UK Guidelines for Eye Screening

DOES THE UK CURRENTLY SCREEN THE POPULATION FOR APPROPRIATE EYE CONDITIONS?

WHAT IS SCREENING?

Screening is a way of identifying those individuals who are at a higher risk of developing a certain health problem; this allows them to have appropriate early treatment and information in order to prevent further deterioration. There are many different screening programmes which are offered by the NHS, for example, Screening for newborn babies, Diabetic Eye screening, Cervical Screening, Bowel Cancer Screening etc. (Nhs.uk, 2017). The screening process uses tests which can be applied to a large number of people and is an initial examination which requires further investigation and follow up. There are many different types of screening, for example, Mass screening (e.g. chest x-rays for TB), Multiple screening (e.g. annual health check), Targeted screening for those at a higher risk of developing specific diseases e.g. battery workers would be at a greater risk of developing cancer or problems with their nervous system (Anon,2017) and lastly Opportunistic screening. Opportunistic screening relates to identifying those at a higher risk to see whether they actually have signs of a condition as we carry out the pre-screening process/sight test, for example, we tend to check the pressures and fields of the people (maybe should write ‘of patients’ over..) over the age of 40 in order to check for any signs of glaucoma, however, this cannot be classified as screening as it is ‘opportunistic’ (Anon, 2017). Within this essay I will mainly be discussing Diabetic Eye Screening and Amblyopia Screening, I will be analysing how well these relate and correspond to the criteria set by the WHO guidelines for screening, how the screening programmes could be improved and what screening programmes are out in the world which could benefit us if brought within the UK. A full discussion of the classifications of diabetes or amblyopia is beyond the scope of this essay.

10 CRITERIA 1968 WHO GUIDELINES FOR SCREENING

There are 10 main criteria/principles that a screening programme should meet in order to be an effective, practical and appropriate way of screening within the UK. These were brought about in 1968 by Wilson and Jungner (WHO) (Patient.info, 2017). Further down in this essay how well Diabetic Eye Screening and Amblyopia screening match the 10 criteria will be discussed, table 1.1 summarises the findings and a potential condition that we could screen for in order to enhance appropriateness of screening for eye conditions within the UK (Gp-training.net, 2017):

(TABLE 1.1)

|

1968 WHO GUIDELINES |

DIABETIC EYE SCREENING |

AMBLYOPIA SCREENING |

AMD |

|

|

1. |

The condition being screened for should be an important health problem |

 |

? |

 |

|

2. |

The natural history of the condition should be well understood. |

 |

 |

 |

|

3. |

There should be a detectable early stage |

 |

 |

 |

|

4. |

Treatment at an early stage should be of more benefit than at a later stage. |

 |

 |

 |

|

5. |

A suitable test should be advised for the early stage. |

 |

 |

? |

|

6. |

The test should be acceptable. |

 |

 |

 |

|

7. |

Intervals for repeating the test should be determined. |

 |

 |

? |

|

8. |

Adequate health service provision should be made for the extra clinical workload resulting from screening. |

 |

 |

? |

|

9. |

The risks, both physical and psychological, should be less than the benefits. |

 |

 |

 |

|

10. |

The costs should be balanced against the benefits |

 |

 |

 |

DIABETIC EYE SCREENING

It is estimated that within the UK, 4.5 million people have diabetes and around 1.1 million people have yet to be diagnosed (Anon, 2017). It is essential that we screen individuals who have diabetes as the development of Diabetic Retinopathy is one of the major complications of diabetes and early diagnosis can lead to appropriate and effective treatment (Hamid et al, 2016). This Diabetic Eye Screening (DES) is separate from a sight test and is to be carried out annually. If a woman is pregnant she will be offered additional tests as the development of gestational diabetes is common i.e. diabetes which only occurs during pregnancy, however, if the mother already has diabetes she also has a higher risk of Diabetic Retinopathy development (Nhs.uk, 2017).

1.1 Attendance at Diabetic Screenings

Forster et al. (2013), evaluated whether patients who did not attend their DES were at a greater risk of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy (STDR). They carried out a longitudinal cohort study over 3 years (2008-2011) in which diabetic residents were invited for the screening. Forster et al found that 5.6% of the patients who did not attend in 1 year for their DES developed STDR. 2.6% patients who previously had ‘no retinopathy at their first screen’ had developed STDR when they did not attend in 1 year and 5.7% of participants developed STDR when they did not attend for 2 consecutive years. With participants who previously had ‘mild non-proliferative retinopathy’ at their first screen, 16.8% of these developed STDR when they did not attend for their DES in 1 year and 17% developed STDR when they did not attend for 2 years. (is this in your own words if not results should be quoted just to avoid plagerism)The results found for referable maculopathy also followed the same pattern but the affected participants were smaller. This longitudinal study has its benefits as a large number of data can be collected however as it is over the period of 3 years, there is a risk of individuals dropping out of the study and therefore data for one year may not be comparable to the data from the next year as there would be subject differences. The findings of this study suggest that there is importance for DES and it can be deemed as an appropriate eye condition to be screened for within the UK as it does allow early detection of diabetic referable retinopathy and the greater the time between the DES the greater the risk of the development of STDR. However whether we need to screen individuals annually could be further discussed (Forster et al, 2013).

1.2 Improvements for DES Screenings

To improve how we currently screen within the UK for appropriate eye conditions we could consider, increasing the time between the DES by making them biennial i.e. every 2 years. Forster et al found that participants had a 10.84 times higher chance of referable retinopathy if they had not attended their screening for 2 consecutive years, compared to those participants who were screened for every year.(I think should be kept in but change to own words if not already.) He found that for those patients who attended every 2 years had no significant increased risk of referable retinopathy compared to those who attended annually. A number of benefits can be seen from increasing the time between the screenings. Firstly this would mean that less DES would be carried out, this frees up time and space; in practices, this allows more time for regular sight tests and at the hospital, it allows more space for other important appointments. Reducing the number of DES also means that fewer professionals would be required for these screenings; this would cut down the costs made by the NHS. Some could argue that this could lead to a cut down in the number of optometrists who specialise in the DES, however, this would allow the current professionals specialised in the DES or the ones that do carry out the training to become more skilled and have more focused knowledge on DES.

Scanlon et al. (2013), found that those who were not screened promptly after being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes had a raised rate of detection of referable diabetic retinopathy. The study didn’t show whether those who were screened at a later date had a more severe form of diabetic retinopathy or whether it was anything to do with patient compliance but it did indicate that screening patients within the Quality standards set by NICE were more beneficial for the patients (Scanlon, Aldington, and Stratton, 2013). This supports that the UK does currently screen appropriately for eye conditions such as Diabetes and in a timely manner, as the earlier we screen a patient after being diagnosed with diabetes, the less of a chance for the development of severe/unnoticed diabetic retinopathy, as the development of DR is most prominent within the first two decades of developing the disease (Fong et al, 2017). In the UK, patient’s information once being diagnosed with diabetes is transferred via their GP to the Diabetic Eye Screening Services as soon as they are diagnosed, this allows appropriate treatment and screening for the patient immediately. We cannot solely rely on this study as it does not include any facts or figures regarding how raised the risk is for referable DR if a DES is not carried out every year. Therefore to improve screening within the UK; following Forster et al study, we could increase the time between the screenings i.e. make it biennial. The Health Improvement and Analytical Team of the Department of Health found that it would be more cost effective if the screening intervals were increased from one year to another when carrying out a cost-utility assessment for those who have low risk of development of Diabetic Retinopathy; these being defined as those who have been graded to have no background retinopathy in either eye, therefore one way of improving the screening in the UK could be by increasing the intervals between the DES (James, 2000).

Currently, within the UK, Diabetic eye screening is offered to individuals who are 12 years and older. They are contacted by their local Diabetic Eye Screening service informing the patient as regards to what practices are available for them to attend for their screening i.e. a local opticians, hospital or clinic. Hamid et al. (2016) carried out a retrospective analysis of 143 patients aged between 7 and 12 in order to see whether DES should be carried out on children under the age 12. 73 of these patients were below the age of 12 and the other 70 were 12 years of age. He found that ‘both these groups had a similar prevalence of background diabetic retinopathy (early stage of diabetic retinopathy) and none had STDR’. From Hamid et al results, it can be seen that there would be no benefit to starting the DR at an earlier age as the same results are found in both groups, therefore supporting the current English protocol of starting DES at 12 years of age. A DES test within the UK is fairly easy to carry out and requires the patient to be dilated; once the patient is dilated they are unable to drive for roughly 4-6hours in order for their pupils to return to normal.(this could be referenced from somewhere see if you can find from article or anything on how its done then reference that) This could be considered as some inconvenience to the patient as they may be required to take a day off work or prevent doing specific tasks that day however as the DES is carried out annually it is only a matter of a few hours, which could easily be rearranged or time off work can be taken. The risks of the drops are very low; a few symptoms could be experienced for example pain, discomfort, redness of the eye, blurry vision and haloes around lights which can lead to Angle Closure Glaucoma. ACG can be treated and the benefit of carrying out the DES is much greater and outweighs the risks.

1.3 DES Screening In India

Currently, in India, in addition to the current Diabetic eye screening that is being carried out in practices, they are also going to be trialing (think it needs double ll m grammerly says you’ve spelt it the American way) Mobile DES services. This will benefit patients in several ways; firstly those who are not able to leave their homes are able to get screening and treatment readily. Furthermore, not all clinics have the appropriate equipment required in order to carry out DES, therefore, with the Mobile DES services patients are able to still get the adequate healthcare required. This is yet to be trailed therefore the success rates are unpredictable. If in the future, this helped patients get the adequate screening and healthcare required in India, then this could also be trialled within the UK in order for improving eye screening for appropriate conditions (Kalra et al, 2016).

AMBLYOPIC SCREENING

The common vision defects in children aged around 4-5years tend to include amblyopia, strabismus (squint) and refractive error (short or long sighted). (is this referenced from tailor et al like the next sentence, if not then needs a reference) An estimation of the prevalence of amblyopia in the UK varies between 2% and 5% (Tailor et al, 2016). Amblyopia is well understood and occurs when the nerve pathway from one eye to the brain does not develop adequately during childhood (Medlineplus.gov, 2017). Individuals are said to have an amblyopic eye when their vision is worse than 6/9 Snellen or 0.2 LogMar in the affected eye.(reference needed)Â The UK National Screening Committee along with the recommendations from the Health for All Children agreed that orthoptic-led services should offer to screen for visual impairments for children aged 4-5 years (Legacyscreening.phe.org.uk, 2017). If the amblyopia is treated while the visual system is plastic i.e. still developing within the critical period (first seven to eight years of life), then this can be an effective way of restoring normal vision. Untreated amblyopia can have a negative impact on an individual’s adult life; within the UK it was found that only 35% (36 out of 102) of people were able to continue their employment after losing the vision in their non-amblyopic eye (Rahi, 2002).

2.1 Testing

The tests for amblyopia can include monocular visual acuity testing, plus or minus assessment of the extra-ocular muscles, colour vision testing, and binocular status (Stewart et al, 2007). The screening process can vary depending on the density of the amblyopia and age of the patient i.e. this would alter the treatment required. Patching seems to be the most common treatment for amblyopia and is seen to have improvements in vision if it is carried out adequately i.e. compliance is required. Stewart et al. (2007), researched the benefits of patching in which they found 40 children who were patched for 6 hours had an improvement in 0.21 to 0.31 log units of vision compared with another 40 children who were patched for 12 hours had a 0.24 log unit improvement. This supports the idea that patching can be carried out for fewer hours and still produce a similar enhancement in vision. However, when compliance was monitored there wasn’t much of a difference between the hours, for the patients prescribed 6 hours they tended to vary between 3.7 to 4.7 hours and the 12-hour patching children varied between 5.1 and 7.3 hours (Stewart et al, 2007). (maybe some more critical analysis of this study, I know you’ve got sample size and randomisation but if you can may add some more) These results suggest that Amblyopic patients can be patched for fewer hours and still have the same improvement in vision, however, compliance is necessary.

Following on from this study when a randomised trial was carried out in order to see the effectiveness of Atropine and patching as a treatment of Amblyopia, it was found that visual acuity in the amblyopic eye improved for both, therefore supporting patching and atropine as adequate treatments for Amblyopia (Stewart et al, 2007). In this study equal, sample sizes were used and patients were allocated randomly, this allows the removal of subject bias and allows comparisons between the subjects and therefore more reliable results can be obtained. Furthermore, it was found that the younger the child, the less the occlusion in hours that would be required, therefore, the earlier we test the child for amblyopia the better the treatment (Stewart et al, 2007).

2.2 Problems with Patching

Referring back to the 1968 guidelines in Table 1.1, patching may not be deemed as an acceptable form of treatment. When a randomised trial was carried out on 4 year old and 5 year old children it was found that they had experienced short term distress and were more upset when having to wear a patch alongside glasses than wearing glasses alone (Williams et al, 2006). Children also reported having been bullied whilst wearing a patch causing emotional problems which in turn led to long term adverse consequences. Williams et al. (2006) carried out a prospective study, in order to test their hypothesis by comparing children who had been screened preschool and required a patch and those who had not. 95% confidence limits were calculated and it was found that the risk of being bullied was the same for those who wore glasses and had been screened preschool and not. However, when comparing the preschool and school children and the rates of bullying whilst wearing the patch it was found that there was almost a 50% reduction in the group of children who had been screened preschool (Williams et al, 2006). From these results, it can be concluded that pre-school vision screening would reduce down the bullying experienced by the children whilst wearing the patch therefore in order to improve screening within the UK we could potentially screen the children earlier to prevent the psychological stress that the child has to experience. During this study, the data was collected via an interview with the children. Children’s responses could vary depending on who was interviewing the child, the gender of the child (girls would be more(not would-they may be more likely to) likely to admit to being bullied) and other factors too(what other factors-either state them or leave it at the last point); therefore these results could not fully represent whether the child had experienced bullying and this factor should be taken into account when viewing the results.

2.3 Screening for Amblyopia within Japan

Currently, outside of the UK, there are different screening processes which occur. The screening process for Amblyopia within Japan starts at the age of one and a half years old and then the children are later screened at 3 years of age by paediatricians. In The School Health Law based in Japan, the Visual Acuities of children ranging from 6 years old to 12 years old are taken by the school teachers then the children are screened by Ophthalmologists to screen for the eye diseases and amblyopia (Matsuo and Matsuo, 2005). Several studies over the years have been collected in order to compare the number of strabismus patients identified in different countries. Comparing these different studies it can be found that overall there were fewer children in Japan who developed strabismus, only 1.28% of the sample. Within the UK when a similar study was carried out it was found that 4.3% of the total number of children screened developed strabismus, this being much larger than those who developed it within Japan (Matsuo and Matsuo, 2005). This variation in results may suggest that the screening process in Japan is a lot more thorough compared to the UK and as children in Japan are screened for fairly early on in life, they are continuously kept an eye on, this could increase the detection of the early developments of Amblyopia and therefore appropriate treatment is also given fairly early on. (but is it screened more thoroughly in japan only because japanease children are more prone to amblyopia- is the prevalence of amblyopia higher in japan-if so then that might be why they screen earlier-find out) However, we cannot solely base the development of strabismus on the way we screen the children as there could be other factors as well. One way in which we could modify screening within the UK could be by screening children at an earlier age and more often as well; this would allow early detection of Amblyopia and therefore early appropriate treatment, reducing the number of strabismic individuals. Tailor et al. (2016) identified that a large area of controversy when discussing screening for Amblyopia is that it is currently not clear whether screening children earlier is associated with better outcomes and also whether it is more cost efficient or not, however it is widely agreed that starting screening for amblyopia at the age of 4 to 5 years old it seems to be clinically effective and also cost efficient at the moment therefore further research needs to be carried out in order to see whether we should move the screening for Amblyopia to an early stage or not (Tailor et al, 2016).

IMPROVING SCREENING WITHIN THE UK – AMD

Within the UK to improve screening we could also screen for further conditions such as for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. AMD is an important health problem and accounts for 8.7% of all legal blindness worldwide. The development of Choroidal Neovascularisation (CNV) is the main cause of severe vision loss which leads to the development of ‘Wet’ or ‘Exudative’ form of AMD (Schwartz and Loewenstein, 2015). AMD development is pretty well understood by professionals and it can lead to changes in your central vision and also have an impact on the quality of an individual’s life. Patients with AMD have reported more difficulties when performing tasks such as reading, leisure activities, shopping etc. (Hassell, 2006). There is currently no treatment for the dry form of AMD, whereas wet AMD is currently being treated using intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents which lead to an improvement in 30-40% patient’s visual acuity (Schwartz and Loewenstein, 2015). In Table 1.1 an extra column has been added in order to compare how well AMD screening would relate to the WHO criteria if it was to be screened for within the UK.

3.1 Techniques

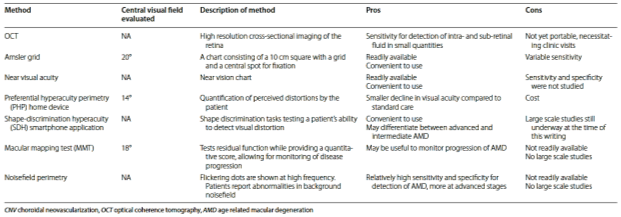

It has been found that the treatment of AMD at an earlier stage is of more benefit than at a later stage. Treatment of CNV within 1 month was found to have a greater gain in visual acuity than treatment which was given after this timeframe (Schwartz and Loewenstein, 2015). If AMD patients were left untreated for a year they would lose two or three lines of vision on average therefore the earlier the detection of AMD the more beneficial (Anon, 2017). The screening process could involve an Optical Coherence tomography (OCT) and a fluorescein angiography (FA) alongside clinical examinations, for example, Amsler charts, Nosefield Perimetry, Near Visual Acuity etc. In Table 1.2 these examination techniques have been presented in a table and the Pros and Cons of each technique can be seen.

TABLE 1.2 (Schwartz and Loewenstein Int J Retin Vitr (2015) 1:20)

TABLE 1.2 (Schwartz and Loewenstein Int J Retin Vitr (2015) 1:20)

3.2 Screening Criteria

If screening programs were to be carried out within the UK for AMD, we would need to consider a few factors. Firstly, at what age would we start to screen individuals for AMD and how often these screenings would take place would need to be considered(-don’t need highlighted bit). AMD is most common in individuals who are over the age of 65, however, can be seen in some in their forties or fifties, not only is it affected by age but smoking, family history, UV exposure and diet can also be risk factors for the development of AMD (Rnib.org.uk, 2017). There could be a few different criteria in which individuals would qualify for the screening process of AMD, a few of these criteria could potentially be:

- Any individual over the age of 60 years old.

- Any individual over the age of 50 years old with a family history of AMD.

- Any individual who experiences one or more of the following symptoms: difficulty reading with spectacles, vision not as clear as previously or if experiencing straight lines becoming wavy or distorted (Rnib.org.uk, 2017).

Once this screening process is carried out the recall period could vary depending on the patients’ health, family history, and lifestyle, this could vary from yearly up to a 5 year recall period for those that are normal; have no family history of AMD and good lifestyle. If an individual is diagnosed with Dry AMD then these screening processes would occur much more regularly in order to monitor the health of the eyes and to detect Wet AMD at an early stage. A benefit for the proposition of screening for AMD within the UK is that it would lead to more jobs and professionals to be specialised within AMD.

3.3 Time Efficient

There are a few flaws with screening for AMD. If OCT images were not clear enough patients may need to be dilated, this would mean that the patient would not be able to drive for approximately four to six hours, which could result in the patients having to take a morning/afternoon or a day off work.(maybe you can find a study where people are asked about what they don’t like in dilation and it might be they don’t like taking time off-then can reference that here) If all the above techniques mentioned in Table 1.2 were to be carried in the screening process for AMD, this in itself would be quite a lengthy process and would also require time to be taken off unless it was carried out on an individual’s none working day. Screening for AMD would involve Fluorescein Angiography this may not be accepted by some patients as it is an invasive process and requires fluorescent dye to be injected into their bloodstream. Therefore suitable techniques would be required in which the patient would consent to if screening for AMD was to be carried out within the UK. Furthermore, currently within the UK, only half the adult population (48%) have heard of AMD therefore screening for AMD within the UK could be a challenge as public awareness of this disease is very limited therefore the public may be unable to recognize any symptoms or changes in their vision being related to AMD (VISION 2020, 2017). The development of CNV can be very rapid and therefore patients may remain asymptomatic or mechanisms within the brain could lead to overcome the noticeable change in their vision during the early stages of this disease, therefore, it would be difficult to screen the patient in their early stages of AMD (Rnib.org.uk, 2017). Further information should be given to individuals in which they are informed of what symptoms to look out for and also what to do in these instances.

3.4 Costs & Practicality

Currently within the UK if patients require a private OCT scan this can vary in price ranging from thirty-five pounds (C4 SightCare) to eighty-nine pounds (Leightons Opticians). Free OCT scans may be carried out in hospitals settings or learning institutes, for example, The University of Manchester (Gteye.net, 2017). If we were to routinely carry out OCT scans for everyone as a technique during AMD screening then this can be very costly if funded by the NHS, in addition, if this was to be carried out privately then patients may not be willing to pay that much for the AMD screening process and therefore the success rates for screening for AMD within the UK would be less as patients wouldn’t attend the screening. Furthermore, other techniques such as fluorescein angiography can be costly to be carried out for example if patients require this to be carried out privately they may end up paying up to £103 (Anon, 2017). Another issue arising with the potential to screen for AMD would be regarding the practicality of the screening process; the equipment and machinery are fairly large and would require the practices to have adequate space in order to carry out these screenings. In addition, the equipment itself is very expensive and companies may not want to invest in such equipment if there turnover isn’t worth it. In order to overcome this, we could potentially just carry out AMD screening within a hospital setting however it would still depend on the amount of space available to carry out these processes. Overall screening for AMD is quite a lengthy process and if it was to be carried out within the UK it would require a lot of work in order to make the screening process affordable and time efficient too.

CONCLUSION

Overall, within the UK we currently do screen for appropriate eye conditions these including Diabetic Eye Screening and Amblyopia. We could further increase this by screening for conditions such as Age-Related Macular Degeneration, as it is a very serious eye condition and early detection and treatment is beneficial. However, there are quite a few different factors which need to be considered if screening for AMD was to be carried out as mentioned above. Also, there are currently limited studies on AMD and therefore further research should focus on AMD and the benefits of continually screening the patient. Currently, as screening is being carried out for Amblyopia, this could be an eye condition that doesn’t necessarily need screening for. A Cochrane review(do you need to reference which one) found that there is currently not enough evidence to determine whether the number of children with amblyopia was reduced due to the screening programs or not. The main reason for this was that definition of Amblyopia is widely debatable and there is a lack of universally accepted definitions of amblyopia, which makes the data collected from different studies difficult to compare. However, it is much easier to leave a screening process in place rather than to remove it as a whole as further complications can arise and screening for this is somewhat beneficial. From the discussion within this literature, it can be seen that we do currently screen for appropriate eye conditions within the UK.

REFERENCES

- Nhs.uk. (2017). NHS screening – Live Well – NHS Choices. [online] Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Screening/Pages/screening.aspx#what-is.

- Anon, (2017). [online] Available at: https://www.med.uottawa.ca/sim/data/Screening_e.htm. [Accessed 5 Feb. 2017].

- http://www.hsa.ie/eng/Publications_and_Forms/Publications/Chemical_and_Hazardous_Substances/Safety_with_Lead_at_Work.pdf [Accessed 9 Feb. 2017].

- Patient.info. (2017). Screening Programmes in the UK. Find Screening Centres. [online] Available at: http://patient.info/doctor/screening-programmes-in-the-uk [Accessed 5 Feb. 2017].

- Gp-training.net. (2017). Screening criteria. [online] Available at: http://www.gp-training.net/training/tutorials/management/audit/screen.htm [Accessed 5 Feb. 2017].

- Scanlon, P., Aldington, S. and Stratton, I. (2013). Delay in diabetic retinopathy screening increases the rate of detection of referable diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic Medicine, 31(4), 439-442.

- Forster, A., Forbes, A., Dodhia, H., Connor, C., Du Chemin, A., Sivaprasad, S., Mann, S. and Gulliford, M. (2013). Non-attendance at diabetic eye screening and risk of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia, 56(10), 2187-2193.

- Hamid, A., Wharton, H., Mills, A., Gibson, J., Clarke, M. and Dodson, P. (2016). Diagnosis of retinopathy in children younger than 12 years of age: implications for the diabetic eye screening guidelines in the UK. Eye, 30(7), 949-951.

- Legacyscreening.phe.org.uk. (2017). Vision Defects. [online] Available at: https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/vision-child [Accessed 13 Feb. 2017].

- Fong, D., Aiello, L., Gardner, T., King, G., Blankenship, G., Cavallerano, J., Ferris, F. and Klein, R. (2017). Diabetic Retinopathy.

- James, M. (2000). Cost effectiveness analysis of screening for sight threatening diabetic eye disease. BMJ, 320(7250), 1627-1631.

- Powell C, Hatt SR. Vision screening for amblyopia in childhood. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005020. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005020.pub2.

CHECK REF NOT CORRECT COCHRANE REVIEW)

- Rahi J S, Logan S, Timms C, Russell-Eggitt I, Taylor D. Risk, Causes and outcomes of visual impairment after loss of vision in the non-amblyopic eye: a population based study. The Lancet 2002;360(9333):597-602.

- Tailor, V., Bossi, M., Greenwood, J. and Dahlmann-Noor, A. (2016). Childhood amblyopia: current management and new trends. British Medical Bulletin, 119(1), 75-86.

- Stewart, C., Stephens, D., Fielder, A. and Moseley, M. (2007). Objectively monitored patching regimens for treatment of amblyopia: randomised trial. BMJ, 335(7622), 707-707.

- Medlineplus.gov. (2017). Amblyopia: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. [online] Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001014.htm [Accessed 24 Feb. 2017].

- Hassell, J. (2006). Impact of age related macular degeneration on quality of life. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 90(5), 593-596.

- Schwartz, R. and Loewenstein, A. (2015). Early detection of age related macular degeneration: current status. International Journal of Retina and Vitreous, 1(1).

- Gteye.net. (2017). Gordon Turner Optometrists – Cheam Opticians – Glaucoma Screening. [online] Available at: http://www.gteye.net/OCT_screening.html [Accessed 7 Mar. 2017].

- Anon, (2017). [online] Available at: http://www.torbayandsouthdevon.nhs.uk/uploads/23968.pdf [Accessed 7 Mar. 2017].

- Rnib.org.uk. (2017). Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) | RNIB | Supporting people with sight loss. [online] Available at: http://www.rnib.org.uk/eye-health-eye-conditions-z-eye-conditions/age-related-macular-degeneration-amd?gclid=CIeVhqf32NICFaEL0wodIVIGQQ [Accessed 15 Mar. 2017].

- Matsuo, T. and Matsuo, C. (2005). The Prevalence of Strabismus and Amblyopia in Japanese Elementary School Children. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 12(1), 31-36.

- Kalra, S., Unnikrishnan, A. and Tandon, N. (2016). Diabetic retinopathy care in India: An endocrinology perspective. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 20(7), 1.

- VISION 2020 UK. (2017). Lack of Awareness Risking Thousands of People’s Sight Each Year – VISION 2020 UK. [online] Available at: http://www.vision2020uk.org.uk/lack-of-awareness-risking-thousands-of-peoples-sight-each-year/ [Accessed 20 Mar. 2017].

- Williams, C. (2006). The timing of patching treatment and a child’s wellbeing. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 90(6), 670-671.