to China’s resource supply and environmental problems they have utilised the circular economy model on a national level many years ago allocating three distinctive levels micro, meso, and macro:

- The micro level aims to reduce waste and optimise materials for cleaner production within an individual company.

- The meso level collaborates between industries to utilise the by-product of one another which is facilitated by China’s governmental directives.

- The circular economy at a macro level is integrated with societal and stakeholder interests which is on a similar level to sustainable development. (Sauve, Bernard & Sloan, 2016)

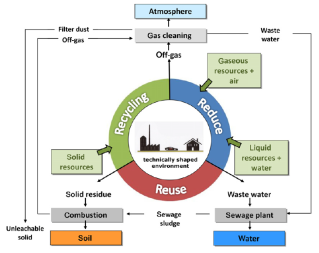

Figure 3.1: Overview of the circular economy concept. (Reh, 2013)

The circular economy model aims to replace the linear economy model by extending the usefulness of the product via several methods:

- Building a product which has a higher quality and more durable targeting the consumers who are able to pay a premium.

- Refurbishing a product

- Trade back your product to the market for a price

- Upgrade the product to add new features

- Refilling a component in the product where the rest of the functions are still in quality.

- Repairing a broken product (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015)

Having a society that promotes circular economy may increase competition worldwide. (Drljaca, 2015)

- Policies

The transition from a linear to circular economy has been happening for many years and is seen from the laws, policies, and frameworks given below in numerous countries around the world. The methodology changes from country to country as an example according to Tukker (2015) China promotes a top-down national political objective while the EU, Japan and USA use bottom-up environmental and waste management policies.

|

Country |

Circular economy strategy |

|

UK |

The House of Commons suggested in 2014 that the circular economy should be stimulated by taxation reforms. This would reward reuse and give more funding for companies promoting material recovery. They could prohibit companies using non-recyclable components where other alternatives exist. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015) |

|

Denmark |

The ‘Denmark without waste’ strategy focuses on better exploiting the resource by reducing the environmental impact and improving recycling, e.g. household waste recycling. Funding is given for improvements in waste separation and treatment facilities. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015) |

|

Scotland |

The ‘Safeguarding Scotland’s Resources’ initiative is aims to reduce material use through replacing material with reused/ recyclable substitutes and making sure that virgin resources are efficiently and productively used. |

|

China |

Several regions using the ‘Circular Economy Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China’ have set up funds aiming at the circular development and developments of science. The law also pushes for collaboration among several industries to re-use each other’s waste to benefit their own process. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015) |

|

Singapore |

The ‘Singapore Packaging Agreement (SPA)’ joint initiative by the private sector, nongovernmental organisations, and government which dramatically reduces the packaging waste in Singapore. This has saved USD 35 million over a 5-year period. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015) |

|

The Republic of Croatia |

The ‘Act on Sustainable Waste Management’ manages waste at its source by putting the cost of waste to the producer. Disposal must not threaten future generations. (Drljaca, 2015) |

- The drivers for the transition from a linear to a circular economy

The transition towards a circular economy is dependent on politics, culture, society, the economy, and technology limitations. This transition can be implemented from the top-down or bottom-up. The top-down process as an example has international and national policies delegated to companies and their operations and supply chains. The bottom-up process starts at the product level hoping to simulate ideas at a more disaggregated level of analysis up to the higher level systems. The top-down process should be used to enhance bottom-up initiatives. The aim is to identify areas where we can reduce virgin resources usage, carbon emissions, and waste production by collaborating between supply chains and stakeholders e.g. Local Authorities. (Genovese et al., 2017)

- Economics

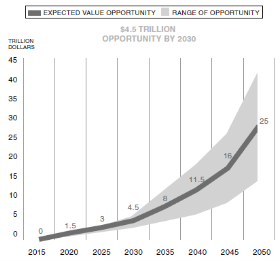

By 2030 the linear growth model will be unable to supply the growing demand for resources. The most likely model by Lacy & Rutqvist (2015) shows a USD 4.5 trillion loss by 2030 increasing to USD 25 trillion by 2050. If the circular economy replaces the current linear model it could potentially release USD 4.5 trillion in additional economic output by 2030 as shown in Figure 5.1.1.

Figure 5.1.1: Potential savings from a circular opportunity. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015)

However, according to Drljaca (2015), the circular advantage hopes to give a competitive edge leading to improvement of resource utilisation which could decrease material exploitation by 17-24% until 2030 with savings of ~EUR 630 billion per year which totals USD 10.3 trillion from 2015-2030 (1 EUR = 1.0867 USD 2015 average, Pound Sterling (2016)).

In either case the huge potential savings from using the circular advantage could persuade governments to drive the change.

- Fair competition between linear and circular economy

Current regulations give linear economy an unfair advantage over circular economy by making it more financially attractive by increased profits through expanding resource use. A shift of taxation from labour to resources would see this shift in bias. Companies are encouraged to extract new resources instead of investing in people and processes to achieve a higher productivity of resources already in use. Currently the Europe labour tax totals 52% of all tax revenues while <0.3% is given to natural resources. Reducing labour taxes and increasing the tax on raw resource use would give incentives for companies to employ talent leading to innovation within that area. (Lacy & Rutqvist, 2015)

Other taxes could include landfill tax, energy recovery tax, and reducing the VAT on a more circular advantage product. An increase in cost of the product that incorporates the cost of environmental impact would help manufacturers to minimise the impact to keep pricing competitive.

- Product-service systems (PSS)

In a product-oriented business model companies focus on the increase in products sold to maximise profits however in a PSS model companies are paid by offering a service and the product and consumable is the cost factor. This leads to the companies being incentivised to prolong the life of the product which could be done by using more robust materials or re-using parts to the end of the product’s life.

Renting, leasing, and sharing reduces the impact on the environmental per product manufactured however leased products will tend to be used without care leading to reduced longevity of the product and will be returned to the manufacturer more frequently compared to the traditional manner.

Due to labour intensity, PSS increases the cost to manufacture the product and dependent on the speed of innovations for certain technological industries the re-use of components may be deemed uneconomic due to no demand.

PSS can contribute to resource -efficiency and a circular economy but does not change the incentive to maximise the product sales. (Tukker, 2015)

-

Circular Economy Challenges

- Entropy

The circular economy assumes the planet is a closed system with the amount of resources being depleted equalling the amount of waste generated. This principle follows the Laws of Thermodynamics however in practice the circular flow of exchange starts with low entropy from the environment and ends with high entropy waste polluting the environment. (Genovese et al., 2017)

Sauve, Bernard & Sloan (2016) further emphasises this with an added social impact of, what is socially more desirable investing in a new infrastructure to recycle raw material to limit waste or exploit additional raw materials at cheaper cost to use today to build a school? At some point the cost to refine the material will exceed the benefit to the environment.

- Processes

According to Sauve, Bernard & Sloan (2016), in many cases certain processes in the value chains are non-existent leading to products that are in the queue for recycling often dis-regarded as companies who seek profit are not ready to use waste as the raw material for new manufacturing. Some experts see the implementation of the circular economy model for sustainable development on current linear economy model productions as an automatic failure.

It is difficult to achieve a profit using circular economy as support is sometimes unavailable through policies, national eco-industrial parks (EIPs) initiatives, environmental legislative framework, and economic taxes and subsidies for development. (Ghisellini, Cialani & Ulgiati, 2016)

- Economics & Fair Competition

The complexity and early understanding of circular economy will require experts from many sectors to achieve the economic incentives that would ensure the post-consumption products are re-integrated upstream within manufacturing. It is more expensive to manufacture a durable long lasting product than an equivalent quick and disposable version. This is based on the fact that the public pays for the cost of disposal to the environment. In order to make circular economy more feasible requires integration of the cost of disposal into the price paid by the customer. (Sauve, Bernard & Sloan, 2016)

There needs to be internalisation of full environmental costs implemented using certain governmental legislation (e.g. taxes) to ensure reverse flow of the products post-economy. This is therefore dependent on governmental intervention which is dictated by political-economic issues which in turn will slow down circular economy opportunities. (Sauve, Bernard & Sloan, 2016)

- Geographic Feasibility

It may be unfeasible to use recycling, reuse and/or recovery as an option within certain geologies as they may not be appropriate in some instances based on green chemistry and technologies available e.g. prevention maybe a better option. (Tukker, 2015)

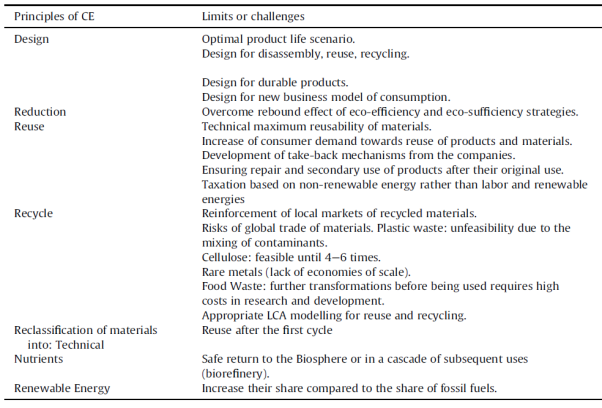

More examples can be seen in Table A1.

-

Case studies

- TATA Steel

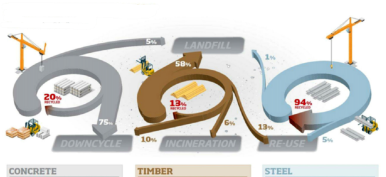

Currently concrete, timber, and steel have huge differences in their life cycle flows within the demolishing industry of buildings as seen in Figure 7.1.1. According to Reh (2013), achieving complete re-use and recycling remains impossible with today’s technology so maximum recovery of the most valuable resource remains the first priority. The integration of different materials combined with depreciation requires a more involved investigation of the recovery plan which becomes very complex.

Figure 7.1.1: Life cycle of a demolished building (Reh, 2013)

Blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) is the most common steel process however with shortage of metallurgy coke, high CO2 emissions, high by-product of slag, and dust from blast furnace gas cleaning is not considered environmental friendly. An alternative being the new electric arc furnace which is more energy efficient and reduces the CO2 emissions but high capital investments remain the limitation. (Reh, 2013)

- Toyota Motor Cooperation

By optimising the sorting of dust in Toyota’s automobile shredder pants Toyota were able to successfully treat 100% of the residue of 15,000 cars per month into valuable materials. High value electrical energy is transferred to several process steps to decrease the entropy of mixing during production. This improvement in technology has an exponential impact on the car industry with an estimated 1 billion cars in the world. (Reh, 2013)

- Conclusion

The transition to a circular economy has many challenges and obstacles in the near future. As shown, many countries are placing high emphasis on the legislation and development of circular economy as they see a requirement to adjust on a macro sustainable level. If the transition is increased this could potentially unlock several trillions of dollars over the many years to come. In order for this to work a combination of strategies at every level is required to allow each stakeholder to be a benefit to the global transition.

Appendix A

Table A1: Further examples of challenges with circular economy (Ghisellini, Cialani, & Ulgiati, 2016)

References

BRIEN, H. G. (2015a) Circular Economy. [Online] Available from https://kenniskaarten.hetgroenebrein.nl/en/kenniskaart/circular-economy/ [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

BRIEN, H. G. (2015b) The 10 Big Questions for the Circular Economy. [Online] Available from http://hetgroenebrein.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/10-Big-Questions-for-the-Circular-Economy-INFOGRAPHIC.pdf [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

DRLJACA, M. (2015) The Transition from Linear to Circular Economy (Concept of Efficient Waste Management). In Association for Quality and Standardization of Serbia. VrnjaÄka Banja, 2015. p. 35-44. Available from http://www.kvalitet.org.rs/images/phocadownload/the%20transition%20linear%20in%20circular%20economy%20miroslav%20drljaa.pdf [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2015) Our Mission is to Accelerate the Transition to a Circular Economy. [Online] Available from https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

GENOVESE, A. et al. (2017) Sustainable supply chain management and the transition towards

a circular economy: Evidence and some applications. Omega. [Online] 66. p. 344-357. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0305048315001322/1-s2.0-S0305048315001322-main.pdf?_tid=74c6de02-fa10-11e6-aa77-00000aacb35f&acdnat=1487886106_74b304b3dc5437e17e5fe519fa8c0812 [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

GEORGE, D. A. R., Lin, B. C. & Chen, Y. (2015) A circular economy model of economic growth. Environmental Modelling & Software. [Online] 73. p. 60-63. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1364815215300050/1-s2.0-S1364815215300050-main.pdf?_tid=0bc1df60-fa10-11e6-8c30-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1487885930_37488d1ce4f1739084fd69489fc8a1a7 [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

GHISELLINI, P., CIALANI, C. & ULGIATI, S. (2016) A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner Production. [Online] 114. p. 11-32. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0959652615012287/1-s2.0-S0959652615012287-main.pdf?_tid=1b6a27e6-fa11-11e6-b2c6-00000aab0f6b&acdnat=1487886386_e13f933c344129238b699b40c81c696b [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

LACY, P. & RUTQVIST, J. (2015) Waste to Wealth: the circular economy advantage. UK, Hampshire: Macmillan Publishers Limited.

POUND STERLING (2016) Historical Rates for the EUR/USD currency conversion on 31 December 2015 (31/12/2015). Available from: https://www.poundsterlinglive.com/best-exchange-rates/euro-to-us-dollar-exchange-rate-on-2015-12-31. (Accessed: 19th March 2017)

RAUPACH, M. R. et al. (2007) Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO2 emissions. PNAS. [Online] 104. (24). p. 10288 -10293. Available from https://uhi.blackboard.com/bbcswebdav/pid-621274-dt-content-rid-5673934_1/courses/UF811998/PNAS-2007-Raupach-10288-93.pdf [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

REH, L. (2013) Process engineering in circular economy. Particuology. [Online] 11. p. 119-133. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1674200113000023/1-s2.0-S1674200113000023-main.pdf?_tid=f6b7e250-fa0e-11e6-9938-00000aacb360&acdnat=1487885465_0117d7df5a14a5ca6f24c03ae761e2d5 [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

SAUVE, S., BERNARD, S. & SLOAN, P. (2016) Environmental sciences, sustainable development and circular economy: Alternative concepts for trans-disciplinary research. Environmental Development. [Online] 17. p. 48-56. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S2211464515300099/1-s2.0-S2211464515300099-main.pdf?_tid=c0687f78-fa10-11e6-bdc2-00000aacb35e&acdnat=1487886233_c2050df04694fc30b490f4e8486dee8a [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

SKEA, J. & NISHIOKA, S. (2008) Policies and practices for a low-carbon society. Climate Policy. [Online] 8. p. S5-S16. Available from https://uhi.blackboard.com/bbcswebdav/pid-621272-dt-content-rid-5632275_1/courses/UF811998/Policies%20and%20practices%20for%20a%20low-carbon%20society-1.pdf [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

SU, B. et al. (2013) A review of the circular economy in China: moving from rhetoric

to implementation. Journal of Cleaner Production. [Online] 42. p. 215-227. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0959652612006117/1-s2.0-S0959652612006117-main.pdf?_tid=5aa9aef6-fa0f-11e6-9009-00000aacb362&acdnat=1487885633_e486ac7b90cff16cd44ec5b72b405a9a [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

TUKKER, A. (2015) Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy – a review. Journal of Cleaner Production. [Online] 97. p. 76-91. Available from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0959652613008135/1-s2.0-S0959652613008135-main.pdf?_tid=b1c99494-fa0f-11e6-bafc-00000aacb362&acdnat=1487885779_1dbb3b632024a09a87307a26dc6caf65 [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

YADUVANSHI, N. R., MYANA, R. & KRISHNAMURTHY, S. (2016) Circular Economy for Sustainable Development in India. Indian Journal of Science and Technology. [Online] 9 (46/ December). p. 1-9. Available from http://www.indjst.org/index.php/indjst/article/view/107325/76142 [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]

ZINK, T. & Geyer, R. (2017) Circular Economy Rebound. Journal of Industrial Ecology. [Online] 00 (0). p. 1-10. Available from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.eor.uhi.ac.uk/doi/10.1111/jiec.12545/epdf [Accessed: 23rd February 2017]